The mirror in the plane bathroom had fingerprints all over it and fog-thick grease where the soap had back-splashed. One hour into the flight, plenty of hands had been busy here. I scooted in and pushed at the latch with a knuckle. The light flickered and brightened but the bolt stuck midway. I swallowed hard and drew a paper towel to wipe the glass. The grease was still there, I’d just spread it around. I pushed down the faucet and destroyed the soft-bodied soap-thing, then ran my finger under the drip and tried the stain again, not its reflection on my skin. And the mirror cleared, to show flesh and marks of teeth.

I looked away and pulled two more towels from the dispenser and put them down on the toilet seat. The sheet on the left sucked itself to the plastic ring, catching urine, shrinking. The broken light flashed like a strobe. Bright, then half-dark. I pulled down my jeans and lowered myself slowly, trying not to touch anything. There was a sudden burst of turbulence and I dropped onto the seat, turning my head to see my face.

I saw the indentation below my bottom lip where I had been biting down. Lit by the blue pallor of the light above, the red streak appeared half-black, like in an old movie or cartoon, or an X-ray machine, like the skeleton of electrocution through a shocked body. Another brand in black and blue. This had happened before, broken skin begetting scars. Like when I gnawed my thumbnail and made the quick bleed. I would taste it, touch my face. My eyelids drooped and I sat there, head in hands.

Five times people tried to enter and five times I ignored them. Fist rapping, dramatic sigh, exasperated breaths coming closer as the person eyeballs the “CANT” on the lock.

“Someone’s been in there a really long time,” my latest persecutor said loudly. Turbulence hit again and I bit on that poor piece of face again as my head jerked down, brushing against the hinge in the door. The light flickered and I looked up. The gold of my choker lit a spark in the mirror. My left hand still held my chin. My right flew to my forehead covering my eyes. My ass—still dry on the right-hand side, at least—clenched spasmodically. I stayed that way until a sixth person banged on the door. It could have been hours, but the flight only lasted two and I’d watched half an action film already. A silent action film. I refused the headphones.

“One minute.”

I stood up and buttoned my jeans, turned around and angled my foot to press down the lever. There was the blue light-up dot high on the facing grey wall. Then, the overhead light again, illuminating a dust cloud in the stale air.

I kicked backward into where the door flexed. It gave, and I slid out, barely enough space to get past the waiting man. I had to stop myself from kneeing him reflexively. My body felt tangled, stoppered-up, violent.

How much longer until we landed in Bozeman? Would I be allowed to wander up and down the aisles until then? Make a scene. “Her face was bleeding, and she wouldn’t sit back down.” Only white beyond the porthole windows. I decided to regain my seat and study the foldout cartoons on how to escape in an emergency.

In the air somewhere above Montana, because of the Director’s betrayal. And the comfort of him not knowing where in the world I’d landed, of him not seeing me again until there I was, writ large on some poster or movie screen. The hum of thinking this numbed the reality. It was how my mother still had to face my father after she’d left. Not across the table, but in the Paris metro. His face magnified on a poster on a platform wall. Look at my face. Does this make you remember me? A blank of the reality.

I knew the Director had the strange ability to put blinders inside his head cavity. Like a baby when his mother ducks behind the couch for the plastic ball. He’s all alone. She has gone from his world! The Director communicated with you in the early stages of a play like you weren’t there to begin with. Every message to the future read as blank. You can answer if you want, no obligation. Some cut and paste. A conversation with himself; any response would be beside the point. He didn’t evolve, you adapted. He never checked his phone when he wanted it that way. When he wanted to be elsewhere, a call soon came.

A run-in is always a possibility when work is a common project. And this would run in and out, off and on. My work meant showing up in a local theater or playhouse or on smaller screens. I could try to be in his hands again, making choices, gaming auditions and agents, climbing and webbing. Running around pretending, mastering my thoughts and body. My parents had tried to escape each other at “work,” except they were forever united by it. Professionalism leaks out all around. “All Around” was the name of one of my mother’s near-hits.

