“I Have to Give a Lot to the Reader on Every Page.” A Conversation With Graphic Novelist Brecht Evens

The Author of The City of Belgium Talks to Tom Devlin

Brecht Evens and Tom Devlin spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a fall events initiative by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. Evens and Devlin have worked together since Evens sent a cold submission to D+Q that became his first book The Wrong Place. The driving force behind October’s conversation was the June release of Evens’s The City of Belgium, his fourth and most ambitious book.

The interview presented below offers the highlights of their lively, joke-filled conversation, which took place on Zoom, with Evens speaking from his studio in Paris, and Devlin from the Drawn & Quarterly office in Montreal.

*

Tom Devlin: In preparation for this, I pounded your four books in quick succession. I’ve read them so many times as we worked on them over the years, but what’s nice about doing the full reread is seeing different threads, getting a feel for how the artist views the world.

One of the things I noticed is that you seem to create a space and then let your characters loose in that space. They joke and chat and have digressive conversations. And eventually everything comes into sharp focus. You don’t seem in a rush, which is almost surprising given how detailed your painting is. Could you talk a bit about the idea of creating the space and letting the characters loose in it?

Brecht Evens: Partly the detail of the drawings might be a fear of wasting paper. We are cutting down trees for this. I have to give a lot to the reader on every page.

The books don’t start from a world or a space. Instead, some machinery inside the character gets me interested. And then quite quickly I start thinking of the space, but that’s the second phase. I try to use it as much as possible, try to use the space to tell the story, but the story itself always comes from something about a person, or an interaction between characters.

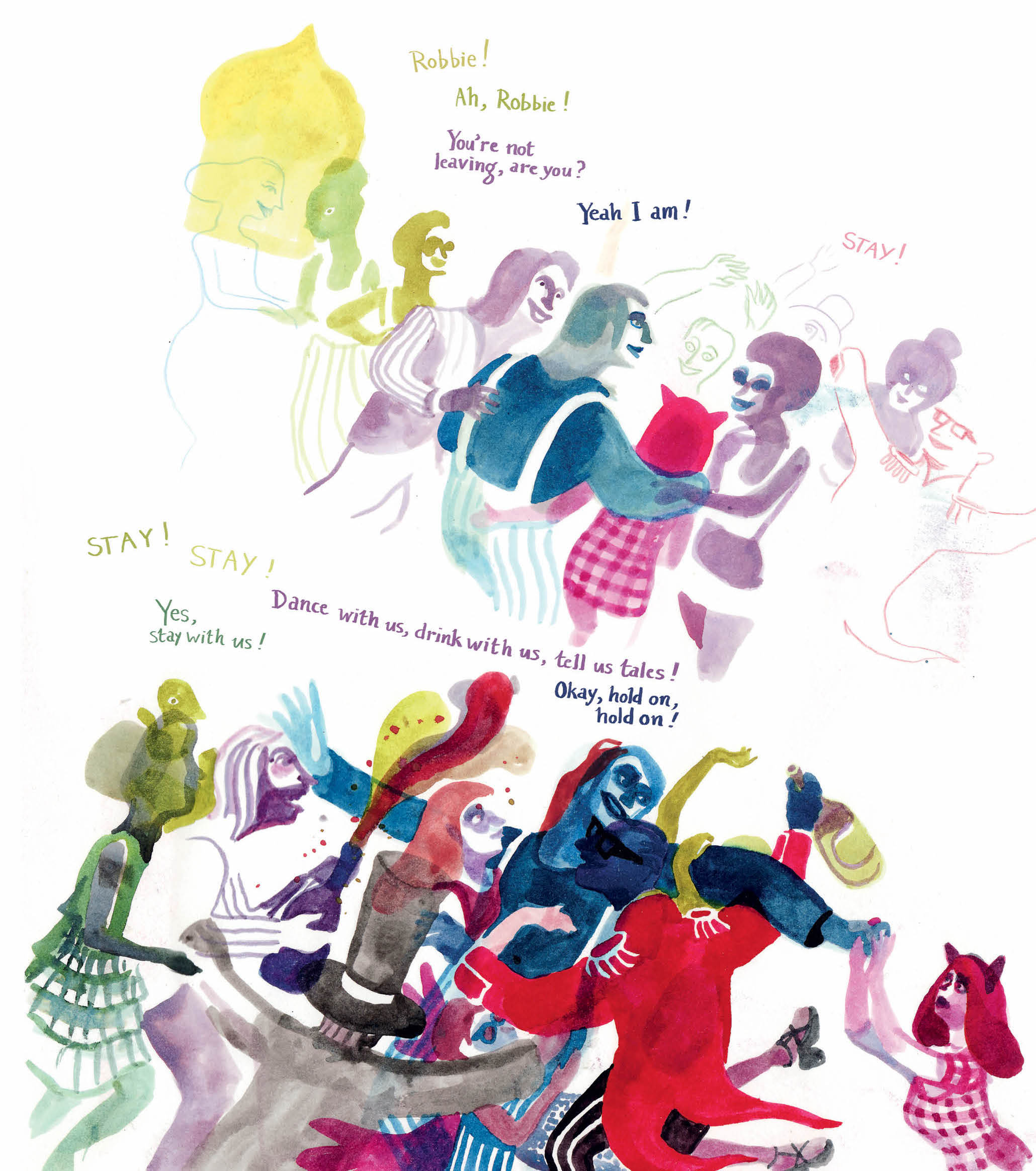

From “The Wrong Place.”

