I have more than 600 postcards from a guy who made them into a literary genre.

If we’re lucky, we can recall that teacher in our lives who helped change the way we saw something about the world by unsettling a previously entrenched perspective on art, politics, or something of the kind. It sometimes happens that this person is also an understated figure, perhaps someone who made a good human interest story in a local paper but otherwise didn’t care about public recognition.

In my own life, that man is David Thompson, an enigmatic former high school teacher who now spends his days in North Carolina doing God knows what. We still email occasionally though I never know what he’s up to. Thompson is a funny, talented poet and photographer, but I mostly know him as the man who transformed the way I thought about how literature can stretch beyond the classroom into the minimal and mundane: the postcard.

Who needs to invest in posters or artwork for the wall when you can cover it with free postcards?

Who needs to invest in posters or artwork for the wall when you can cover it with free postcards?

Thompson was a fan favorite at my high school, a private institution outside of Detroit whose administrators always struck me as comical foils to Thompson’s irreverent Everyman: a lanyard-toting, wise-cracking lover of Elvis and the Beats who would occasionally end classes by putting on an episode of The Simpsons if we’d behaved long enough to listen to a few words on Beowulf or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

I couldn’t articulate why at the time, but these qualities were what made Thompson among the best teachers I’ve ever had. He loved literature but did not need it to be sacred. The classroom was not the only way to receive that education, not even the best necessarily. You might be better served bumping into someone who tells you about a good book on the street (or in a busy hallway).

I don’t know much about his personal life, but I do know that Thompson spent his childhood in the Hudson Valley and Germany, and later spent a significant amount of time in Texas and Detroit. He began sending postcards in batches—ten to forty a day—to an unknown number of people while recovering from a major surgery.

When I started college in 2013, he began mailing me postcards in such great volume that I would be surprised if there was a day without one in my student mailbox. In reality, I’ve managed to hold onto more than 600.

There is a peculiar art to a David Thompson postcard, a formula rarely broken that has delighted me for seven years. On the other side of a compelling image—sometimes a landscape that Thompson himself photographed, a random propaganda poster, a portrait of some cultural figure—is often a quotation from something Thompson is reading at the time. The quote may or may not be the only text he writes.