Lucy was right. She said to beware of casting myself as a victim. I may have wanted something else, but I stayed for what wasn’t offered. It wasn’t abuse. Not this time, anyway. I waited in the aisle by my row for a few seconds until the woman with the purple-rim plastic visor looked up through her pane of cheap iridescence. She turned back to the tiny screen of the facing seat, pulling her knees up over her belly. I let my back obstruct her view of the movie for an extra spiteful second. She inhaled, annoyed. I bit my lip harder as I closed my eyes and sat down. Turning my face away from her, I pressed into the oval porthole. I used to do this as a child on the train. Close your eyes, push your head into a corner. The colors will come. I pulled down the plastic blind and tried to wedge my head into the shallow corner.

A memory of being in a train car. I touched my chin and it was wet. The back of my hand swiped it clean. A grid of coordinates from the stain in the bathroom mirror registering my body’s orientation. Dried red on my sleeve from an earlier swipe. How much longer? The intercom answered. The local temperature at Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport. Seatbelt. I kicked my backpack farther under the seat in front. The woman next to me had shifted from annoyance to disgust. She stared at my chin through her face shield. I looked away and closed my eyes again so I wouldn’t have to meet hers. She started tapping my clean hand on the armrest between us. I breathed in hard, trying to calm myself. Look at her. That unnecessary face shield, an artifact from a recent past that already felt an age ago. The early style, before they grew more ergonomic, thinner. “Lady, your chin,” she said. “Or maybe your nose is bleeding?”

I found a clean bit of sleeve on my forearm and held it up against my face, as bandage and wall. She looked away, edged closer to the aisle. Now I tried to meet her eyes. She was afraid of me. And we both had to stay there until landing.

Last time I’d flown it had been the opposite, I was an attraction for my seatmate. He had identified me by the mark at my hairline. “Hi, I’m Jay. I’m a fan of your mother’s.” Her kind of acolytes were like this, devoted. They knew about all the little things. Like my birthmark. Every one of them had a memory of a gig or a song. They always had something they wanted to tell me.

The worst ones wanted to talk about the couple, Rose Reeder and Steve Highsmith. About how she was from a music family and he was from . . . outside Detroit. About how they had The House, and all these sincere ideals and dread of selling out. About collectives and self-parody. About dropping in and dropping out. About Rose leaving

Steve to go off with the other guy in an attempt to disappear. Did they not get that these were my parents; that I was the only person alive to have already, and exhaustively, thought through all these things? Like my father’s face looming in the metro, these strangers’ secondhand hot takes changed people into outsize reproductions.

Unlike Jay, the lady with the face shield cared only to prevent me bleeding or sneezing anywhere near her. Near her in the sky. Like at the end of a relationship, sensing that someone itches to get away but feels they have to stay a little longer. She kept her body jammed to the aisle side. I kept my head pressed to the wall. Up close, I could see the surface was printed with faint violet spirals. The wheels dropped and the plane landed. I straightened up, the woman flipped her hair and said, “Lady, you should deal with that.” I pulled the collar of my t-shirt over my nose like a mask. She seemed satisfied by this gesture and stood up, turning to the overhead compartment. The color of the arms of her shield matched that of her rolling luggage. I waited until everyone left, stood up, and put my backpack on.

I walked out of the plane, round the accordion bend of the bridge, like the top part of the plastic straws I remember from the coffee shop as a child. Lucy had told me the airport was small, but it was smaller and warmer than I expected. There were yellow wooden beams and bronze effigies of wildlife. The carpet was a crosshatch of eggplant and green. The one souvenir shop sold stuffed moose and bears, M&Ms, and tabloids with neon headlines:

“Rachel’s Turning 15! I Don’t Want to be Famous Like My Mom.”

“Jennifer & Will Burying the Hatchet after 20 Years!”

“Reboots and Revivals Coming Soon!”

A few paces and I was past check-in on the way out. There were women and men in purple navy polyester vests. The plaster walls were camouflaged in gray-beige marbling. After two vitrines of dinosaur remains, I exited onto the Montana street.

