How Walking Shaped Simone and Hélène de Beauvoir's Art and Thought

Annabel Abbs-Streets on the Idiosyncratic Way the Beauvoirs Hiked Through the World

Most of us are familiar with Nietzsche’s words, “All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking” or Thoreau’s famous line, “The moment my legs begin to move my thoughts begin to flow.” And so we assume that walking, somehow, oils the brain. We move our feet in a forward direction, and our brain simultaneously begins to crank out new ideas.

But, as I discovered when I walked in the footsteps of legendary feminist Simone de Beauvoir, this is far too simplistic. Writers, artists, thinkers and musicians, walk for very different reasons, in very different ways, and with very different outcomes.

Simone’s hiking was nothing like Nietzsche’s “walking” or Thoreau’s “sauntering.” She marched. Like a machine. Her mind empty of all thought. And without (so she said) generating a single idea.

But as I walked her paths, I began to understand that Simone’s claim wasn’t quite accurate. Instead, her walking fuelled her intellectual practice in a peculiarly idiosyncratic and female way—a way thrown into sharp relief when compared with the walking practice of her artist sister, Hélène.

A particular story haunted me. It was an account left by Simone of one of her earlier walks, just as she was learning to trust her feet, her body and her map-reading skills. Simone had left Paris and was teaching in a girl’s school in Marseilles where she had no family or friends. Her younger (only) sibling, Hélène, arrived to stay for a few days.

Simone’s hiking was nothing like Nietzsche’s “walking” or Thoreau’s “sauntering.” She marched. Like a machine.

It was the end of November and snow already lay on the ground, but Simone was determined to induct her little sister into the delights of hiking. Despite neither woman having the proper walking kit, they headed off, in espadrilles and dresses, with baskets of bananas and buns swinging from their wrists.

The first walks were a success, at least as far as Simone was concerned. Hélène uncomplainingly kept pace, despite having no experience of long-distance walking and regardless of the “agonizing” blisters blooming on her feet.

But the next walk didn’t go so well. Two hours in, Hélène became feverish and began shivering uncontrollably. Instead of accompanying her little sister home, Simone decided to leave her in a “gloomy” pharmacy, to wait several hours for the return bus to Marseille. When Simone got home that evening, tingling from the vigor of her walk, Hélène was in bed with raging flu.

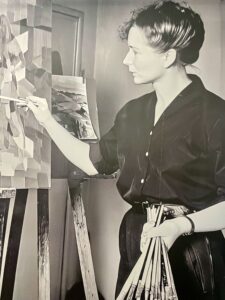

Simone and Hélène’s de Beauvoir

Simone and Hélène’s de Beauvoir

This stunning display of self-centered, single mindedness was the first indication that walking in Simone’s footsteps might be more complicated than I had imagined. Simone, it appeared, wasn’t your usual country hiker. Nor was she a drifting, contemplative Thoreau or an idea-spewing Nietzsche. She was a ruthless walker on a dogged mission of self-discovery.

In fact, since arriving in Marseille, Simone had developed a fanatical walking habit. She bought detailed military maps of the local terrain and studied them for hours, choreographing routes, scrutinizing contours and examining bus and train timetables.

With the precision of an army general, she used her empty evenings to map out lengthy hikes that she called “works of art.” She had two days off each week—Thursday and Sunday. On both days she rose at dawn and hiked her “works of art” manically until nightfall, usually alone, often covering twenty-five or thirty miles in a single day, regardless of the season, altitude or weather. And yes, wearing espadrilles and a dress.

In her letters to Sartre, Simone boasted of how fast she walked, of how high she climbed, of how little fatigued she was and—more surprisingly—of how few thoughts crossed her mind. She may not have “thought” much, but her walking deeply and profoundly affected her identity, her self-esteem, and her work.

Today, we’re familiar with the idea of “strong body, strong mind.” No one questions a woman pumping iron to strengthen her self-esteem, her chutzpah, her audacity. But a century back such a notion would have been ridiculed, particularly for a woman without any history of sporting prowess.

