How White Parents Shirk Their Moral Responsibility to the Common Good Under the Cover of Responsible Parenting

Courtney E. Martin on the Many Ways of Asking the School Question

Thirteen Ways of Asking the School Question (after Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”)

Where do we want to send our kid to school?

How does that choice align with or depart from our values?

Does that even matter? (I mean, does integration actually work?)

What is a school?

What is education for? What are we afraid of?

Who are we—as parents, as (white) people—and what does this choice say about that?

(To us? To everyone else? To Maya?) Where will Maya learn and feel loved?

Where do Oakland kids learn and feel loved?

*

I’m filthy with friends and surrounded by caring neighbors. I have ten women whom I can text right now to ask which diaper cream they think actually works (Weleda) or whether earthquake insurance is worth it (nah). So far, I haven’t found one White friend who is seriously considering our neighborhood public school.

Maybe the repulsion to Emerson is the result of living in the shadow of Silicon Valley and the comparison it invites. Even if we’re economically secure by any rational calculation, even if we’re rich, for that matter, we have a way of feeling always in danger of becoming noncompetitive. What if we are unable to buy a house or get our precious children the most humanizing, beautiful educational experience possible? What if we are actually ordinary or, worse, helpless? Or as philosopher Alain de Botton writes in Status Anxiety, “Amid such uncertainty, we typically turn to the wider world to settle the question of our significance.”

Every person has to come to terms with—even if just for themselves—the gap between what they believe and how they live their lives.

The wider world, for White and/or privileged Oakland, is economically freakish. While the average worker in the city makes a bit over $40,000, the average Facebook employee makes well over $200,000 a year, with a luxurious suite of benefits (at least luxurious in a country that has no federal paid family leave). When you sit in birth class beside someone who is not only getting paid six times what you are but will enjoy six full months off work, paid, while you have no paid leave at all, it’s hard not to feel envious and small.

My friends with little kids are too stressed and too wrapped up in their own feelings to entertain any but the most strategic questions. But whenever I bring up school choice and racial equity with White parents who have older kids, a resigned malaise settles on their faces, and they almost always sigh audibly. These parents of pimply, emotionally manipulative teenagers appear to see me, the parent of ratty-haired, emotionally raw toddlers, as well intentioned but also in need of humbling. Just keep your kids off drugs, they seem to be saying with their eyes. That’s enough work for one parenting lifetime.

At a potluck dinner, I bring up with a Black friend my conflict over enrolling Maya at Emerson. I’ve been listening to This American Life episodes on the anniversary of Brown vs. Board of Education by the brilliant journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones. I’ve been thinking about integration. And my friend says, “Don’t send your kid to a shitty school on my account!”

The record scratches in my brain. I want to ask her a million questions, but this is not the time for me to do my usual annoying thing of being way too serious at a really fun party. My friend’s words echo in my head for weeks afterward—unprocessed, so powerful.

I flash back to anxious preschool tours. I can’t help but wonder: Are all those White parents going on all those tours actually part of the problem? Is the real issue not that parents of color should be on the tours but that school tours shouldn’t be a thing at all? Are these anxious White and Asian-American parents the ones who are wrong, while everyone else is just trying to live a decent life?

Every person has to come to terms with—even if just for themselves—the gap between what they believe and how they live their lives. And if you happen to be a parent, the gap can feel particularly wide and meaningful, the rationalizations even more garbled and urgent. Ultimately you’re not answering to just your own conscience but to your children, too. They will want to know—they might already want to know—why you did what you did. Why send them to this school? Why make the sometimes soul-crushing effort to get them into clean clothes and in these particular pews on a Sunday morning? Why live in this neighborhood? Why befriend these people but not those? Why care so deeply about certain rules and let other things go? Kids ultimately care, not just about how you shape them but also how your shaping of them shapes the world.

I suspect that White economically privileged and well-intentioned people have shirked our moral responsibility to the common good for decades under the cover of responsible parenting. In a time of eroding public institutions and soaring economic inequality, we have normalized private solutions whereby our children won’t have to endure the most broken American systems—public education, health care, the courts. By doing so, we’ve inadvertently created one of the country’s biggest problems: increasing and unconscionable inequity. We act mystified by this inequity, all the while propping it up with our choices.

Or as the poet and essayist Hanif Abdurraqib, puts it, “Not everything is Sisyphean. No one ever wants to imagine themselves as the boulder.”

____________________________________

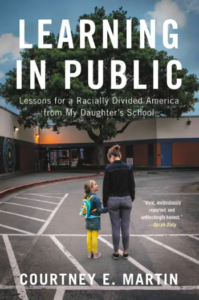

Excerpted from Learning in Public. Used with the permission of the publisher, Little, Brown. © 2022 by Courtney E. Martin.

Courtney E. Martin

Courtney E. Martin is a writer living with her family in a co-housing community in Oakland. She has a popular Substack newsletter, called Examined Family, and speaks widely at conferences and colleges through out the country. She is also the co-founder of the Solutions Journalism Network, FRESH Speakers Bureau, and the Bay Area chapter of Integrated Schools. Her happy place is asking people questions. Learning in Public is her fourth book.