From “The Wrong Place.”

TD: One of the things that struck me is the similarity between your first book, The Wrong Place, and your most recent one, The City of Belgium, stylistically. I’m sure that you see tons of things that are different, but it’s clear you have the chops and you’re already drawing your characters in a loose, cartoony way. You’re using color in a thick blocky way. Each character is assigned a color to signify who’s speaking and interacting. So you have a lot of that in play already with The Wrong Place which you were working on in art school.

From “The City of Belgium” (L) and “The Wrong Place.”

From “The City of Belgium” (L) and “The Wrong Place.”

BE: The Wrong Place marked a huge jump for me graphically at around age 21 and because it started as a school project, I wasn’t yet thinking about saving paper. When you’re in school, the more drawings you have on the wall by the end of the year, the better. I had a very cavalier attitude toward wide space and that made the drawing sometimes more experimental. The other books are denser.

I’ve been exploring other stuff since then, not just trying to get twice as good at that thing I was doing, but more like enlarging the terrain, laterally getting better. So yes, there are a lot of the same kind of scenes in The City of Belgium, some party scenes and some scenes which I explicitly drew to be exactly like pages from The Wrong Place. And in some cases, the old drawings are better, grungier, jazzier, dirtier. Don’t worry, I think about that a lot. Am I losing things at the same time exploring new stuff, but trying to keep all the old furniture there too graphically?

TD: After The Wrong Place came The Making Of, which, at the time struck me as, “Brecht put out a comic that was a hit in Europe and has been published around the world. And now he’s going to festivals, so this book is about going to a festival.” What was the basic thought in creating that book?

BE: Artists, friends of mine, my classmates were also starting to go to festivals and one of them, Brecht Vandenbroucke, hilariously summarized a very, very amateur art festival, which was basically organized by boy scouts. Around the same time, I had a dream about doing some kind of beautiful incomprehensible project in a magical countryside. The meeting of those two, the sinister, beautiful, emotional feeling of the dream, and the funny anecdote Brecht told me, inspired a storyline to do with group dynamics.

I knew I had a book when I kept thinking of three steps that Peterson, the main character, goes through. He’s embarrassed and disgusted by the festival and then their love for art makes him want to believe, and then he starts to become a tyrant.

From “The Making Of.”

From “The Making Of.”

So once I got that character movement, I began drawing. And then as with the other books, I write something mostly inspired by things other people tell me. And I fill in the blanks with the autobio stuff, what I find in my closets. The Making Of has a lot of my hometown’s atmosphere: the backyards that you see from the train with a kid’s slide, a bird bath.