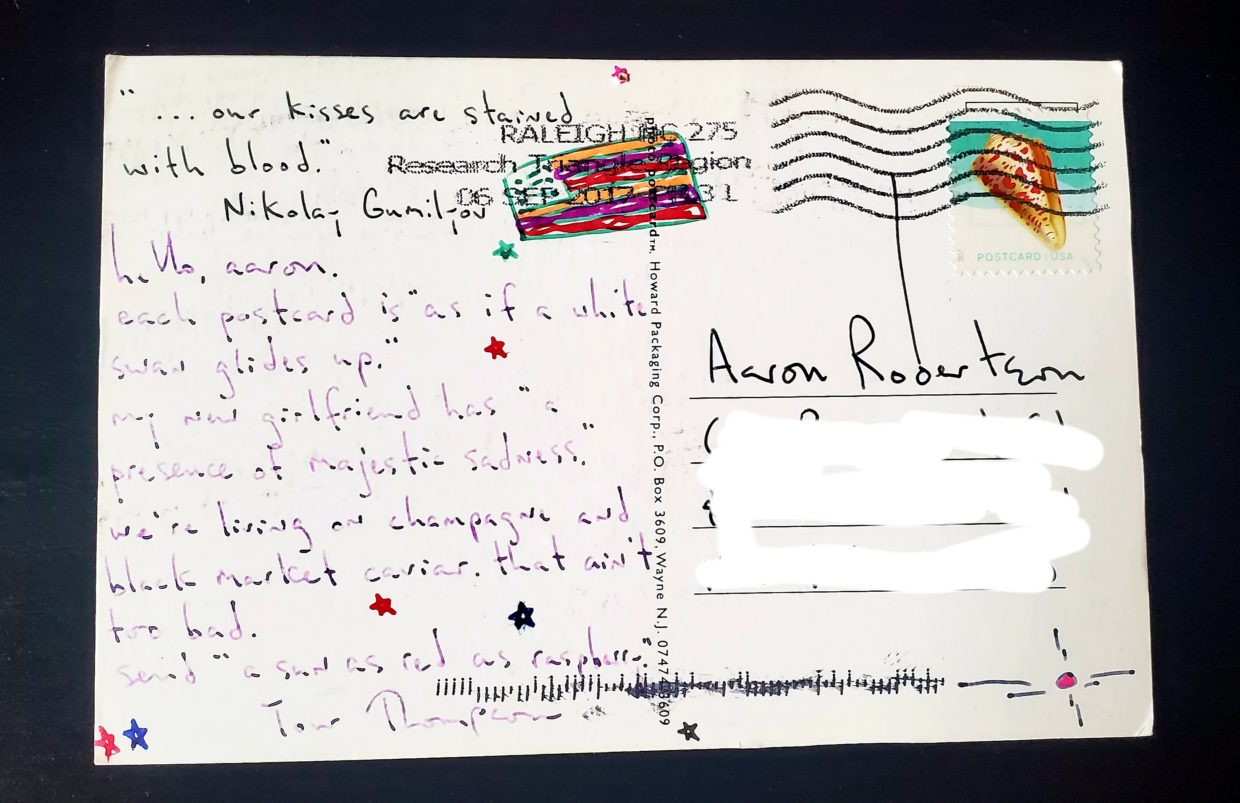

Usually, though, what follows is a poignant reflection on the art of postcard writing and a surreal, humorous yarn about Thompson’s fictional escapades with an imaginary girlfriend. Take this one, which begins with a quotation from Russian poet Nikolay Gumilyov:

hello, aaron. each postcard is “as if a white swan glides up.” my new girlfriend has “a presence of majestic sadness.” we’re living on champagne and black market caviar. that ain’t too bad. send “a sun as red as raspberry.” Your Thompson

