How White Women’s Patronage of Black Artists Exposed Racial Fault Lines

L.S. Stratton on “Godmother” Charlotte Osgood Mason and Artistic Control During the Harlem Renaissance

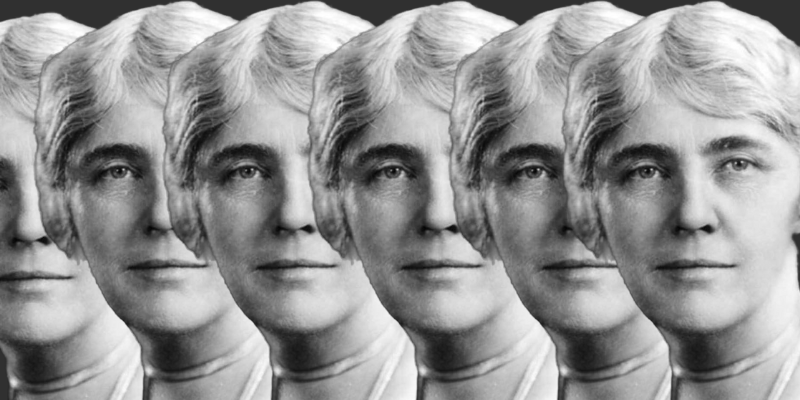

During the height of the COVID pandemic, I “doom scrolled” my way to an article that referenced Charlotte Osgood Mason, a Harlem Renaissance art patron who would become the inspiration for Maude Bachmann, one of the main characters of my gothic thriller, Do What Godmother Says. Mason was the patron of several Harlem Renaissance luminaries, including Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and Alain Locke, making me wonder why I’d never heard of her before. In high school, I’d even written a research paper on Hurston—one of my literary heroes—and her work, but I’d seen no references to Mason. After diving deeper into the complex story of Hurston and Mason’s relationship, I soon understood why.

Mason or “Godmother,” as she encouraged her many artists to call her, was a vanguard of her time who helped bolster a seminal American artistic movement. But she also burned several bridges along the way—including with her own artists, according to Miss Anne in Harlem: The White Women of the Black Renaissance by Carla Kaplan, a book I consulted frequently while writing my novel.

White patrons’ interest in Black art helped the Harlem Renaissance grow, but that interest could often be rooted in racist stereotypes.

Mason was a bold and opinionated woman who could be controlling and manipulative to the extreme. Her support for the Harlem Renaissance only had partly to do with her belief in the potential of individual artists or encouraging the acceptance of Black art by the existing establishment. She also did it because of the role these artists played into her eccentric spiritual beliefs.

There were several white women who served as patrons of the Harlem Renaissance, though Mason was probably one of the strangest and most toxic. While white male patrons like Carl Van Vechten and Alfred A. Knopf are more widely known, the influence of their female counterparts, with the exception of a handful, seems to have gone largely ignored or outright forgotten in contemporary discussions of the movement. (In some cases, such as Mason, probably deliberately.) Yes, Alfred A. Knopf Inc. published Harlem Renaissance authors Nella Larsen and Langston Hughes but it was Blanche Knopf who discovered them. Carl Van Vechten is credited for the surge of white interest in Harlem Renaissance artists, but it was his wife, Fania Marinoff, who vetted the guest lists and hosted the exclusive parties where Black artists and white publishers, agents, journalists, and patrons networked.

*

The white female patrons of the Harlem Renaissance circumvented the gender constraints of their time period, especially as white women in high society. They rubbed shoulders with the leading Black thinkers and artists in the movement and wrote checks along the way. Kaplan said that in Harlem, these women could experience the freedom and exert the power and influence that would never be afforded to them in the white, male-dominated world that they usually navigated.

One example was Annie Nathan Meyer, the patron, author, vocal anti-suffragette and playwright of Black Souls, a “Negro play” that was considered controversial for its time for tackling the themes of racism, lynchings, and interracial sexual relationships.

A descendant of one of the first Jewish families to settle in New York City in the 1600s, Meyer grew up in a wealthy family that saw its fortunes change with the financial crash of 1873. Self-taught and studious, in 1885, Meyer enrolled in the Columbia College Collegiate Course for Women at the then all-male Columbia College. The program allowed women to sit for examinations for all undergraduate degrees but did not allow them to attend the lectures that would prepare students for the examinations. Meyer rightfully pointed out this practice was ridiculous.