I realized I hadn’t brought a coat or anything warm enough, really. The autopilot rush of getting here from New York had been the most I could handle. I touched my neck, flicked the gold trim of the choker, then felt for the plastic clips on the base sides of my backpack; buckles where you could tighten the straps. I grasped one in each hand and steered myself forward.

There was an older woman waiting on the sidewalk, making expectant eye contact, holding a heart-shaped mylar balloon. It had been a long time since I’d been somewhere that smelled like this. Whiffs of pine and weed and gasoline. I noticed the woman with the visor standing at the curb, signaling to a black sedan. She looked back at me and then away, as if she didn’t want me to know I still figured in her cares. She crossed the street towards the breezeway.

I wanted to call a cab, but I had forgotten Lucy’s address. It was way back deep in our text messages, messages in which we’d gone over and over what had happened with the Director until none of it made any sense, where she said what needed to be said again and again. That he was an asshole. That I was not a victim. And this line from Chantal Akerman she often quoted: “Souvent je ressasse et je travaille autour du manque, du rien, comme dit encore ma mère.”

All her references came from her father, the late critic Christopher James. He was born in Oregon but ended up in Paris in the late ’60s. When Lucy was born, he was fifty-seven and had just wrapped his one and only movie, bankrolled by Godard. He then retired to the small town outside of Livingston, Montana where right now I was planning to stay indefinitely. He and Lucy’s mom, Patricia, had a place with a studio out back where he would write and watch movies. I scrolled to the photo Lucy had sent me of the house with the address: 57 Plinth Road. Copy and paste. In three minutes, a minivan was on the way to pick me up.

I refreshed my email and saw that my father had sent the contact details of ten music friends. There was a band called Silkworm who came from nearby, and the widow of the drummer lived close to Bozeman. His list contained people who were “decent, Margot.” Always repeating my name. “They will help you hide away, because they are always trying to hide themselves.” My father added that I should consider taking this time to pause the acting, to write my own stuff, to look for local theater productions, something more real. Arriving in Montana would not be unlike arriving on set. New location, unfamiliar crew. Here we go, the same story heard over and over again, but in reverse. A Hollywood-type thing: girl leaves small town for the big city. Shared stories and lyrics. From one bad relationship to the next. Fled to the Pacific Northwest. I thought I could get away from songwriters and filmmakers and the people who do their go-between business.

The purple shield woman was still trying to fit her luggage in the backseat of the sedan. She got in, bending over, her ass held in hot pink bike shorts. The door slammed as she sat straight, peering out, clocking me. She’d taken off her visor to press her face into the window like a child watching a jail transport bus roll by. Me, the prisoner in the open air. Her, safe in the back there.

Everyone who looked at me—even the Director—came loaded with ideas about me. Fascinated by all the family signifiers, he never noticed the reality. Behind the scenes, fucking what didn’t exist. Actress whisperer. Seducing secondhand access. Daughter-of is never lateral. It expands in all directions. Maddening for me that the public version of my parents was made out of not caring. Trying to turn away from optics and hierarchies. The cheap refrain from “All Around”:

“Power destroys the individual. Collective sigh.”

The van pulled up next to me. On the window, “fuck you” written with a finger in pollen dust. I could see the reflection of a ring stain below the neck of my shirt. Blood and spit in a faded soft puddle. This new double moved aside on the sliding door and I climbed in.

“Margot Highsmith?”

__________________________________

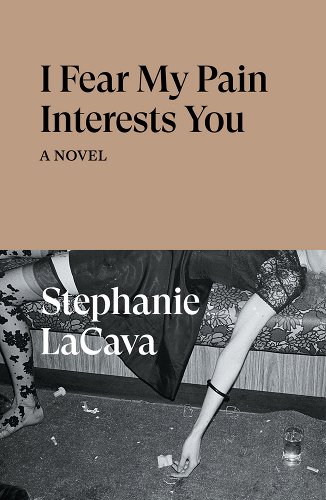

From I Fear My Pain Interests You by Stephanie Lacava. Used with permission of the publisher Verso. Copyright 2022 by Stephanie Lacava.