How W.H. Auden Made Austria His Adopted Home

Michael O'Sullivan Follows the Famed British-American Poet Across Europe

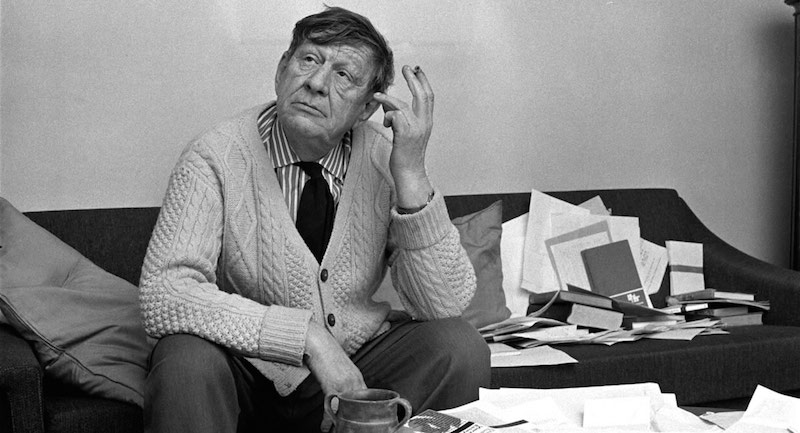

W.H. Auden has become so central to my life over the past forty years that there never appears to have been a time that it could have been otherwise. He is, for me, a talismanic touchstone. My conversation has become so peppered with quotes from his work and about his life that I am frequently asked when I first met him. I was still at school in Ireland when he died in 1973. His niece married an Irishman, and the poet’s great-niece was at Trinity College Dublin with me. However, Auden, the great peregrinus, a visitor to nearly thirty countries, never set foot in Ireland.

My English teacher and mentor, T.F. Lane, first made me aware that Yeats and not Ireland featured more in Auden’s poetry. “Ireland has her madness and her weather still” is the nearest we come to an Audenesque Hiberno travelogue. He enjoyed telling how immensely proud he was of writing a poem in a complex Gaelic meter. He also demonstrated an extraordinary knowledge of contemporary Irish politics when he came to write “The Public v. The Late Mr W.B. Yeats” in 1939. It was a time when he was beginning to question the influence of Yeats on his work and to consider also, Yeats’s politics which he found distasteful.

Auden significantly influenced modern Irish poets, including Patrick Kavanagh, Seamus Heaney, and Derek Mahon. In Finnegans Wake, he appears as a terse footnote in which Joyce acknowledged the young poet’s claim to Nordic ancestry when he wrote, “I bolt that thor. Auden.” He read Finnegans Wake soon after its publication and, like Evelyn Waugh, was not especially taken by it. However, it did have a limited influence on aspects of “The Age of Anxiety.” In an interview with The Paris Review, he offered this view on the work: “Obviously, he’s a great genius—but his work is simply too long. Joyce said that he wanted people to spend their life on his work. For me, life is too short and too precious. I feel the same way about Ulysses. Also, Finnegans Wake can’t be read the way one reads ordinarily.” He had a brief youthful flirtation with the mystical verse of Yeats’s friend George Russell (AE), and he brilliantly described Oscar Wilde as “a phoney prophet but a serious playboy.” The Ascent of F6 was produced at Dublin’s innovative Gate Theatre in 1939. There, with those flimsy associations, the possibility of any more substantial links between Auden and Ireland ends.

In honoring Auden’s memory, I came to enjoy my first meaningful role in the Audenworld.

My own connection to Auden and his world began at Trinity when I chose him as the subject of my postgraduate work in the English Department. Charles Osborne’s biography of Auden had just been published and serialized in The Observer. I recall reading the first extract in The Observer on a wet Irish Sunday in March 1980. I was fascinated by the details of a life which were largely unknown to me and many others, and I found them an absolute revelation, if not indeed something of a sensation. However, that book was soon to be eclipsed by the biography Humphrey Carpenter was about to publish.

“Burn my letters,” Auden exhorted his friends by appealing to his estate to publish press notices with this request after his death. His literary executors did as they were requested. Fortunately, few of his friends acquiesced to his wish, and most of those who Humphrey Carpenter contacted gave him access to their correspondence with Auden.

Throughout his life, he railed on about his abhorrence of the idea of someone writing his biography. “A writer is a maker, not a man of action” was the oft-repeated mantra. He claimed that reading a man’s personal letters after his death was as impertinent as reading them while he lived. As in so much else, he was a mass of contradictions. While waiting in his tutor’s rooms at Oxford, he casually picked up letters from his desk and began reading them. When his newly appointed tutor, Nevill Coghill, arrived, Auden told him a page from a particular letter was missing and asked him where it might be found. So, while not wishing other people to be tourists in his life, Auden had no difficulty making occasional visits to the lives of others.

