“I Feel Like a Feather Floating in the Atmosphere.” How Thoreau Reckoned with the Loss of His Brother

Robert D. Richardson on the Writers’ Grief-Stricken Observations

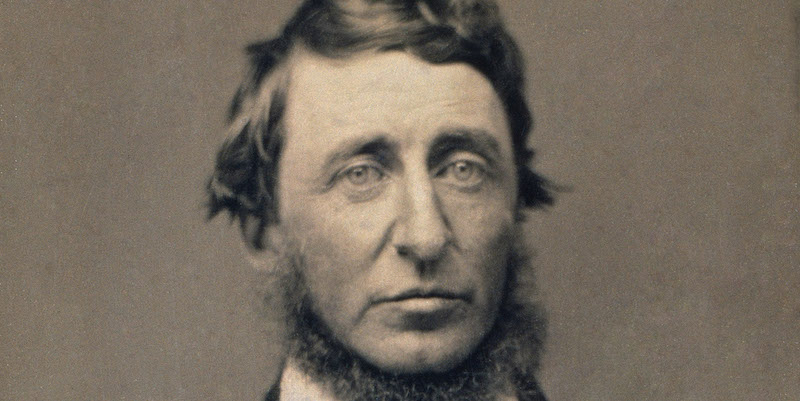

On the last day of December 1841, Henry Thoreau, then twenty-four years old, wrote a 450-word entry in his journal, starting with the observation that “Books of natural history make the most cheerful winter reading.” He mentions Audubon, the Florida Keys, Labrador, and “the snow on the forks of the Missouri.” For three paragraphs he insists on the “singular health” he finds in such reading. “In society you will not find health, but in nature,” he writes. “I should like to keep some kind of natural history always by me as a sort of elixir, the reading of which would restore the tone of my system and secure me true and cheerful views of life.”

The next day, a Saturday, New Year’s Day, 1842, dawned in Concord with clear skies, but turned cloudy and squally. It was a day like any other, except that Henry’s brother John, three years older than Henry, cut himself on the ring finger of his left hand while shaving. He thought nothing of it, wrapped a bandage around the cut, and went on with life as usual.

Henry was working at his journal, as he usually did for a part of each day. He was reading Chaucer and liking it. A couple of days later, on Monday, January 3, he made popcorn, which he playfully called “cerealious blossoms” because they were “only a more rapid blossoming of the seed under a greater than July heat.” On Wednesday, January 5, as early clouds gave way to midday sun, he praised manual labor as “the best method to remove palaver from one’s style.” Maybe he took his own advice about palaver. We hear no more from him about cerealious blossoms.

On Saturday, January 8, eight days after he’d cut himself, John found his cut “mortified,” that is, gangrenous. He walked to the town doctor, Josiah Bartlett, who dressed the wound and sent him home. Leaving the doctor’s house, John felt weak and barely made it home. The next morning, he felt his jaw muscles stiffening. By evening, lockjaw (tetanus) had set in. Henry became John’s nurse, but John’s condition deteriorated fast. The next day, Monday, January 10, a Boston doctor was sent for, came out to Concord, and pronounced the case hopeless. Hearing this, John is reported to have said, “The cup that my father gives me; shall I not drink it?”

Henry was unable to get out of bed for four long weeks, and while he did return to his journal on February 19, it was a week more before he could write any letters.John died the next day, Tuesday, January 11, in Henry’s arms. He was twenty-seven. We have few details about his passing, but it was probably not peaceful. In many tetanus cases the rigidity spreads, often affecting the neck, then bends a person over backward, as depicted in a terrifying painting by Dr. Charles Bell, Tetanus Following Gunshot Wounds (1809). Henry is reported to have told a friend that John “was perfectly calm, even pleasant while reason lasted, and gleams of the same serenity and playfulness shone through his delirium to the last.” The references to “while reason lasted” and “delirium” suggest that Henry was putting a good face on a scene that was not all calm and serene.

John had never been in good health. Three years older than Henry, John was of short stature, frail and thin, weighing just 117 pounds. In marked contrast with his brother Henry, John was quiet, genial, and neat. He had frequent nosebleeds, some of which, occurring when he was eighteen or so, were so violent they made him faint. He was often sick, calling his condition “colic,” but the underlying problem was tuberculosis. He found teaching a strain, and he and Henry had to close their little Concord school in 1841 because of John’s poor health.

After John died, Henry walked to his friend Emerson’s house, where he had stayed occasionally before John became ill. It was snowing; the thermometer registered 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Henry went to talk with Emerson and would talk to no one else. Next morning he came back, collected some clothes he had left at the house, told Lidian he didn’t know when he’d be back, and left for the Thoreau family home. With John’s death, Henry’s journal stopped abruptly.

*

Thoreau made no journal entries for the next five weeks, though the wide world rolled on. On January 11, the same day John died, William James was born in New York City, and would soon receive a visit from Emerson, a friend of William’s father. On January 13, Dr. William Bryden, the sole survivor of a British Indian army of 4,500 men, staggered into Jalalabad in India following the catastrophic “retreat” from Kabul, during which the entire invading army had been wiped out in the mountain passes of Afghanistan. On January 22, Charles Dickens and his wife arrived in Boston by ship from Liverpool and were met by a dozen newspaper editors who swarmed aboard for interviews. On the same day, the Thoreau family in Concord was shocked and horrified as John’s younger brother Henry suddenly developed symptoms of lockjaw himself.