She pushed for the creation of Barnard College, a women’s liberal arts college affiliated with Columbia College and named after Columbia President F. A. P. Barnard. At Barnard, women could finally pursue the education that had been denied to them at Columbia. (Coincidentally, Meyer also championed and helped raise scholarship money for Zora Neale Hurston—making Hurston the first Black woman to attend Barnard.) Though Meyer was one of the Barnard trustees until her death, she didn’t feel she was rightfully acknowledged as the college’s founder, suspecting the affront was rooted in anti-semitism. But she did not encounter this same anti-semtisim while working with the Black community in Harlem.

“For Jewish women like Meyer,” Kaplan observed in Miss Anne of Harlem, “there may have been particular temptations associated with activist work in Harlem. Jewish activists might become ‘white’ people in Harlem, when many had never before experienced themselves as ‘whites’ in larger American culture.”

Both Black critics and artists applauded Meyer’s production of Black Souls, despite its 10-day run, which was far shorter than Broadway productions she’d written in the past. Hurston, Harlem Renaissance author Jessie Fauset, former executive secretary of the NAACP James Weldon Johnson, and his NAACP successor Walter White all vocally supported the play.

Meyer would later say her play gave her something “worth living for.”

*

White patrons’ interest in Black art helped the Harlem Renaissance grow, but that interest could often be rooted in racist stereotypes, according to historian Casey Nelson Blake in his Columbia University e-seminar, The Rise of Consumer Culture. Patrons like Van Vechten “often presented the achievements of Blacks as deriving from the inherent primitivism or emotionalism of African American culture, suggesting that whites should turn to Black culture in order to free themselves from whatever remained of the Victorian constraints of their parents and grandparents.”

This subject of control of Black art is probably why so many white patrons like her have been forgotten.

Mason was of like mind, believing this “primitivism” could be White America’s literal salvation. Her fetishization of Black culture started well before the Harlem Renaissance, fomented by her husband, Dr. Rufus Osgood Mason, friend to the Rockefellers and one of the founding fathers of parapsychology and hypnotherapy. The doctor and his wife believed in the spiritual superiority of the so-called “primitive cultures” of the Native Americans and Africans. Charlotte Osgood Mason even claimed to have had visions of a “flaming pathway to Africa” that, if followed, could help cure the spiritually bereft white American society. She would become obsessed with creating that flaming pathway before she died, envisioning her Black artists as her building crew while she would take the lead and be the architect.

But “taking the lead” meant having an iron grip on her artists’ work and their lives. Mason not only wanted to give feedback on their work, but she also wanted to control where and when they submitted it. Her contracts with some of her artists stipulated that she owned the work they produced in perpetuity. She ordered Langston Hughes to write to her daily, according to Patronage and the Harlem Renaissance: You Get What You Pay For by Ralph D. Story. She chose the books he read, the music he listened to, and the plays he saw. Hughes chafed so much under her constraints that their relationship ended after only three years. Kaplan said Mason’s contract with Hurston stated that she owned Hurston’s anthropological research material, from the documents to recordings. Mason kept Hurston’s research in a locked safety deposit box to which Hurston did not have a key. Mason also expected full accounting of how her patron money was spent, even making Hurston write itemized lists of all her grocery purchases so they could be reviewed. The patron made some of her artists keep journals and they had to read their journal entries aloud to her.

Though Mason is the most extreme version, this subject of control of Black art is probably why so many white patrons like her have been forgotten. Though they provided the funding and the buzz, they did not supply the labor or the seeds of creativity that came from the African American culture they admired, adapted, and, in some cases, fetishized. Money could buy them influence, but not ownership. And with the stock market crash in 1929, even the well of money that had been pumped into the Harlem Renaissance by its numerous patrons began to run dry, according to Story. The Urban League, which held the annual Opportunity magazine awards banquet that highlighted Renaissance authors like Hurston, held its last gala in 1933 after concluding “the money and interest to sustain the tradition were lacking.” Worse, like many artistic movements, the Harlem Renaissance and its artists were no longer in vogue. By the 1930s, Harlem no longer had its “edge” for the white patrons who had flocked there in the 1920s. They had other artistic movements to embrace or, in the case of Mason, lost interest in supporting the arts entirely when they couldn’t get their artists to behave the way they wanted.

__________________________________

Do What Godmother Says by L.S. Stratton is available from Union Square & Co.

L.S. Stratton

L.S. Stratton is an NAACP Image Award-nominated author and former crime newspaper reporter who has written more than a dozen books under different pen names in just about every genre from thrillers to romance to historical fiction. She currently lives in Maryland with her husband, their daughter, and their tuxedo cat.