How Vincent van Gogh’s Favorite Works of French Literature Influenced His Art and Identity

Steven Naifeh on the Painter's Lifelong Relationship to Books

Featured image: “Portrait of Vincent van Gogh” by John Peter Russell.

Vincent van Gogh loved writers as much as he loved painters.

It was partly by immersing himself in literature that Van Gogh developed the singular, elegant voice that makes his letters such an important literary achievement. This immersion also helped give him an ability to describe so persuasively his appreciation for the work of other artists and his intentions for his own art, making it unusually possible—perhaps uniquely so—for us to see art through the eyes of an artist of his stature.

The trajectory for Van Gogh’s love of reading—as for so much else in his life—was set in earliest childhood. Every evening at his parents’ parsonage in the small village of Zundert, situated in the south of the Netherlands, ended the same way: with a book. Far from being a solitary, solipsistic exercise, reading aloud bound the family together and set them apart from the sea of rural illiteracy that surrounded them. His parents read to each other and to their children; the older children read to the younger; and, later in life, the children read to their parents. Reading aloud was used to console the sick and distract the worried, as well as to educate and entertain. Whether in the shade of the garden awning or by the light of an oil lamp, reading was (and would always remain) the comforting voice of family unity. Long after the children had dispersed, they continued to exchange books and book recommendations as if no book was truly read until all had read it.

While the Bible was always considered “the best book,” the parsonage bookcases bowed with edifying classics: German Romantics like Friedrich Schiller; Shakespeare (in Dutch translation); and even a few French works by authors like Molière and Alexandre Dumas. Excluded were books considered excessive or disturbing, like Goethe’s Faust, as well as more modern works, especially by such French writers as Honoré de Balzac and, later, Émile Zola, which Van Gogh’s mother, Anna, dismissed as “products of great minds but impure souls.”

Equally unacceptable in the household were the novels of Victor Hugo. Through the better part of a century of bourgeois consumerism and contentment, Hugo had kept the torch of idealism—the flame of the Revolution—alight and aloft. He had battled backsliding governments and resurgent religion, outraging everyone from Louis Napoleon to the Van Gogh family with his celebrations of godlessness and criminality. “Hugo is on the side of criminals,” Vincent’s mother once declared in horror. “What would become of the world if bad things were considered to be good? For the love of God, that can’t be right.”

Early on, Van Gogh’s taste for French literature, especially the most revolutionary novels, became a prime battleground in the intensifying conflict between father and son. When Vincent sent his parents a copy of Hugo’s The Last Day of a Condemned Man, it struck exactly the blow he must have intended. In an astounding about-face clearly pitched to elicit maximum outrage, he eventually even repudiated the special authority of the Bible. “I too read the Bible occasionally,” he said, “just as I sometimes read Michelet or Balzac or Eliot.”