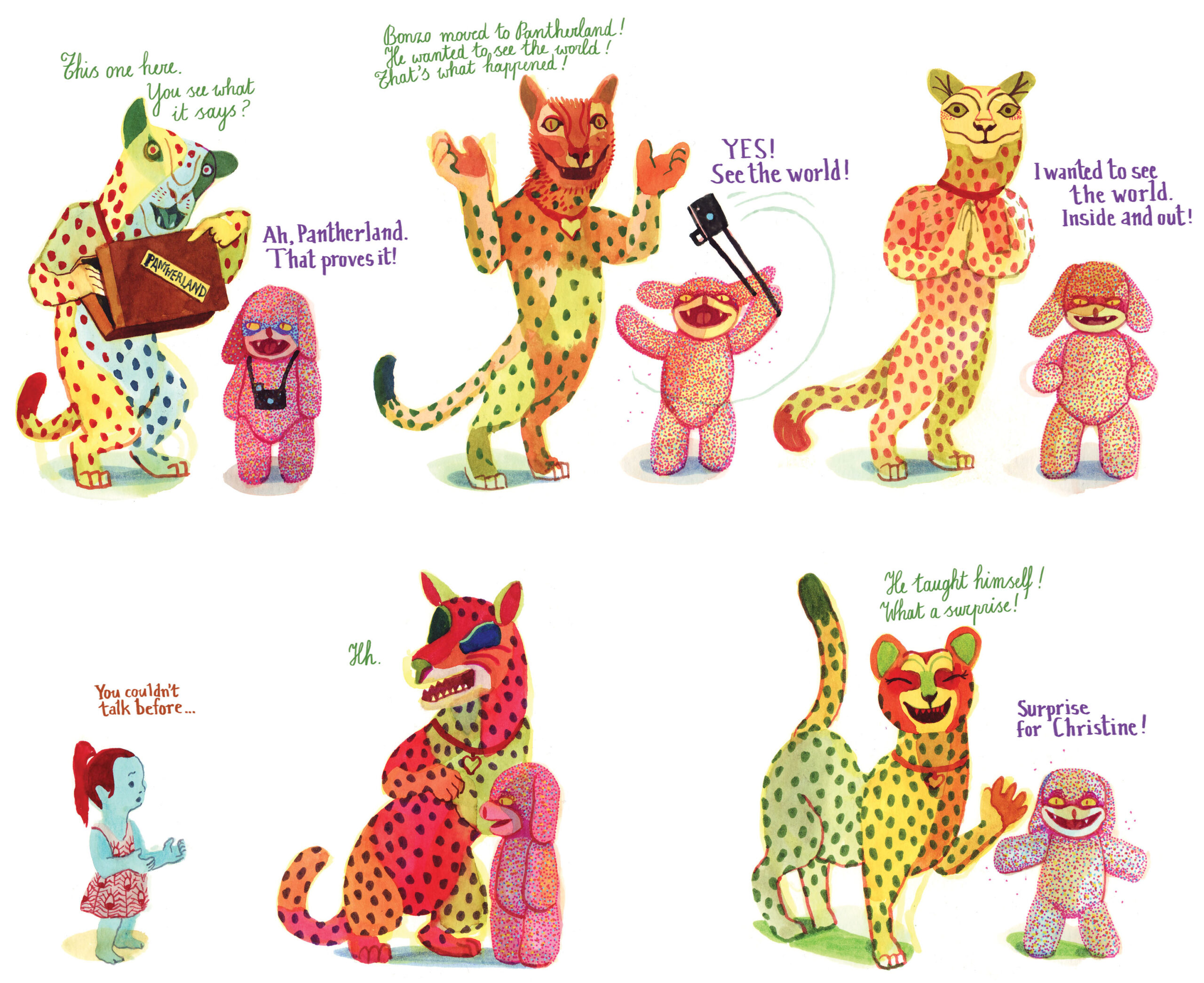

TD: The big shift happened with Panther. There’s no ‘Brecht’ character in the book. It seems wholly fantastic, a kind of dream state. And it’s also really dark, which the first two aren’t.

People have described it as an abuse story. But what I wanted to get to, is that you started to have mental health issues during Panther.

BE: Which is a stupid coincidence really. It’s very tempting to link my depression and Panther intellectually. In fact, the idea for Panther came just after The Wrong Place, but instead I started The Making Of.

I did some sketches for Panther, and thought, “No, this book is way too strange.” So when I finished The Making Of, I went back into the sketchbooks and thought, “Ah, this idea 100% exploits the possibilities of telling a story with drawings in the most simple way because one of the main characters himself is lying with his shape, and actually literally disappearing into the background.”

I didn’t set out to make a book about child abuse, but I’m not stupid, of course it is about that.

TD: I’m curious if you felt the confidence to kind of go dark and not make it ridiculous, I suppose. At this point after a couple of books under your belt, if you thought, “I want to explore things a little bit deeper.”

From “Panther.”

From “Panther.”

BE: Well, it’s definitely a deeper exploration of the medium and it pushes the reader’s buttons very perversely, efficiently.

The weird thing about Panther is that it’s also a very funny book. At the same time it’s funny, and sweet, and sort of desirable. And, of course, the darkest, most horrible thing possible. This pendulum is the strength of the book. These extremes are put together. Then as you mentioned, I fell into a depression.

So I will always have quite a complicated relationship with Panther, because I lost my means of making art during it. And when I was in this whole bipolar adventure, no one gave me a date for when I was going to be cured from my last bout of depression. So I thought, “I have to get back to doing my job. I might be like this forever.”

Also very strangely the book is done perfectly chronologically, which I almost never do. I started at page 1, 2, 3. It feels to me like in the first 80 pages I have all my artistic means, but I haven’t thought out an ending yet. I was doing it linearly.

And then the last 40 pages, I don’t have my means anymore. You can see it in how the characters are drawn. They are moving less smoothly, there’s a lot more wide space around them. Confidence leaves the author at that point, which if I’m thinking wistfully about the book might have been the only way to end it. There’s a sadness in the last chapter of the book. I don’t consider depression to be good for inspiration or art-making.

All my flamboyance, all my skill was taken from me. We did patch it up for the English translation. We gave it some more texture, and some more pages at the end.

TD: Let’s talk about The City of Belgium. It’s about the end of young adulthood. You’ve got to grow up and think about the world beyond tonight’s party. And the three main characters are all in a pretty big crisis. It remains pretty lighthearted overall considering that.

From “The City of Belgium.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

BE: One thing The City of Belgium has in common with The Wrong Place, apart from the partying and the city setting, is that both of them are Frankenstein books. They came from separate stories in my head, that I wove together. The Wrong Place was originally three short stories.

