I Am Spasticus! On Discovering You Have Cerebral Palsy

Greg Marshall Considers a Long-Held Medical and Family Secret

Philip Roth once wrote that there aren’t many words less abstruse than “leg,” but it’s taken me a lifetime to understand mine. I wish I could say my leg fought in a war, or had a drug problem, or escaped a polygamist cult, or smoked cigarettes with Gertrude Stein in Paris in the twenties, perhaps while wearing a beret and writing poetry. That leg would be worthy of a memoir!

“You can’t call your book Leg,” my mom told me when I brought up the idea. We were walking under the stars in Costa Rica, on the same beach where my big sister, Tiffany, would be married the next afternoon. The sand under my feet felt therapeutic in a vaguely menacing way, like walking on ball bearings and lug nuts. I have very sensitive feet.

“Who would want to read a book called Leg?” Mom asked.

“I would,” said my mom’s partner, Alice. “I think it sounds intriguing.” She was drawing what looked like vaginas in the surf with her big toe, calmly avoiding scuttling crabs that left my little sister Mona and me squealing. Alice made jazz hands at the crabs. “Leg!”

“The thing is, I didn’t ask about my leg because I thought I already knew everything there was to know about it.

“Don’t agree with him, Alice. That’s not your job.”

Keeping Mom alive, that was Alice’s job. Getting Mom, a sixty-year-old cancer patient, to this exclusive peninsular hideaway, that was Alice’s job.

The journey from Utah had required, among other things, flying over a Neverland of sparkling ocean in a tiny propeller plane and then cramming into an off-roading Jeep. We all knew that Alice, my mom’s doctor-turned-lover-turned-perpetual-fiancée, was the only person on the planet with the skill and will to do it, the only person who could Weekend at Bernie’s Mom down the aisle on Tiff ’s big day, if it came to that. Plus, Alice would know what to do with my mom’s body if she died in Central America. If it were up to us, we would just take her out in a snorkeling boat and roll her into the ocean. We might even do that before she died.

Having a mom who’s been battling cancer since I was in the second grade has turned me into a morbid bastard, and my four siblings are no better. When your mom is always dying, you think she never will.

“I could call it The Kid with the Limp,” I said.

“Jesus!” Mom said. “That’s even worse.”

We walked for a while in silence, listening to waves crash against the shore while taking in the distant flicker of tiki torches at Tiffany’s rehearsal dinner farther up the beach.

Alice was squinting up at the sky through her nerdy rectangular glasses, trying to point out some constellations, when my mom interrupted her. “You know what’s a great story? It’s a Wonderful Life.” I was almost positive my mom had never sat through It’s a Wonderful Life—she hates black-and-white movies—but I let her continue for argument’s sake. “Why don’t people tell stories like that anymore? It’s a Wonderful Leg. That’s what you should call your book. It’s a Wonderful Leg and There’s Absolutely Nothing Wrong with It and My Mother Did the Best She Could in Spite of Having Cancer and Five Kids and a Husband Who Died of Fucking ALS.”

Well, there you have it.

I was almost thirty when I discovered, quite by accident, that I have cerebral palsy. No one had ever told me about my diagnosis, not my physical therapists or my orthopedic surgeon, and certainly not my parents.

I’ve always walked with a limp and I spent a good portion of my childhood in casts, leg braces, and physical therapy, learning how to hop on one foot, skip, and touch my shins (my toes being forever out of reach). But as the middle child of five kids in a rowdy family where someone was always almost dying or OD-ing, I didn’t ask too many questions, or, rather, the questions I did ask had nothing to do with my leg and were mostly muttered to myself: Was it possible to get an STD from a Brookstone back massager? Did my voice sound too nasally? How much would ass and calf implants run me, ballpark?

The thing is, I didn’t ask about my leg because I thought I already knew everything there was to know about it. It was just a leg.

Imagine that.

*

I was born among the Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis of East Peoria, Illinois, in a red-turreted hospital off Interstate 74. Scheduled to pop out vaginally the week after Thanksgiving, I was instead evicted by Cesarean in the predawn of an October morning in 1984, not more than eight hours after Mom started leaking amniotic fluid mid-frame at her monthly Entre Nous bowling tournament.

On my birthday, she liked to retell the tale of my traumatic birth. It involved her doing a headstand in her hospital bed to get me off the umbilical cord and concluded with me spending sixteen days in infant intensive care. At nine months, when I tried to pull myself up to the coffee table or couch, I sprang to the ball of my right foot, my tippy toes, and limped so badly I wore out the tops of shoes rather than the bottoms.