Henry had not cut himself, his skin was not broken, and tetanus is not contagious. Henry’s illness was a two-day sympathetic reaction, an emotional response not unheard of even then. Emerson reported to his brother William on January 24 that Henry was better. But the terrible January was not over.

That same evening, Emerson’s five-year-old son Waldo contracted scarlet fever, a disease for which, like tetanus, no vaccination or treatment existed at the time. By January 27, the child was delirious. When his mother, Lidian, asked Concord’s Dr. Bartlett, who had made a house call, if Waldo would soon be better, he responded, “I had hoped to be spared this.” A few hours later, at 8:15 in the evening, the little boy died.

The grief in the Emerson house was all-consuming. When nine-year-old Louisa May Alcott came to the door to inquire after Waldo, she was met by his thirty-eight-year-old father. Emerson was so stricken he could not bring himself to speak the name either of his boy or the girl at the door. “Child, he is dead,” was all he could manage. Alcott later said this was her first experience of a great grief.

Usually so perfectly attuned to sounds, especially natural or musical, Thoreau now feels untuned, even lost: “I never saw to the end nor heard to the end but the best part was unseen—and unheard.”But Emerson wrote at least ten letters immediately—four that same night—pulling himself together by forcing himself to turn outward toward others. “I comprehend nothing of the fact [of Waldo’s death] but its bitterness. Explanation I have none. Consolation, none that arises out of the fact itself: only diversion: only oblivion of this, and pursuit of new objects.” In the Thoreau household, there was silence and a terrible inactivity. Henry was unable to get out of bed for four long weeks, and while he did return to his journal on February 19, it was a week more before he could write any letters. When he finally resumed correspondence, the letters had a preternatural calm. And the journal entries that preceded them carried a forced quality.

*

Thoreau’s first journal entry after John’s death, made on Saturday, February 19 (and it really does seem to be the first, not just the first that has survived), is a mistrustful, rather grim set of observations on a recent visit, almost certainly by Emerson. “I never yet saw two men sufficiently great to meet as two,” Thoreau writes, focusing on his relationship to Emerson and bypassing the expected conventional expression of regret or sadness for each other’s recent losses. “When two approach to meet they incur no petty dangers, but they run terrible risks.

Between the sincere there will be no civilities,” Thoreau goes on. He means there must be honesty and sincerity. Maybe civilities were extraneous for Thoreau at this low moment. Sincerity was its own reward, but it had other benefits, too. It seems highly likely that on this first trip on February 19 to see the stricken Henry, Emerson brought him a book just published by Elizabeth Peabody, Guillaume Oegger’s The True Messiah, for this is what Thoreau was reading and taking notes on the next day, Sunday, February 20.

Oegger was a Swedenborgian who believed that because everything in nature stands for something in mind, the entire physical world then functions as a visible language, a collection of emblems we can decipher. (Swedenborg would be a huge influence on Henry James Sr., the father of William and Henry.) That Thoreau was now reading Oegger is a small signal that he was starting to get back on track. Emerson probably intended—or at least hoped—as much. And indeed, the idea that nature is a language we can learn to read would stay with Thoreau right up to the last entry he ever made in his journal about how we can see, in the gravel of the railroad beds after a storm or a rain, how each rain and wind is self-registering.

The brief bit from Oegger that Thoreau entered in his journal for February 20, 1842, is positive in its understanding of a connection between nature and mind, but the entry (clearly inspired by Emerson’s visit and his gift of the Oegger volume) is not typical of Thoreau’s state of mind in that February week. Far from positive, Thoreau’s mood was querulous, grouchy, self-critical. “It is vain to talk,” he grumbles in his journal. “What do you want? To bandy words—or deliver some grains of truth which stir within you? Will you make a pleasant rumbling sound after feasting for digestion’s sake? Or such music as the birds in springtime.”

Thoreau feels displaced just now, and unsure even of his unsureness. The next day, February 21, he writes in his journal, “I must confess there is nothing so strange to me as my own body. I love any other piece of nature, almost, better.” It’s that “almost” that signals trouble. And there is more trouble in his preternatural sensitivity to sound: “I was always conscious of sounds in nature which my ear could never hear… she always retreats as I advance.”

Usually so perfectly attuned to sounds, especially natural or musical, Thoreau now feels untuned, even lost: “I never saw to the end nor heard to the end but the best part was unseen—and unheard.” This is not the usual “heard melodies are sweet but those unheard are sweeter,” not a recurring Platonism, but, as befits someone who loved real, actual sounds, a feeling of being lost, unable to hear something all the way to the end. And not only lost, but weightless: “I feel like a feather floating in the atmosphere, on every side is depth unfathomable.”

___________________________________

Excerpted from Three Roads Back: How Emerson, Thoreau, and William James Responded to the Greatest Losses of Their Lives by Robert D. Richardson. Copyright © 2023. Published by Princeton University Press and reprinted here by permission.