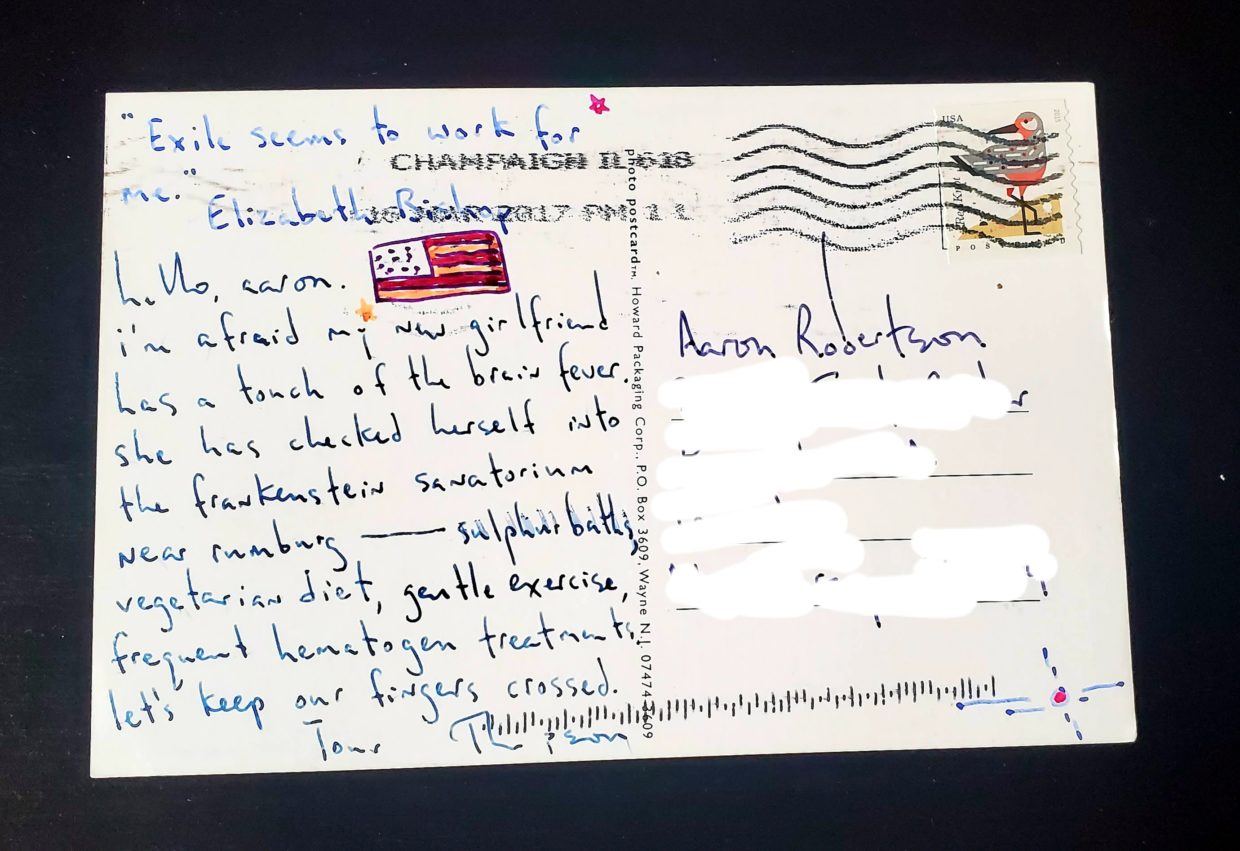

Thompson and his unnamed partner have been through a lot over the years:

hello, aaron. i’m afraid my new girlfriend has a touch of the brain fever. she has checked herself into the frankenstein sanatorium near rumburg—sulphur baths, vegetarian diet, gentle exercise, frequent hematogen treatments. let’s keep our fingers crossed. Your Thompson

Thompson made his own diverse interests an inextricable part of my literary education. The postcards have survived relationships and relocations—they must have followed me to four or five different places—and have taken on the consistency of a morning ritual.

Don’t take my word alone. Poet Kaveh Akbar donated his collection of 1,400 postcards, acquired from Thompson over eight years, to the Newberry Library, an independent research center in Chicago that houses millions of pages of material on everything from the Renaissance to cartographic history and Midwestern writing.

In a 2014 article for The Awl, Akbar said that Thompson had been sending him four or five postcards a week since he’d started college at Purdue. Akbar didn’t know Thompson personally but had admired his work from small-press poetry publishers and magazines like Nerve Cowboy and Barbaric Yawp. “His speakers were down-on-their-luck divorcees,” Akbar wrote of Thompson’s poems, “paunchy factory men at their high school reunions, drunk friends marveling over Mexican death masks.”

Returning to the postcards, Akbar continued: “I have no idea how many other people get cards from him, but it seems to me that those of us in the exclusive club of postcard recipients are privy to one of the most interesting ‘social media’ streams conceivable — a routinely updated feed of visually striking, intellectually compelling, tactile, personalized content.”

With distinctive prose and original photography, a Thompson postcard can feel like an impossibly complete package. In a 2017 interview with Midwestern Gothic, Thompson said he’d been taking pictures since the early 1980s, when he got a hold of a camera during his travels in Asia. His website, Nine Mile Photo, features some of his photography: street art in Detroit, Spain and Prague, a rust-and-ramshackle vision of the American South and Western prairie lands, images from the Great Plains.

Critic John Wood wrote that “Thompson’s America is unrestricted by geography; it is embedded in the midst of all those other Americas. It is the America of losers … Tragedy, irony, humor, and general oddness all blend into a single vision.”

