“I Kiss My Ghosts’ Sticky Foreheads.” Jane Wong on Poetic Ambivalence and Feeding on the Past

“Each day, I rub my eyes with poetry, bleary in foggy morning light.”

I message my friend Keith and bemoan the fact that I’m not psychic. That I’m not as powerful as my mother, that I can’t make things happen. Why didn’t her powers trickle down to me? No one wants Janewong.com (though someone did buy that domain so I couldn’t. Reveal yourself!). But Keith tells me: “Your poems are incantatory. You did inherit it.”

I sit with this generous message for a while. Maybe I wasn’t psychic in my regular life, but maybe poetry was the portal through which my powers came alive. In my first book, Overpour, there’s a poem toward the end called “Ceremony” where I envision the future:

This is what we were promised: another life. / Today, I run with a flare in my hand like a bouquet of exploding flowers. / Today, I will not be transparent.

I wrote this poem before leaving the Bad One, forcing a future I wanted, needed in order to survive. And isn’t this memoir a kind of flare? Didn’t I need to write that poem in order to leave?

In my second book, I don’t have a clear memory of writing the last poem, “After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly,” in which my ancestors speak directly to me and have a massive feast. I remember being at the Lettered Streets Coffeehouse in Bellingham with my colleagues and telling them I had to go into the other room and write a poem. I was compelled, pulled into an alternate dimension by all my limbs. The poem came out in two hours and I barely revised it. I moved through that day in a haunted haze.

Then I get mad at poetry. I get mad at myself. I feel disgusted by poetry and its lyricism. How dare I poetize death.

Have you ever co-written a poem with ghosts? What I can tell you: amid the chaos of the world around me, my ghosts have my back. I think about what they did and didn’t survive during the Great Leap Forward (also known as the Great Famine), a Maoist agricultural campaign that led to the death of an estimated 36 million people. I think about the acidity of starvation, the fields of bodies returning to earth. Did they fall in love during a time like that? Did they see me, a little restaurant baby with a severe bowl haircut, slicing bright scallions behind the counter? How long did it take for the flies to descend, to sip at grief?

Through poetry, they led me around the spinning table of their desires. Through poetry, they demanded a future cornucopia. They demanded durian, omelets, steak, bitter gourd, pizza, flip-flops, my soul. The last line of the poem reads: “Tell us, little girl, are you / hungry, awake, astonished enough?”

Wake up to your powers!

Each day, I rub my eyes with poetry, bleary in foggy morning light. I clear goopy line after goopy line out of their corners. It’s true. Poetry does make me feel powerful. Poetry’s magic does loosen the sinking weight of fear. Even when I’m not writing, I’m writing. Sitting still in the raging heat of the bathtub, I guzzle language like salt. Stirring a thickening pot of jook, I kiss my ghosts’ sticky foreheads. Then I get mad at poetry. I get mad at myself. I feel disgusted by poetry and its lyricism. How dare I poetize death. These were the real corpses of my family. These were real bruises on my neck. A man really did choke me. Real death, real vertigo, real addiction, real debt, real labor, real hunger. My father was really never going to call me. What if there’s nothing to say at all?

I return to Lucille Clifton often, one of my central literary loves. From her poem “why some people be mad at me sometimes”:

they ask me to remember

but they want me to remember

their memories

and i keep on remembering

mine.

I can’t deny the psychic power, ancestral power, poetry power that moves through these magnetic lines. Even in my shame, I feel Clifton’s words stir my fluids awake, frothing. I think about her insistence: “i keep on remembering / mine.” And how that determination to remember her memories angers people. I love how “mine” sits on its own line, cemented in self-knowledge. Even if poetry fails us, we need it to survive. From the end of her poem “won’t you celebrate with me”: “come celebrate / with me that everyday / something has tried to kill me / and has failed.”

There’s another video of my mother that I caught on my phone, a perfect pairing to JANE I’M PSYCHIC. She’s sitting in my aunt’s car and she says to the camera: “Don’t mess with me. Or you will become a frog.” I play this one on loop too, whenever I feel the pungent need for retribution. It makes me inextricably happy to watch it.

I send it to my brother in Jersey who texts back: LOLOL typical. She delights in the word “frog,” which sits in her throat like a paperweight. I love the combination of seriousness and humor in her voice, in her glimmering eyes. Like, really, don’t mess with her. The universe will become a croaking pond. Are you ready to feel the amphibious slick of your leg?

I wonder what Wongmom.com is afraid of. It almost seems like she’s not afraid of anything. But isn’t that impossible? To be fearless? I know this can’t be true. Everyone is afraid. I need to know, so that I don’t feel so alone in my fear. I type that in: “what are you afraid of, Mommy?”

______________________________

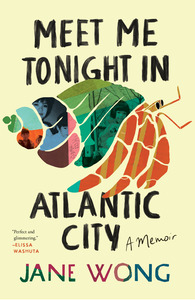

Excerpted from Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City by Jane Wong. Used with permission by Tin House. Copyright (c) 2023 Jane Wong.

Poem “why some people be mad at me sometimes” by Lucille Clifton from The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton 1965–2010. Used with permission, BOA Editions, 2012.

Jane Wong

Jane Wong is the author of How to Not Be Afraid of Everything, Overpour, and memoir, Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City. She holds an M.F.A. in Poetry from the University of Iowa and a Ph.D. in English from the University of Washington and is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Western Washington University. Her poems can be found in places such as Best American Nonrequired Reading 2019, Best American Poetry 2015, The New York Times, American Poetry Review, POETRY, The Kenyon Review, New England Review, and others. Her essays have appeared in places such as McSweeney's, Black Warrior Review, Ecotone, The Common, The Georgia Review, Shenandoah, and This is the Place: Women Writing About Home.