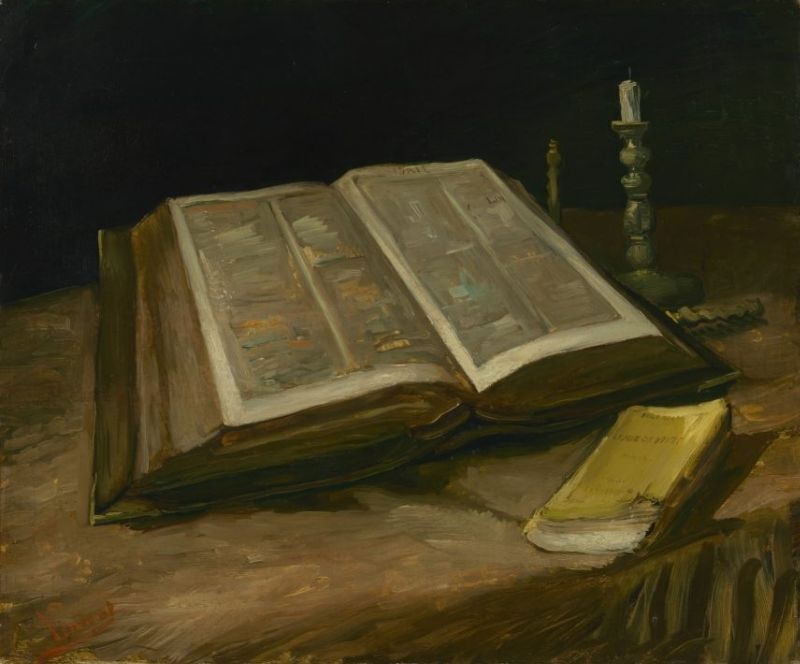

It was a battle that didn’t end with the death of Dorus van Gogh in 1885—from a heart attack that Vincent’s sister Anna blamed on her difficult older brother. When his father died, Vincent decided to dedicate a painting to him, and to include in it a group of memento mori, or reminders of death. Looking around his studio he naturally selected, first, a huge Bible that had belonged to his father. Because the church kept the pulpit Bible and his widow kept the family Bible, this magnificent tome, with copper-reinforced corners and double brass clasps, was the only Bible passed down when Dorus van Gogh died. Clearing an open place in the clutter of his studio, Vincent spread a cloth over a table, set the Bible on it, and unhooked the clasps. He pulled his easel up so close that the open book almost filled his perspective frame.

Still Life with Bible, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Still Life with Bible, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

At some point, he decided to enliven the composition with another object. Sifting through his piles of books, he selected one of the bright yellow paperback Charpentier editions of the French novels he loved and placed it on the edge of the table, at the foot of the giant Bible, a French novel serving as a final provocation even in a time of grief. He designated the book as Zola’s La joie de vivre and with provocative care lettered in its title, author, and place of publication—Paris. In a few strokes, he captured its dog-eared cover and well-worn pages—a challenge to his father’s flawless, formal Bible.

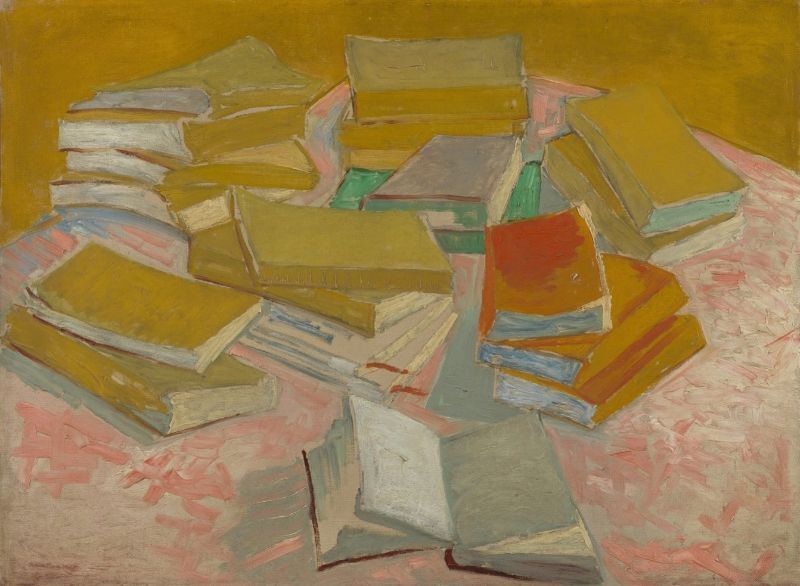

Reading remained Van Gogh’s mainstay throughout a lonely life. With few real companions, he filled the hours when he wasn’t painting with reading. He read manically, in four languages—Dutch, German, French, and English—often reading the same book over and over. He would read a single book by an author—Balzac, for example—then move on to the entire oeuvre. In time, he would undertake to reread the complete works of favored authors, “that great and powerful” Balzac prime among them.