With City of Belgium my depression is over and I’m living in Paris. I’m looking around, open to hearing conversations and thinking about other people again, because one of the horrible things about depression is how egocentric a state it is: You’re obsessed with one little thing about yourself that you are turning, and turning, and turning over in your mind. The mind is no longer a place with several stairways and places to go. So when I woke up from my depression and lived in this huge, beautiful city, I wanted to make a kaleidoscopic ensemble city book again. But what kind of characters get me interested? Ones that are in crisis. Ones that are lying to themselves, or trying to escape something, or going through extreme states.

TD: A lot of people would have just focused on one of those characters, taken them through a night.

BE: It’s three books in one!

TD: But why did you decide on three? Did you just decide, I like this character, I like this character, and if I do a book on just this one person, then I don’t get to talk about these other people? It’s a big book as a result.

BE: Yeah, I wanted it to be a very generous world. A book to really take time with, and walk around in. But I didn’t build up to three characters from zero, it’s more like I was reducing from 12 main characters to three. Cutting the stories that seemed flatter, to end up with three important stories.

From “The City of Belgium.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

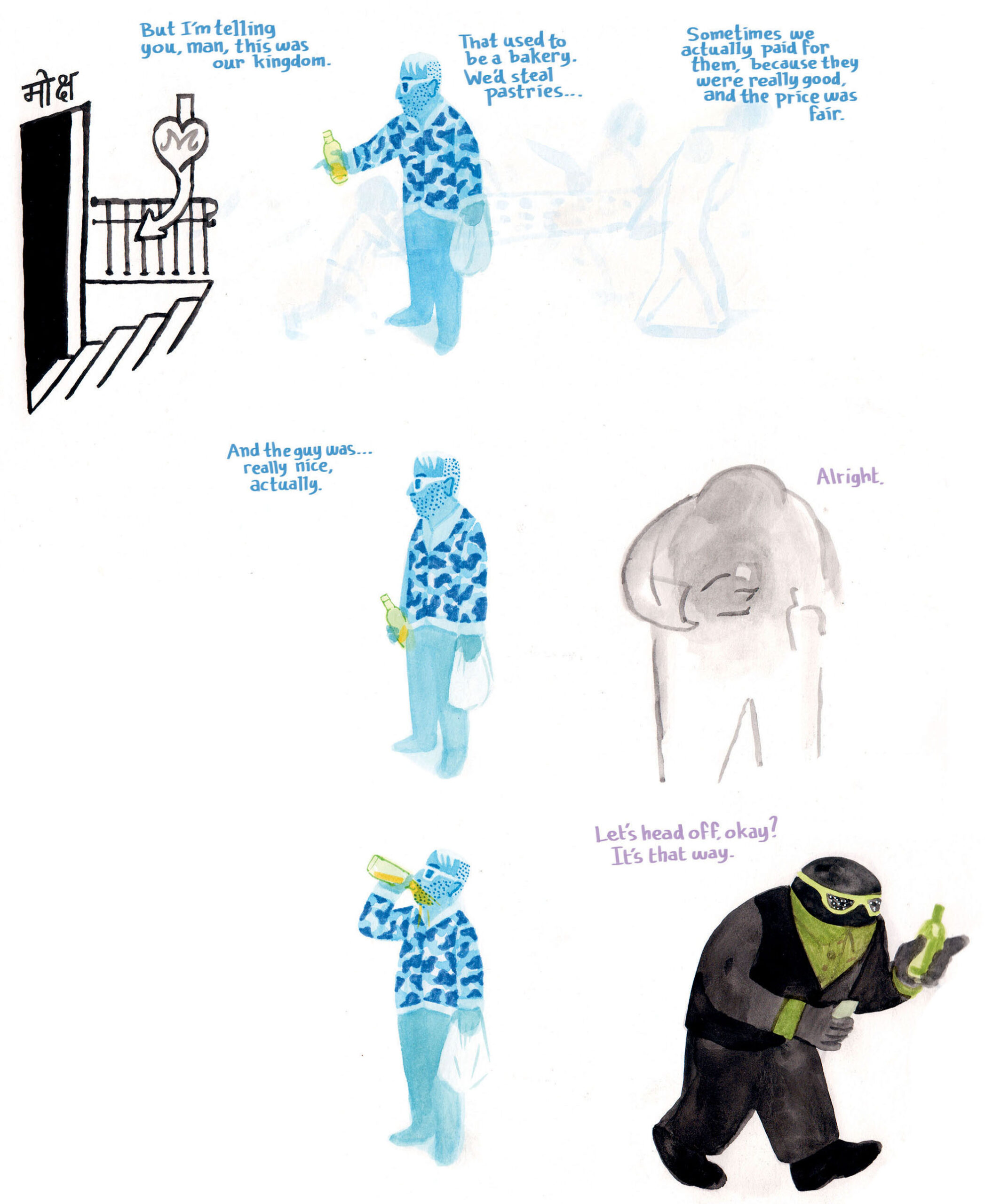

The story about Jona, the blue guy who is having his last evening before moving to Berlin, is inspired by a friend of mine. Well, someone we went out with a lot. He came from a really poor background, grew up with a lot of crime. And for him becoming a hipster—living the city life, owning certain clothes and objects—was a real aspiration.