The brusque orthopedic specialist who diagnosed me with cerebral palsy at eighteen months didn’t appreciate the fact that I peed on the floor of the exam room. “He’s incontinent, too?” he allegedly said. Trying to lighten the mood, Mom noted my stifled, shuffling trot by quipping, “My son walks like Herman Munster.”

My leg was what brought us to Salt Lake City. Before my fourth birthday, we moved from our small town in Illinois for my first surgery: an Achilles tendon release on my right side. It would be the first of a handful of operations over the course of my childhood to relieve contractures in my heel and hamstrings, bringing me off my toes and freeing my gait.

As I got older, my parents simply told me I had “tight tendons” and left it at that, making it sound like I suffered from a vaguely Homeric physical ailment rather than a neurological one. My leg was nothing serious. Those pesky tight tendons, they just needed a little loosening up!

I can understand their flawed logic: My folks didn’t want me to feel crappy about myself, didn’t want me to stare down a lifetime of diminished expectations. They made the inherently ableist and probably correct-given-the-time-and-place calculation that it was safer for me to try to pass as an everyday, Wizard of Oz–loving, acne-riddled, thinks-he-can-actually-speak-French dork with a trophy case in his room full of collectible Barbies rather than as a kid living with a disability.

Every day growing up was like an ABC Afterschool Special in which no lessons were learned, no wisdom gleaned.

And so, my childhood continued apace, filled with Nerf wars, school musicals, tennis lessons, pretend news broadcasts from the living room, and my mom’s never-ending battle with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. You know, typical kid shit.

Mom and Dad were both born and bred in southern Idaho, so moving back to the Mountain West was a sort of homecoming. We have Mormon relatives on my dad’s side but because of my mom’s Basque upbringing—the result of adoption, not genetics—we were raised Catholic. I suppose being outcasts on religious grounds in a predominantly Mormon neighborhood provided a kind of pre-education for being gay and disabled.

Our training in the ways of the Beehive State was what you’d call practical rather than theological and it would continue, in one way or another, for my entire childhood. Whether you want it or not, when you live in Utah you get the dirt on polygamy and missionaries and baptism for the dead, black magic, and golden tablets. As a general rule, Mormons can’t stop talking about being related to Brigham Young and non-Mormons can’t stop bitching about the state’s restrictive liquor laws.

Our suburb, Holladay, didn’t have a seedy underbelly. It had an undergarment. If you didn’t know what to look for, you would think Holladay was like anywhere else, the ghostly outline of its strangeness just visible under the most ordinary clothes.

Like many other houses in Holladay, our big redbrick 1980s family home had been built with a plethora of walk-in pantries to stockpile nonperishables for the End Times. Picture a place where salvation is served like a warm plate of cookies left on a doorstep. A seminary building or ward—with its needlepoint steeple and satellite dish tuned to the signal coming from Temple Square—was conveniently within walking distance of every public junior high and high school so kids could receive religious instruction as part of their school day. The Church owned, and still owns, the local NBC affiliate. When I was a teenager, they didn’t air Conan until past midnight and they didn’t air Saturday Night Live at all. These were grave affronts. Who wants to sit through reruns of Suddenly Susan and Mad About You when you’re in the mood for Camel Toe Annie and the Masturbating Bear?

In this von Trapp world, the Marshalls stuck out.

I’d like to think I’m not the sort of aging gay man who plops down at lunch and comes at you with a hundred crazy stories, but of course I am. I have one of those families. I once overheard someone at a party describe us as a bunch of unlikable assholes who happened to have a great dad—and that was coming from a friend. We’ve been through a lot and none of it seems to have made us better people. It’s just made us more us. Every day growing up was like an ABC Afterschool Special in which no lessons were learned, no wisdom gleaned, and I think at some point it started to annoy people, or just exhaust them.

It wasn’t until I left Utah for college in Chicago that my secret case of cerebral palsy started catching up with me, a stalker lurking in the shadows of my every thumping step or spastic gesture. In that era of great reinvention, I was paralyzed—sometimes literally—at the prospect of having to make so many first impressions. A lot of the time when I tried to talk to someone my leg muscles would tighten up, my toes writhing in my shoe.

People would ask me why I was wincing and I wouldn’t be able to explain, not really. Nor would I be able to get away. I spent every bit of my social energy making sure no one saw me walk or move awkwardly. It was futile. “Do you have cerebral palsy?” an acquaintance asked when he saw me try to put on my coat. “What? No? My jacket’s just a little small.”