A letter from me to Humphrey Carpenter brought a most courteous, if slightly guarded, reply. I had been given a research award to look at Auden’s papers and related material at Oxford and thought it a good idea to contact his biographer, who lived in the city. We arranged to meet at a public house much frequented by Oxford students. After a few ice-breaking drinks, my youthful enthusiasm for Auden struck a chord with Humphrey, and he invited me home to lunch with his wife and family. Only after much convivial banter did I realize, to my absolute surprise, that the real purpose of the invitation was to show me the vast quantity of material he had amassed during the course of his research for the Auden biography.

To my even greater surprise, when I was leaving, he handed me a large box containing much of that material, saying, “This should help you with your research.” I then moved through a sweltering Oxford with this weighty gift, quietly in awe of my generous benefactor and thinking how lucky Auden was to have had such a man as the chronicler of his life. It was the beginning of one of many friendships initiated through my burgeoning Auden obsession and which brought me into the direct path of many of his friends.

An old friendship and some new ones also brought me to Austria and towards a more tangible connection to Auden’s Austrian life. In 1982 an Irish scholar and writer, Patrick Healy, introduced me to the American artist Timothy Hennessy, who was organizing a major exhibition of his work in Paris as a tribute to James Joyce. It was part of the centenary celebrations of Joyce’s birth. A central part of that exhibition was Patrick Healy’s reading of the complete text of Finnegans Wake. On the sidelines of that event, I met the then Vienna-based linguist and translator Lise Rosenbaum. She told me of the existence in Vienna of The International Auden Society, founded by Peter Müller of the Bundesdenkmalamt and the author and journalist Karlheinz Roschitz.

A letter to Peter Müller brought a reply inviting me to stay with him in Vienna. Within a week of arriving, the idea of an exhibition and symposium to mark the 10th anniversary of Auden’s death, which fell the next year, was born. Müller was an extraordinary man, and though he travelled extensively in the rarefied world of both the Austrian intellectual and aristocratic set, he never lost touch with his roots in a small village in Lower Austria. He possessed a charm and self-assurance which left him equally at ease in a castle or cottage. I remember him bringing me to see the blood-stained uniform of the murdered Archduke Franz Ferdinand when this relic of Sarajevo was being inspected by his office. For a moment, we were alone with the glass lid lifted. We looked at each other and at the uniform, and then he suddenly said, “Go on, touch it, touch all that terrible history.” I declined his offer. He brought me on many a pilgrimage to places and people associated with Auden’s Austrian life. As Auden was just ten years dead, many people in Austria remembered him, and Peter Müller knew all of them.

But none would have as much influence on me personally or on my understanding of W.H. Auden as his friend, the exceptionally intelligent woman, Stella Musulin. She was born Stella Lloyd-Philipps to an old landed gentry family in the ancient Dale Castle in Pembrokeshire. Her marriage into the Austrian aristocracy brought the moniker Baroness Stella Musulin de Gomirje. However, she wrote extensively, cleverly, and with piercing insight on a polyglottal range of subjects as plain Stella Musulin.

Austria, Auden’s final resting place, his adopted homeland, and arguably where he was happiest during his lifetime, continues to be the country where he is most honored. In honoring Auden’s memory, I came to enjoy my first meaningful role in the Audenworld, which, happily and fortuitously, brought me into contact with some of his closest friends, especially Stella.

Peter Müller was the catalyst in those years for all things celebratory in relation to Auden in Austria. It was while staying with him at his flat in the Schlosselgasse in Vienna in 1983, a moment which I can only best describe as high “camparama,” that Müller’s notion arose that I should organize an exhibition and symposium to mark the 10th anniversary of Auden’s death, which fell in September of that year. He was showing me a crystal wine flagon and glasses from his collection, which were once part of a suite made for Empress Maria Theresa, and at that moment, he said, “Let’s fill these up with wine and toast the idea of the Auden exhibition.” I like to think that such high camp style would have amused Auden, who was not averse to the odd incursion into the world of high camp himself.

Once the heady intoxication of the wine from Maria Theresa’s wine accoutrements had worn off the next day, I was faced with the reality of honoring a commitment to Peter Müller—who took such matters most seriously—to give Vienna the most significant ever public celebration of Auden’s life and work. Vienna was accustomed to hosting impressive arts events, and I soon realized that what was expected was something grand. Within a week, Müller had arranged a meeting with the director of the Lower Austrian Society for Art and Culture, Dr. Eugen Scherer. This organization was the cultural arm of the Lower Austrian government, and they had under their control one of Vienna’s premier public art spaces, a gallery in the Kunstlerhaus, which was near some of Vienna’s major cultural icons—the Konzerthaus, the Musikverein, the Secession, and the State Opera House. Eugen Scherer was immediately taken by the idea and almost instantly guaranteed the not-inconsiderable funding it would take to assemble the celebration of Auden on the scale that we now had in mind.