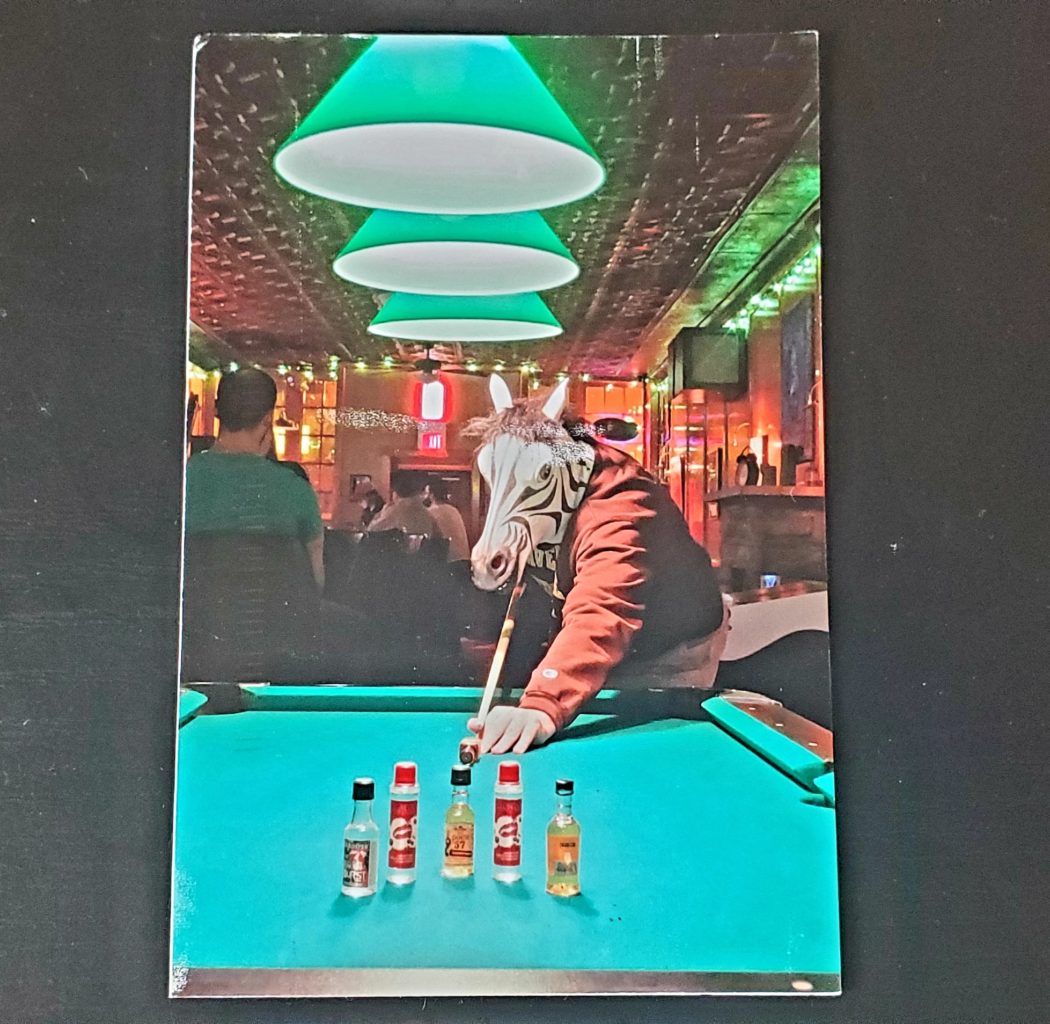

I hope Thompson uses this as the author photo for his next chapbook. That is, in fact, him under the mask. I’m personally partial to his horse and dog masks.

I hope Thompson uses this as the author photo for his next chapbook. That is, in fact, him under the mask. I’m personally partial to his horse and dog masks.

Because I’ve known Thompson for a while—at least, in the way you know the location of your favorite corner store or bodega without knowing what the cashier’s deal is—I’m still a bit surprised more people haven’t recognized just what a treasure his work is. Then again, the kind of acclaim I’m thinking of is exactly what he is writing and photographing against. To paraphrase something he said, the point is to get off the interstate and take a country road.

Thompson’s short poetry/photography collection It’s Like Losing (2017) is worth a read if I’ve sold you on his work. I’ll leave you with one of my favorite poems from him, “Circus Train”:

They weren’t funny anymore,

the three clowns I found lying dead

in my front yard this morning

when I walked out to get my newspaper.

Their bodies were clawed and half-eaten;

garish, bloody clothes, oversized shoes,

and fake red noses strewn across my lawn.

I bent down to pick up my copy

of the local rag off my driveway,

glanced at the big headline that read

CIRCUS TRAIN CRASHES:

LIONS STILL ON THE LOOSE.

I immediately jumped on one

of the elephants standing next

to my mailbox, rode it back

to the house as fast as I could.

Once inside I locked the door

behind me, walked to the kitchen

for a fresh cup of coffee. I glanced

at the sports page, grabbed a pencil,

then sat down like I do every day

to work the crossword puzzle.

Aaron Robertson

Aaron Robertson has written for The New York Times, The Nation, Foreign Policy, and elsewhere. His translation of Igiaba Scego's novel Beyond Babylon (Two Lines Press, 2019) was shortlisted for the PEN Translation Prize and Best Translated Book Award.