How White Supremacists Used Mardi Gras to Enforce Racial Division

Edward Ball on Reconstruction-Era Carnival in New Orleans

The stage is arranged, the Ku-Klux pageant begins.

On March 4, 1867, a Monday at 10 am, 2,000 firemen jostle left and right into parade columns on Canal Street, near the levee of the river. Their costume is full dress uniform. Marshals from the Firemen’s Charitable Association yell the lines into order, and the procession moves: 35 fire companies, 33 marching bands, hundreds of horses, two dozen fire trucks. The firemen carry banners, horns, hoses, and ladders prettily draped with flowers.

Constant Lecorgne appears somewhere in the middle of the long snake of a march. The 85 men of Home Hook & Ladder are the eighth company in line, behind the 62 men of William Tell Hook & Ladder and in front of the 72 of Philadelphia Engine Company, whose draft horse—black and shiny—is named “Nig.” A rustle of laughs whenever the driver yells, “Git, Nig!”

Newspapers run pages of detail, description, and praise. A reporter clocks it: 55 minutes for the parade to pass.

Wending from downtown to Jefferson City and back, the firemen’s march is a two-mile-long victory parade. “New Orleans turned out en masse to greet and crown her heroes,” says a reporter. One paper estimates the crowd on the banquettes to number 100,000. If true, it is half the population of the city. Reporters say nothing about black spectators. African Americans, now a third of the population, seem conspicuous in absence.

The big crowd has something to do with fires, I think, and something with events at the Mechanics Institute. The en masse want to thank some of their fighters.

Home Hook & Ladder is “uniformed beautifully, in blue and white, with Old Stonewall, the company’s noble horse, walking proudly on, feeling monarch of all he surveys,” says a witness. At the end of the day, some firemen move on to banquets and dancing, others to receptions and barbecues. But the heroes and their fans have no rest between drinks, because the following day, Tuesday, is Mardi Gras.

To imitate the black race proves the gulf between the white and black worlds, a gap that must be shown again and again.

People say the culmination of Carnival season, coming March 5, is late this year. It is the fault of the stars. Mardi Gras, Fat Tuesday, always falls forty days before Easter Sunday, and the date of Easter shifts with the astral calendar in logic no one understands.

The firemen who crowd the streets on Monday are out again Tuesday. But instead of marching, they carouse, many with their families. While the firemen’s parade was white, Carnival is black and white. Mardi Gras lowers the walls of difference and hostility between tribes, or at least so it is said by both species that crowd the streets.

On the big day, the Lecorgnes are probably in the mix with everyone, probably masking, costumed as one thing or another. Many people put on a character. Men and women dress as animals or plants, archangels or demons, princes or paupers, roles from a play or from folklore. If Constant and Gabrielle follow a common pattern, they drift from street to street with their children, everyone in an outfit, stopping for food and a laugh on a friend’s porch, or kissing to greet before sitting to drink at some sister’s silver-strewn dinner table.

It is common for a white woman or man to dress as one of them, les nègres. Probably several thousand whites wear blackface and dress as they think African Americans might, or should. To “black up” is a reassuring custom. To imitate the black race proves the gulf between the white and black worlds, a gap that must be shown again and again.

When whites pretend to be black, they do so on stage as well as in the street. It is the minstrel troupe that shows the Carnival crowds just how to play at color. Minstrelsy is the most popular of all forms of theater, from Louisiana to Atlanta, New York to Chicago. It is the nation’s schoolhouse for “niggering.” Everyone learns tricks from minstrel men—the loud dressing, the shucking and shuffling, the blackface and black talk, the singing like howling, all those things colored people do. All those things make superb material for masking at Mardi Gras. Whites pretend to be black as though pretending to be an animal or a character in myth.

I wonder whether the six Lecorgne siblings, Constant and his brothers and sisters, are blacked up. Maybe Constant wipes grease or the ash of burned cork on his face and pulls on a ragged pair of pants. It would not surprise me, and he would have much company.