In principle, we all agreed that the event could not be a dry academic affair, and it would have to be attractive to a wide parish, not just to Auden enthusiasts. A strong visual element was essential; there would be music, film, commissioned artworks, audio works, and, of course, the Auden texts in their many varied forms. In tandem with all this, it was agreed that a symposium of Auden scholars would deliver a day of papers in the gallery, and from that, a book of essays was published.

Looking at the scale of what was involved, it was also agreed that the event would not happen until 1984, thereby missing the actual date of the 10th anniversary of Auden’s death by a few months. But what emerged as the process of organizing the event went ahead was the massive global goodwill there was towards Auden and the way in which a veritable cornucopia of the world’s most important literary and artistic institutions was willing to weigh in behind an unknown but enthusiastic young scholar from Trinity College Dublin in the most trusting and helpful manner. The catalogue’s acknowledgements accompanying the event are a “Who’s Who” of that world.

As always with such events, the cast of personalities which emerged lent itself to some great anecdotal lore; as the event got underway, Vienna played host to many of them. Stephen Spender arrived from London along with Auden’s biographer Humphrey Carpenter. They were billeted at The Bristol Hotel—then a rather grand but elegantly chipped and faded establishment. By this time, Spender was Poet Laureate and sported a knighthood, under which moniker he was registered at the hotel. It caused hilarious moments at the reception desk where he was always addressed as “Sir Spender,” making him sound like something altogether different to any passing English speaker. Chaperoning him around Vienna was a delightful task. He knew the city quite well from living there in the 1930s. 1984 was the time of the coal miners’ strike in England; news of its progress was his abiding obsession. In those pre-internet days, we did our best to keep him updated.

Raymond Adlam of the British Council in Vienna—a man of immense charm and erudition, a much-travelled Council officer and straight from the pages of an Olivia Manning novel—did much to keep the ever-increasing group of distinguished guests entertained. We organized a dinner for Spender in Auden’s favorite Vienna restaurant, the Ilona Stüberl, an unpretentious Hungarian bistro on Bräunerstrasse in the inner city, which Auden liked because it had something of pre-1956 Budapest about it. The young artist Mary P. O’Connor who was chosen to illustrate elements of the exhibition was among the guests. She then worked with Eduardo Paolozzi. Her massive and highly charged images of Auden’s face—“that wedding cake left out in the rain”—had been commissioned for the exhibition, and Spender very much admired them. The poet had never seen a Swatch watch and was fascinated by the one the artist was wearing, especially because it had a rotating image of Mickey Mouse.

What emerged from the Vienna exhibition and the international coverage it received was, above all, a sense that Auden’s legend lived on in Austria.

Another guest was Paul O’Grady, a brilliant Irish-American scholar whose work on Catholics in the reign of Henry VIII also interested Spender. Snatches of the conversation floated up the table, with O’Grady delivering this sentence supporting some point about Auden’s Christianity: “I think Auden would agree that a melange of incoherent prejudices is very far removed from a firm Catholic theology, anti-papal or otherwise.” One could see how such a man could get him around to talking about his relationship with Auden. Spender’s extraordinary revelation emerged: “Auden loved me, but he never really liked me.” That provided much fuel for post-dinner speculation as the guests, including Caroline Delval, whose organizational and acute literary skills did much to make the exhibition successful, wandered off into the Vienna night. Later in a nearby bar Paul O’Grady and I gave full vent to our musings on what England’s Poet Laureate could possibly have meant. We came to the same conclusion, that Auden indeed loved him, but what he didn’t like about him was his abandoning his early flirtation with homosexuality or the fact that Auden had intended Spender to be the novelist of the “Auden generation,” but he had disregarded that advice and went on with poetry.

By a happy coincidence, Auden’s old friend Leonard Bernstein was in Vienna conducting the Philharmonic, and when he heard about the exhibition, he asked for a guided tour. He ambled over from the Musikverein one afternoon with his assistant Aaron Stern. He spent an hour going through the exhibits in great detail and offered many piercing insights. When he came to a photograph of Auden and Chester Kallman, he stopped and said, “This photo tells you all you need to know about that relationship; there is Auden looking at Chester, and Chester is looking at the camera.”