And yet it’s clear that Simone’s strenuous hiking—which involved climbing in and out of crevices, scrambling over scree, leaping walls, lugging a weighty backpack for weeks on end and sleeping on benches—were an attempt to build the mental stamina necessary for her work-to-come. Her hikes allowed her to recast herself, from the frail, weak female she had been raised as, to a woman of fortitude and independence.

In her memoir, she recalled that, after this period of sustained hiking, “I no longer despised myself.” In her letters, she explained that her “crazy walking” taught her “to live by myself, to support myself, not to be dependent on anyone in any way.”

As I walked Simone’s routes, I forgot about the little sister she had so callously dumped. But later, while trudging the hills of the Luberon in France, I returned to Hélène. There is no record of the pair ever hiking together again.

And yet the callousness displayed by Simone wasn’t personal (she and Hélène were close all their lives): Simone just had her own way of walking. Later, she dumped friends and lovers, anyone who fell sick was instantly left behind to fend for themselves. Anyone who walked too slowly, or without her stamina, was mercilessly dropped. Simone waited for no one.

This refusal to deviate from her “prepared program” (as she put it) or to “envisage the possibility of disruption,” or “to admit that life contained any wills apart from my own” was, she confessed, “very deep-rooted.” Sartre called it “schizophrenia.” She called it “optimism.”

And yet walking became an essential ingredient in Simone’s intellectual and creative practice. Unlike contemporary writers who often describe walking as a helpful space in which to think through plot and character, or just a place in which to rest their churning minds, Simone walked to test herself.

While Simone was rigorously testing the physical strength of her body and the emotional resilience of her mind, Hélène used her walks to look, to observe, to see deep into the heart of things.

In the ravines and valleys, through the forests and over the hills of some of France’s remotest and wildest areas, Simone hiked without any of the trappings we consider essential today. No protein bars, no waterproofs, no mobile phone, no GPS. Instead, she walked to test her ability to withstand exhaustion, altitude, terror, silence, aloneness.

She walked to challenge her fears, her sense of time and space, and the capabilities of her body. And when fellow ramblers suggested she walk with them, without hitching rides, and in the correct footwear, she ignored them. Because she also walked to challenge the rules—exactly as she later did in her writing.

Even her exhaustive navigational planning was an attempt at the independence she longed for. Women weren’t taught or encouraged to read maps because they weren’t supposed to be in the wilds, alone. A careful reading of Simone’s ground-breaking The Second Sex makes it abundantly clear that this relentless testing of her mind and body—as she hiked—precipitated many of her most brilliant ideas.

In spite of being abandoned by her sister mid-hike, Hélène also became an avid walker. But Hélène showed me a very different way of walking. While Simone was rigorously testing the physical strength of her body and the emotional resilience of her mind, Hélène used her walks to look, to observe, to see deep into the heart of things. For Hélène, walking was a more obviously creative act, as made evident in her paintings.

Hélène’s de Beauvoir painting

Hélène’s de Beauvoir painting

Hélène’s story has been lost beneath the vast shadow of her sister’s better-known and more closely-recorded story. Today Hélène’s paintings are in the collections of Paris’s Centre Pompidou, Florence’s Uffizi Museum, Oxford University, France’s Musée Würth, the Erstein Museum of modern and contemporary art in Strasbourg, and the Royal Library of the Netherlands. The first British exhibition of her work has just opened in London (on until 30 March at the Amar Gallery).

Hélène is lauded as an early feminist and environmentalist. In fact, Hélène (who was two years younger than Simone) claimed to be a feminist before her more famous sister.

Neither aspired to be the homemaker their parents expected of them. Neither had children. Both were marked by watching the circumscribed life of their housewife mother and by the oppressive smallness of their shared childhood.

The cramped bedroom of their girlhood—in which they had to climb over each other’s rammed-together beds in order to exit—precipitated a mutual, life-long appreciation of vast open spaces and of physical movement. From their tight little bedroom, they glimpsed an infinitely more exciting world. The girls grew up in Montparnasse, where their parent’s apartment overlooked the glittering lights of the brasseries famous for their jazz-age celebrity clientele.