Plus he really liked explaining his life to me. So I once did a friend interview with him for eight hours. Just asking, “How did you meet your girlfriend? How did that go?” He could talk for eight hours about himself easily. Then I lost my notes.

He had been in my notebooks for years before starting the book. Often the book starts by going through old notebooks, so you should always keep those.

TD: Are the notebooks mostly writing, like story ideas, or are they doodles?

BE: When I was a student they were much more visual, and now it’s mostly writing, and quick jotting down of ideas. Stories that are useless at the moment, but that become seeds later. Almost every time it’s been like this.

TD: The City of Belgium starts in this restaurant, and you give us the clamor in the restaurant that tails off, but we’re in that restaurant until Vic leaves. Vic leaves around page 240 or something.

So most of the first two thirds of the book take place in this restaurant. With a lot of overlapping. Rodolphe, I guess, leaves earliest.

BE: It’s 200 pages by the time everyone gets out of the restaurant.

TD: Yeah. He maybe leaves around 120 or something, and slowly everybody gets around to leaving.

Are you like, “Okay, I want the readers to get to know these characters. I’m going to go to this place, and they’re going to be clanking around for a while until you know who they are well enough. And then they get to leave.”?

You’ve stated that it’s much more plotty than that, that you’re not just completely improvising.

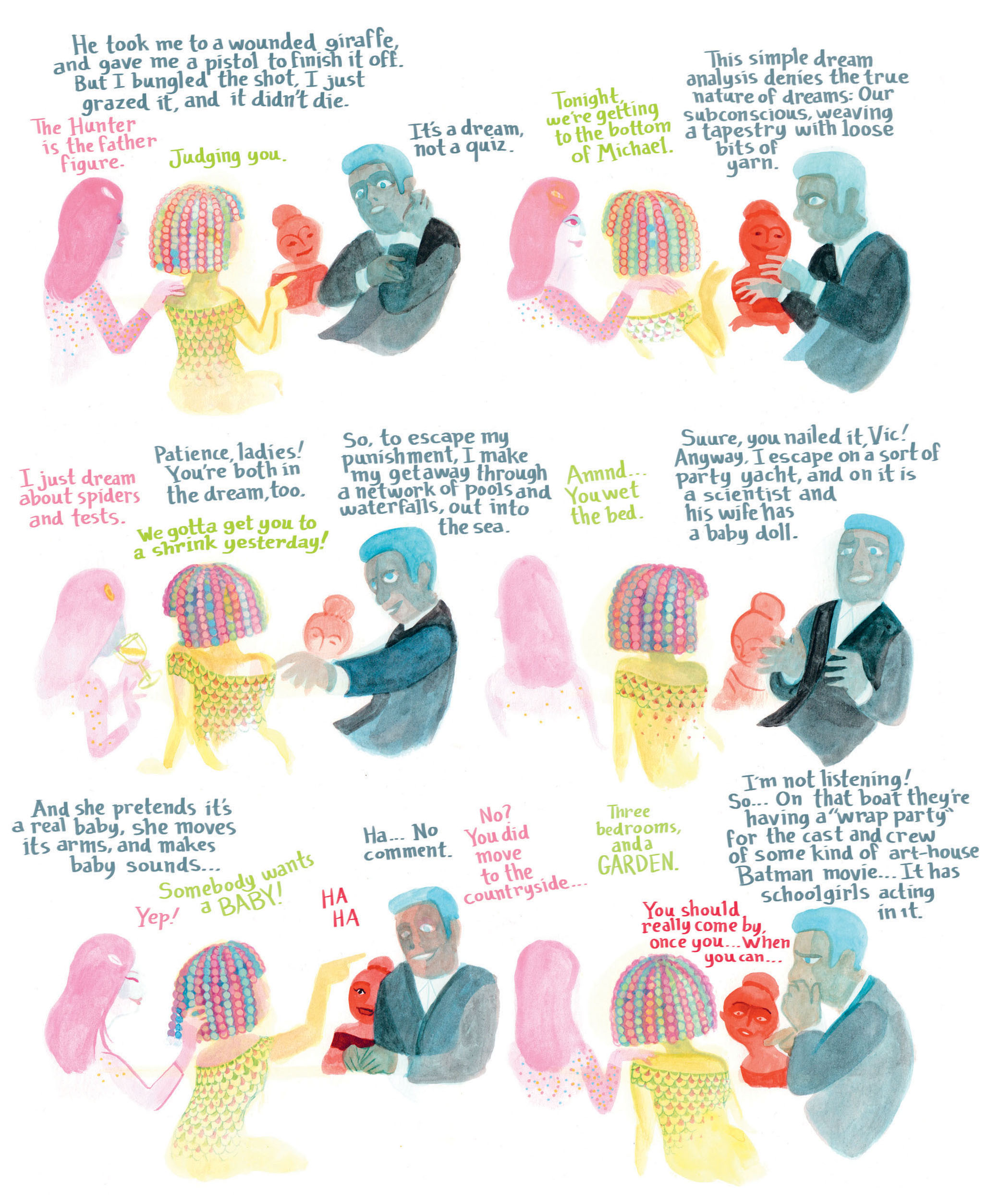

Also there are a few characters who very explicitly tell stories. The cab driver tells a version of the same story to each of the people who leave the party, each of our protagonists. And what’s great about those is that they’re almost always shaggy dog stories of different stripes. And also the cab driver loses the thread, or loses the ambition.