I sat him down to view a BBC documentary on Auden in which the closing sequence is footage of Auden’s funeral. The Kirchstetten Village Brass Band is playing some sombre dirge, but the director chose to play as the soundtrack under the footage, a full orchestral version of Siegfried’s Funeral March. Auden had requested that this be played at his funeral, and Chester had played it on the gramophone in the Kirchstetten house. Auden said he wanted “Siegfried’s Funeral March and not a dry eye in the house.” He got his request. But now looking away from the television screen in the Künstlerhaus, Bernstein looked up and said: “Wow, not bad for a local village band!” He recalled then that one of his own early orchestral works, “The Age of Anxiety,” was inspired by Auden’s poem of the same name. He recited memoriter, “September 1, 1939,” while puffing with great dramatic effect on an untipped cigarette. He also recalled Auden’s love of opera and the poet’s many librettos composed with Chester Kallman.

Soon after the Vienna exhibition, I travelled to Athens to meet Alan Ansen, who first met Auden in New York when he attended his Shakespeare lectures and briefly became Auden’s unpaid amanuensis in 1948–49. Ansen was educated at Harvard, where he took a first in classics. He had led a somewhat bohemian but scholarly life, enabled by an inheritance from an elderly aunt. He resolved never to take paid employment during his lifetime—a resolution he fulfilled with consummate skill and not a little judicious financial husbandry.

I knew that Auden held his intellect in high esteem and highly regarded his poetry. He acknowledges Ansen’s help with “The Age of Anxiety” and The Portable Greek Reader. Ansen was a sort of muse figure to the Beat Generation and is the model for Rollo Greb in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and for AJ in William Burrough’s Naked Lunch. Indeed he is credited with having typed the manuscript of Naked Lunch in Tangier.

He was in his sixties when I met him, and during the time I spent with him, I could still see traces of how Kerouac described Rollo Greb:

He had more books than I’ve ever seen in all my life—two libraries, two rooms loaded from floor to ceiling around all four walls and such books as the Apocryphal Something-or-Other in ten volumes. He played Verdi operas and pantomimed them in his pyjamas with a great rip down the back. He didn’t give a damn about anything. He is a great scholar who goes reeling down the New York waterfront with original seventeenth-century musical manuscripts under his arm, shouting. He crawls like a big spider through the streets. His excitement blew out of his eyes in stabs of fiendish light. He rolled his neck in spastic ecstasy. He could hardly get a word out he was so excited with life.

The library came with him from Long Island to Venice and Athens. He pointed out a chair that Chester Kallman gave him, which came from Auden’s house in Kirchstetten. “What should be done with this after I die” he asked me, more as a rhetorical question than one needing testamentary advice, for he was soon on to other subjects.

Over glasses of Cinzano Rosso, he told me of Chester’s last days in Athens with a touching, genuine sadness in his face and voice. Tales of his drinking Ouzo from early morning, tales of his being robbed by Athenian rough trade, tales of insufferable loneliness drowned in a vat of drink. Ansen said he had “lost his criterion when Wystan died.” He then recited some lines Chester had written about Auden’s death:

Wystan is gone; a gift of fertile years

And now of emptiness: I found him dead

Turning icy blue on a hotel bed.

…

I shared his work and life as best I could

For both of us, often impatiently.

So it was; let it be.

He was pleased with the catalogue of the Vienna exhibition I brought for him and glad, he said, that Auden’s adopted homeland remembered and honored him.

What emerged from the Vienna exhibition and the international coverage it received was, above all, a sense that Auden’s legend lived on in Austria. Yet, there was also this all-pervasive sense that Austria had claimed him as one of her own and a feeling that he would have been greatly pleased to be so claimed by the people he lived and died amongst. Some visitors to the exhibition mentioned that the Austrian tax office presented him with a tax demand so substantial that the shock of it shortened his life. Though the bill was eventually halved, it did cause Auden—a natural worrier about money—terrible distress. His letter to the tax office is a masterpiece explaining the poet’s art, as are the lines from his poem “At the Grave of Henry James.”

Master of nuance and scruple,

Pray for me and for all writers living or dead;

Because there are many whose works

Are in better taste than their lives;

Because there is no end

To the vanity of our calling: make intercession

For the treason of all clerks.

_____________________________

The Poet & the Baroness by Michael O’Sullivan is available in paperback from Central European University Press.

Michael O’Sullivan

Michael O’Sullivan’s last work was Patrick Leigh Fermor: Noble Encounters, in which he revisits the trajectory of one section of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s famous pedestrian excursion from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople meeting many of the old Hungarian families Leigh Fermor stayed with during his famous 1934 visit to Hungary and Transylvania. He is the author of bestselling biographies of Mary Robinson, Ireland’s first woman president and later UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. He has also written biographies of the founding father of the modern Irish state, Seán Lemass and of the playwright Brendan Behan.