Here, the sisters waited for their parents to go out in the evening, then crept onto the balcony and watched the exotic, unconventional artists coming and going: Modigliani, Matisse, Picasso, Marie Laurencin. Later, Hélène recalled them as coming “from a world so close, yet so inaccessible.”

This dual aspect—a confined, oppressive home atmosphere which looked directly into a magical world of liberty and possibility—created an impetus in both daughters to escape the world of their parents, to live freely, and on their own terms.

But while Simone’s grueling hikes became fodder for her feminist and philosophical ideas, Hélène’s walks opened and nurtured her visual imagination. Many of Hélène’s paintings (she created over three thousand in her lifetime) are carefully observed landscapes—mountains, valleys, rivers, the ocean—using minimal paint applied in deft spare strokes so that they feel as light as soap bubbles.

Her observations of the world around her wouldn’t have been possible if, like her older sister, she had been preoccupied with speed, duration, height and overcoming physical and navigational challenges. At a 2017 show in Italy the curator noted that her paintings “represent visual glimpses of the landscape…discovered during her walks, bringing back to the canvas a nature transformed into an almost abstract and dreamy impression with mythological connotations.”

Walking in nature became an essential element in both women’s attempts to simultaneously escape and become. Hélène, however, was meticulously observing—lines, shapes, colors. She also sought out scenes worthy of painting, particularly those involving women at work. Indeed, Hélène drew repeatedly on the material she found on her ambles.

Reflecting on the different ways in which both women used walking to reinvent themselves and as part of their respective artistic practices made me reflect on the many ways in which writers and thinkers have always walked. There is a rhythm to walking that seems to unlock something in the mind—hence the oft-quoted words of Thoreau and Nietzsche. But there are dozens of other reasons and ways to walk as part of one’s creative practice.

For painters like Hélène, walking was less about rhythm and more about being in close proximity to the colors, tones and forms they later replicated on canvas.

The anthologist-of-walking Duncan Minshull suggests that writers, philosophers, painters and musicians have always headed off somewhere “because going for a walk actually helped form their work.” Sometimes this “help” arrived in unexpected ways.

Minshull gives the example of Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, who wandered the streets of Copenhagen in order to meet and talk to fellow pedestrians. It was the conversations he had and the human connections he made while walking that nourished his philosophical ideas.

Musicians walk, says Minshull, because the rhythm is often conducive to melody making: Beethoven famously walked the Vienna Woods, claiming that as he wandered amongst the trees, new tunes simply came to him. Poets often walk for the same rhythmic reason: Imtiaz Dharker suggests wearing solidly heeled shoes so that our steps resemble a clearly audible metronomic beat. Words come as our feet beat out a rhythm on the pavements.

For painters like Hélène, (and Gwen John or Georgia O’Keeffe, whose trails I also followed), walking was less about rhythm and more about being in close proximity to the colors, tones and forms they later replicated on canvas. For Hélène, this proximity to nature and wildlife—flowers and animals appear in dozens of her paintings, drawings, and engravings—also led to her early environmentalism.

As she walked, she noticed the dwindling connection between humans and the countryside. It distressed her, and was to become the subject of several of her paintings.

Hélène and Simones’ relationship was complicated. Simone supported Hélène all her life, paying for her first studio, painting materials and plane tickets to the far-flung cities where Hélène’s work was exhibited. And yet Hélène envied Simone’s success.

Despite painting every day, all her life, Hélène’s work didn’t receive the attention that Simone’s did. Days before she died, her last words—to Claudine Monteil who had befriended both of the Beauvoir sisters and later wrote about them—were: “Do you think my paintings will still be seen when I am dead? Do you think they still remember my paintings in Paris?” She wanted to be remembered, just as her sister was—and is.

I like to imagine the two sisters on a long hike, untangling the complications of their relationship. But this might be too fantastical. A more realistic image would be Hélène crouched curiously over a flower or butterfly, with Simone on the skyline, marching ever upwards, her limbs burning. Two ways to walk, yielding two very different outcomes, and revealing two very different sisters.

______________________________

Windswept by Annabel Abbs is available via Tin House.

Annabel Abbs

Annabel Abbs-Streets is the author of Windswept: Walking the Paths of Trailblazing Women (Tin House), out now in paperback.