From “The City of Belgium.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

BE: He gets distracted!

TD: Always before we get to a satisfying place, too. It’s this ‘always testing’ the protagonist’s patience with this story, and then they get drawn in, and then the cab driver has kind of lost their ambition.

BE: He is making them up on the spot, he is improvising. The length of the story seems to be defined by how long the rides take.

So I wanted to write them like someone improvising them. These little nuggets of story are very plot driven, but in a shaggy dog way. The way I wrote these little vignettes is again a lot of notebooks. Or else abandoned storylines I might’ve considered making a book about, and those get rehashed to create a moment with this character more than telling something.

TD: More than telling a story about storytelling, was that part of it?

BE: It’s doing that. This is how it would sound if you go story, story, story, and then there was a sound outside, and I went out on the first night, and the second night, and the third night.

They’re fairytale structures, which worked fine.

From “The City of Belgium.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

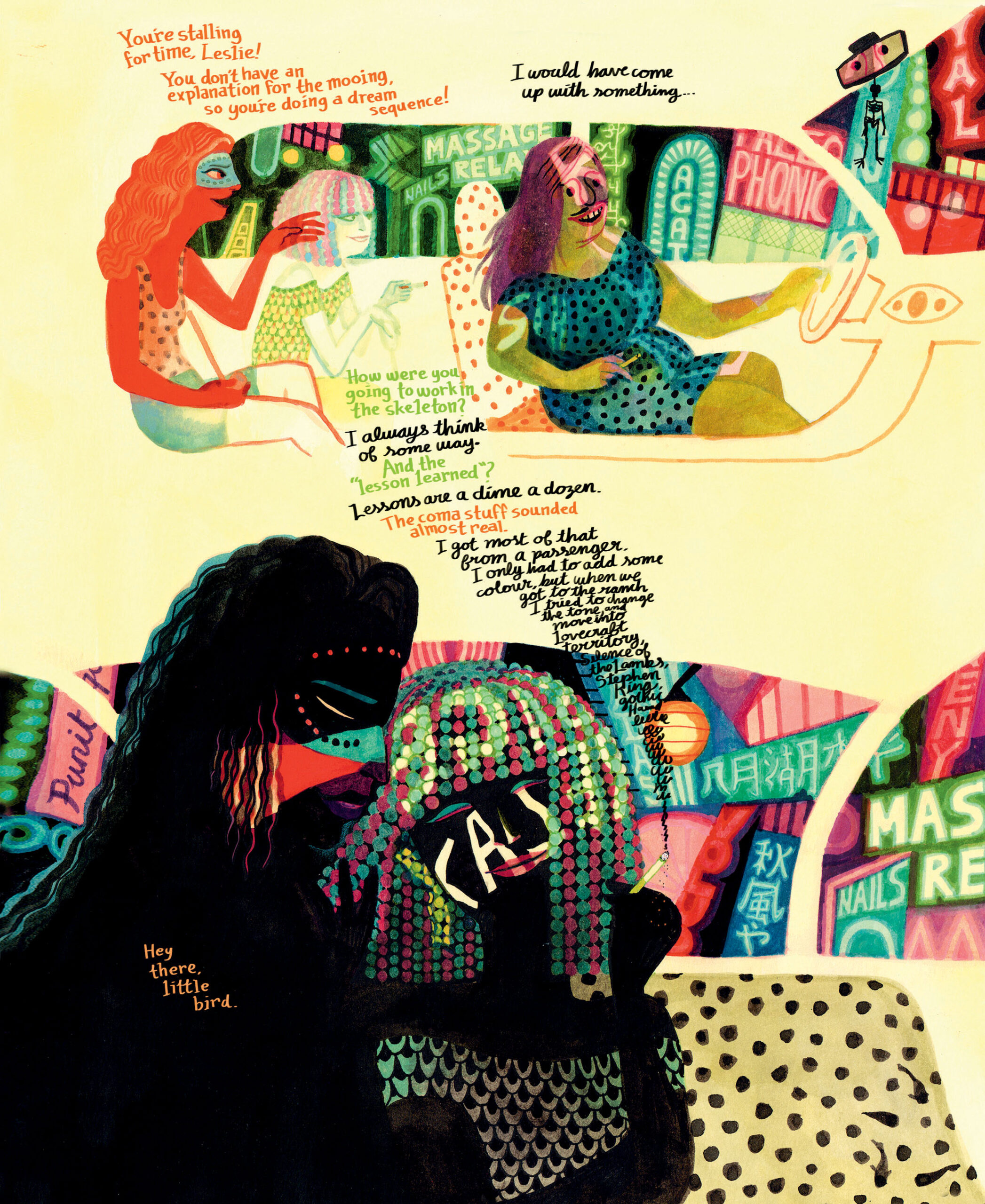

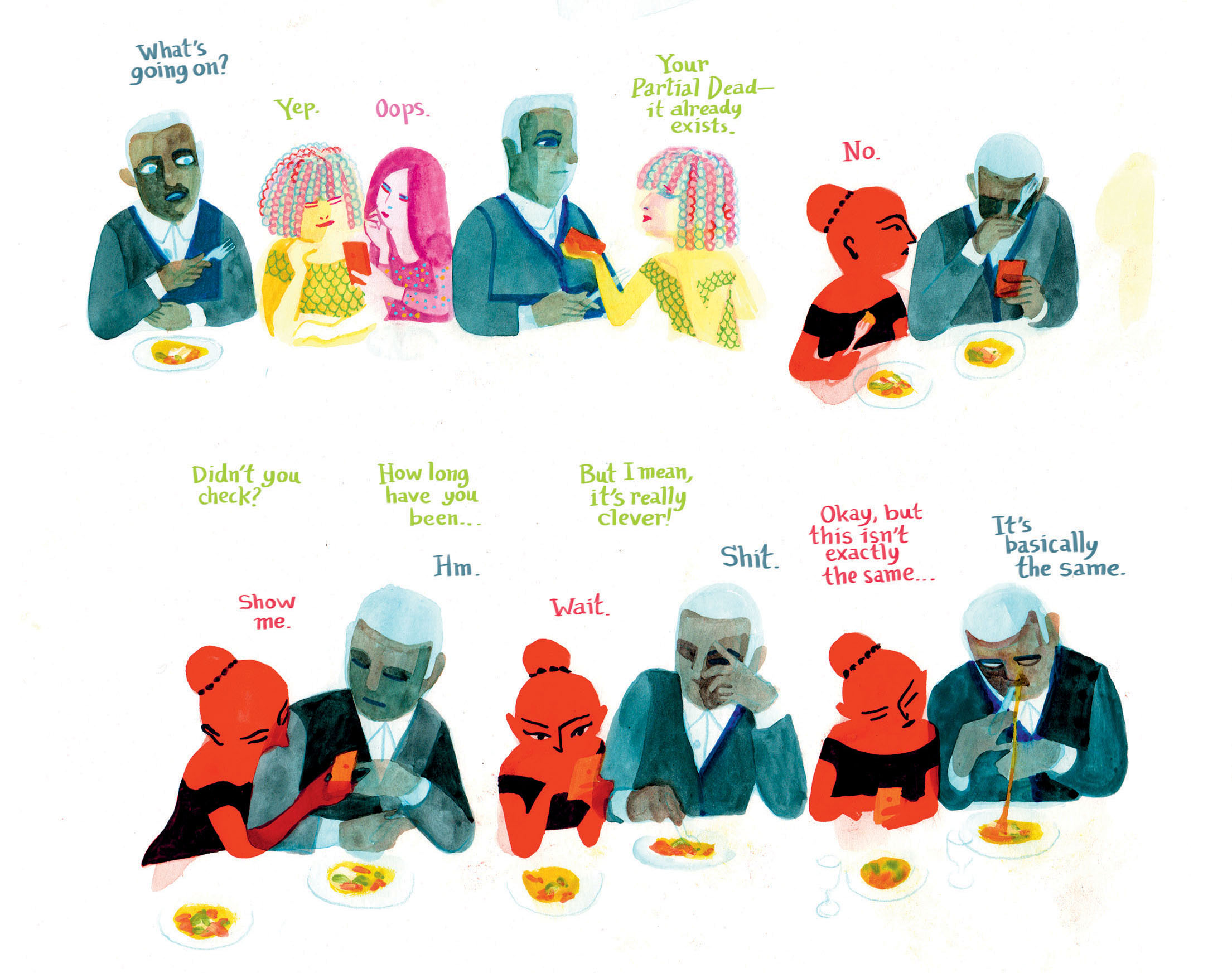

TD: And the other storytelling character is Michael, who is describing his zombie TV show. Which is perfect because it’s a funny, great concept, and somebody says, “Oh, that already exists.”

BE: Michael is the ex-boyfriend of the second protagonist, Victoria. I wanted to do something with her that took some pages, some time. I wanted us to be drawn to her as a main character because of the force of her personality, even though someone else, a dude, is talking all the time. So it takes a while before we see her face. First, we see her from behind, and she has this very distinct hair, these very distinct clothes. And she’s reacting in a spicier way than the other two women sitting at the table.

This was about being confident enough in the character that she will draw us in. Even though she’s just commenting on someone else’s story, she’s making us ignore the guy who’s talking. Even though she has shorter phrases in the beginning, she obviously has way more to say than the guy who’s talking in blocks of texts.