On Mardi Gras, whites can black up, but black people do not dress as crackers at Carnival. To do so might be dangerous. It might cause trouble among the considerable number of crackers who do not see themselves as ridiculous, or like animals. It might bother the large number of whites who do not have a sense of humor.

Maybe Gabrielle and Constant are in light costume, with only a mask on the face. Constant might be wearing a plain “domino” mask, which covers the eyes and nose but leaves the lower half of the face exposed. The domino mask is the least disturbing of Carnival disguises. But it is possible that Constant wears a “moretta” mask, the one that is menacing to look at. Moretta masks cover the whole face, except for the nostrils and eyes. They are blank of expression and held in place by a button clenched between the teeth. With its empty coldness, and because it prevents the wearer from speaking, the moretta causes the most discomfort of any mask in a room. Most are entirely black. To wear one is to broadcast pure and monstrous blackness.

The six Lecorgne siblings—Yves of God, Ézilda, Constant, Joseph, Aurore, and Eliza—do not carouse with rich and pretentious whites. They are family people, parents in their thirties and forties, and they have drifted down from their old perch among the slaveholding elite. Their social circles are more plain, except for the starchy Yves of God, who keeps finer company. The Lecorgnes mask with hoi polloi, more common whites. They have little to do with the businessmen and moneychangers who float in the city’s richer class. Those families, or some of them, are pulled toward one Carnival group, to which the Lecorgnes do not belong, the Mistick Krewe of Comus.

A few businessmen set up “Comus” before the Civil War. (In the same love of alliteration that gives birth to the word “Ku-klux,” they coin the word “krewe.”) The Krewe of Comus takes its name from John Milton’s play Comus, in which the named character is the debauched god of revelry, who captures a woman, brings her to his palace, ties her to a chair, and tries to seduce her with flourishes of a large wand. (He fails.) The Krewe of Comus puts on a nighttime parade, a procession that moves by torchlight on Mardi Gras, with costumes and music and rolling floats decorated with scenery—tableaux roulants. It is a parade that ends in the ballroom of the Varieties Theater, on Gravier Street, where the Krewe puts on a bal masqué, masked ball, and members perform a tableau, a silent bit of costumed theater.

It is all so tasteful and restrained. While most of Mardi Gras, both black and white, is louche and wanton.

Comus is bigger than the heads and wallets of the Lecorgnes. I imagine that Constant and family, like many in the city, watch on Mardi Gras night as the masked men of Comus guide their mule-drawn tableaux along St. Charles Avenue toward the theater. The Lecorgnes watch, and they wave. On one float, Constant might see a familiar face. Or he might see a familiar beard, because the face itself is masked.

It is the face of Henry Hayes, sheriff of New Orleans, a man with a foot-long black beard. Hayes is the sheriff in the Mechanics Institute massacre, the man who deputizes ex-rebels to assist in the killing. He appears on a Comus wagon draped in a robe, mask, and half hood, an outfit that is becoming common Carnival gear. The hands of Henry Hayes are two of the bloodiest in the city. It is coincidence, of course, that the sheriff is president of the Mistick Krewe of Comus. Constant and Gabrielle wave as the tasteful and restrained leader of Mardi Gras revelry trundles past.

__________________________________

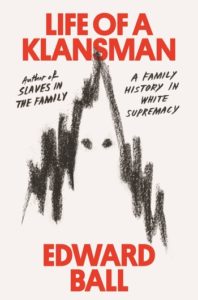

From Life of a Klansman by Edward Ball. Used with the permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2020 by Edward Ball.

Edward Ball

Edward Ball’s books include The Inventor and the Tycoon, about the birth of moving pictures in California, and Slaves in the Family, an account of his family’s history as slaveholders in South Carolina, which received the National Book Award for Nonfiction. He has taught at Yale University and has been awarded fellowships by the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard and the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center. He is also the recipient of a Public Scholar Award from the National Endowment for the Humanities.