Even now, I’m not sure if he was being intuitive or bitchy. The guy had two thumbs on one hand and a crush on me, so I’ll go with the former. Just recently, it got back to me that the first dude I hooked up with at Northwestern called me Peg Leg Greg to his roommates. Now that I’m on more than a nodding acquaintance with my weakest appendage—my dear leg turning, over the years, from stalker to fellow traveler—I find it sort of funny that my first name should rhyme with the biggest mystery of my life, but had I known of this nickname at the time I would have been devastated. I remember asking my mom if it would be easier if I did just have a fake leg, something I could explain with knock-on-wood swagger.

If anyone asked if I was limping, I’d tell them it was just the old tight tendons, attempting to field queries in an unconcerned midwestern fashion that was the opposite of how I felt.

I uncovered my secret case of CP in 2014 while applying for health insurance. For weeks afterward, as I turned thirty, I found myself alternating between a teenage state of woundedness and acceptance as I jerked myself around town by my hair, pointing out the world’s unfairness: cracked sidewalks, uneven stairs. Google taught me addictive new catchphrases like “spastic” and “ableism.”

It’s a wonderful leg and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it and my mother did the best she could.

“That’s ableism!” I told my boyfriend Lucas. (I’d later convert him to Husband, top him for the first time after a Renaissance fest, and write about it for the internet—you really should buy my book.) I made Lucas film me walking in our parking lot, seeing how I moved from the outside for the first time. I cringed the way you do when listening to a recording of your voice, not because it’s so awful but because it’s yours: the scraping toe, the bent knees, the hitch in my step that suggested the way people hoof it in old films, smiling self-consciously.

I rewatched the episode of Breaking Bad where Walter teaches Walt Jr. to drive, this time teary-eyed. I looked up Geri Jewell, the first actor with CP to have a recurring role on TV, and fantasized about showing up to the Planet Fitness where I pounded away on the treadmill in one of her famous pink T-shirts, the kind she’d worn on The Facts of Life: I DON’T HAVE CEREBRAL PALSY I’M DRUNK.

“Think about it, Lucas,” I’d say. “Some hot, normal person walks into the gym wearing that shirt? Everyone’s mind would be blown!”

“Or maybe they’ll finally get why you almost die every time you run on the treadmill,” Lucas posited, trying to shake me out of three decades of denial.

The “spastic” of spastic cerebral palsy comes from the Greek spastikos and means “pulling,” i.e., the “pulled” muscles in my legs that restrict my movement. “Pulled muscles!” I proclaimed. “Like tight tendons!” I contemplated giving myself the Twitter handle Spasticus. Like Spartacus, get it? Fortunately, Lucas intervened.

Spastic as a noun is an out-of-date slur for a person with CP. By the time I was a teenager, we’d shortened it to the much catchier spaz, a slight so common you can find it in the first entry of my seventh-grade journal, where I describe my brother as a “blast” and “overly energetic.” “He is a spaz, but that makes him both hilarious and rude/mean.”

So, what does it make me?

Contrary to college gossip, my leg never sailed the high seas in search of a whale, the prelude to a captain’s wooden appendage, but it has swung and lifted and climbed. It’s trotted along in theater tights and stood contrapposto at concerts. It’s survived surgeries and trembled beneath first kisses and fucked its way through the former Yugoslavia and bent in prayer. It even hobbled down the aisle toward a man with a mustache whom I’d topped after a Renaissance fest, in case you missed that part. It’s a wonderful leg and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it and my mother did the best she could in spite of having five kids and cancer and a husband who died of fucking ALS.

I mean, a leg—nothing could be less abstruse.

__________________________

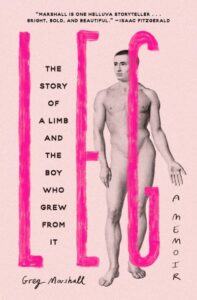

Excerpted from Leg: The Story of a Limb and the Boy Who Grew from It by Greg Marshall. Copyright © 2023. Available from Abrams Books.

Greg Marshall

Greg Marshall was raised in Salt Lake City, Utah. A National Endowment for the Arts Fellow in Prose, Marshall is a graduate of the Michener Center for Writers. His work has appeared in The Best American Essays and been supported by MacDowell and the Corporation of Yaddo. Leg is his first book.