TD: Right, he’s just detailing this loose idea he has, which he has spent a lot of time thinking about, but not trying to nail down.

BE: Yeah. I was nervous specifically about these kinds of scenes when the book came out.

When I wrote them it felt very logical, and I’m getting back to loving these scenes, and forgiving myself for taking the time and the paper necessary for them. Having someone explain a dream in detail over four pages… that’s classically known to be boring.

From “The City of Belgium.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

TD: Right. That’s a tricky thing, putting forward intentionally boring storytelling amid explosions of color and drama.

This is the most fantastic of your realistic books: the things that happen strain credibility a bit with each character. It doesn’t feel like somebody’s typical night out. It’s all very hyper dramatic. The party’s gone on too long.

So you need that early part. Because when I first read The City of Belgium, I worried this part where people are just talking and going nowhere was very long. But you need that to make the rest of the book work. The evening needs to start out a little awkward.

BE: There is a freer kind of reading in this graphic novel stuff. You choose whether to look at the background in detail or not, you make your own way a bit. And you can go fast through things that you can sense are just word spits coming from someone. The medium allows this if used well.

In a movie you would do something with the volume, or with the audio where something gets more backgroundy. Hopefully you naturally find your way like this in a comic.

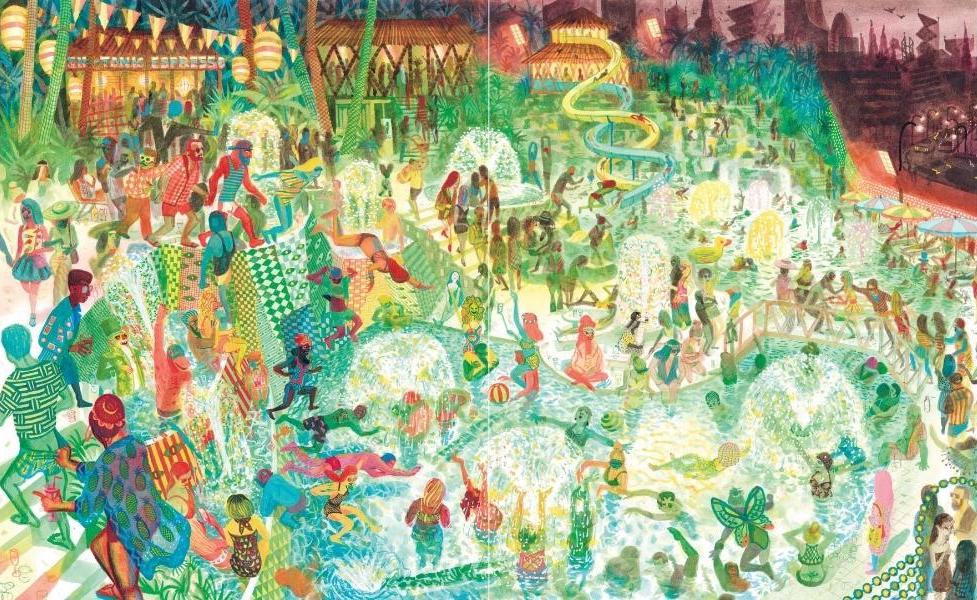

But mostly I wanted these characters to really become alive before they start being chased around the city, and overtaken by the beauty of it. The book is not some kind of farewell to parties, it’s definitely still celebrating the fun of nightlife. I mean, there’s a lot of people obviously having a great time, sometimes including the main characters. But there’s a lot of fun in the background.

From “The City of Belgium.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

TD: Yeah. You just make these big power drawing sequences: a huge spread where you show off your compositional skill. That is something you can do in comics, that you maybe can’t do in other mediums. “Here’s an amazing drawing, take that.”

But you aren’t doing it for the sake of just the drawing; it’s always a narrative element. And like that’s pretty rare. A lot of great cartoonists will strip that out. Not the fun but that explosion, the show-offy-ness so as not to distract from a mood that they want to set. But you’ve found a way to keep that mood while you’re like, “Oh, I’m going to spend a few days doing this homage to this old tapestry. And it will work narratively, AND it’ll be fun.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

From “The City of Belgium.”

BE: I did this 340-page party graphic novel. Before doing any of these big splash spreads, I was still figuring out, what can I eliminate? And how do I accumulate the ideas into one image, instead of spreading them over four spreads?

In the book when we get to emotionally intense moments, the backgrounds often disappear entirely. And we get to focus precisely on movements, on slight changes of position.

The big backgrounds of nightclubs and cityscapes are where the conversation is less important, and it’s more of a vibe. Like in a Scorsese movie, walk into the night club through the little hallways, via the special entrance, and you get shown to your table.

TD: Harvey Keitel’s not moving, and his shoulders aren’t moving he’s just gliding through the club.

BE: Traveling shots you could say, but it’s your eye traveling through it.

_________________________________

The City of Belgium, by Brecht Evens, is available from Drawn & Quarterly.