Although Van Gogh had a special love for Hugo, Balzac, Dumas, and Zola, he read with enormous pleasure all of the great French novelists of his day: the Daudet brothers, Alphonse and Ernest; the Goncourt brothers, Edmond and Jules; the travel writer Pierre Loti; and especially Guy de Maupassant, the author of one of his favorite novels, Bel-Ami. Van Gogh would come to think that certain countries produced the greatest artists in specific art forms: the Greeks in sculpture, the Germans in music, and the French in literature.

But the French writer who had the most impact on Van Gogh was Zola. “This Émile Zola is a glorious artist,” he wrote to Theo in July 1882 as he devoured one novel after another. “Read as much of [him] as you can.” One of his many favorites was Le ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris), Zola’s celebration of the triumph of bohemian humanity over bourgeois orthodoxy. Always eager to identify with individual characters in the books he read, Van Gogh imagined himself not as Claude Lantier, the book’s anguished artist, but as Madame François, a kindly woman who rescues the book’s forlorn hero, Florent. This was an image of salvation that reverberated past differences of class and gender to the core of Van Gogh’s relationship with the prostitute Sien Hoornik—as both rescuer and rescued. “What do you think of Mme François, who lifted poor Florent into her cart and took him home when he was lying unconscious in the middle of the road?” he asked Theo pointedly. “I think Mme François is truly humane; and I have done, and will do, for Sien what I think someone like Mme François would have done for Florent.”

Reading remained Van Gogh’s mainstay throughout a lonely life.

Van Gogh was also enamored of Victor Hugo, for his forceful narrative, his soaring rhetoric, and his grand vision. And with Hugo, as with Zola, he fastened on story lines and themes that reminded him of his own life and helped him come to terms with it. On March 30, 1883, Van Gogh passed his 30th birthday alone, rereading Hugo’s tale of hounded exile, Les misérables. “Sometimes I cannot believe that I am only 30 years old,” he wrote. “I feel so much older when I think that most people who know me consider me a failure, and how it really might be so.” When he turned to Notre Dame de Paris, Van Gogh cast himself as Quasimodo, Hugo’s despised, bandy-legged hunchback. From the depths of self-loathing, he rallied himself with the hunchback’s pitiful cry: “Noble lame, vil fourreau / Dans mon âme je suis beau” (A noble blade, a vile sheath / Within my soul I am beautiful).

Piles of French Novels, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Piles of French Novels, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

But if Van Gogh saw personal inspiration and consolation in the novels he read, he saw artistic inspiration in them as well. During his confinement in the asylum at Saint-Rémy, imagining a painting of a starry night, he dreamt upon the starry nights in the books of Zola, Daudet, Loti, and especially Maupassant that he kept at his bedside. “I love the night with a passion,” Maupassant wrote in Bel-Ami. “I love it as one loves one’s country or one’s mistress, with a deep, instinctive, invincible love… And the stars! The stars up there, the unknown stars thrown randomly into the immensity where they outline those bizarre figures, which make one dream so much, which make one muse so deeply.”

Zola, in Une page d’amour, described the sky of a summer night as “powdered with the glittering dust of almost invisible stars… Behind these thousands of stars, thousands more were appearing, and so it went on ceaselessly in the infinite depths of the sky. It was a continuous blossoming, a showering of sparks from fanned embers, innumerable worlds glowing with the calm fire of gems. The Milky Way was whitening already, flinging wide its tiny suns, so countless and so distant that they seem like a sash of light thrown over the roundness of the firmament.”

Through a seamless, spontaneous interweaving of personal preoccupations and artistic calculations, private demons and creative passions, favorite paintings and favorite novels, Van Gogh was achieving an entirely new kind of art. His letters are filled with the uncertainty of a man who finds himself either on the edge of a new world or at the end of a long limb. He could not invoke Zola often enough to make the doubts go away. “Zola creates, but does not hold up a mirror to things, he creates wonderfully, but creates, poetizes,” Vincent wrote to Theo in 1885. “That is why it is so beautiful.”

__________________________________

Excerpt from VAN GOGH AND THE ARTISTS HE LOVED by Steven Naifeh, copyright © 2021 by Steven Naifeh. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint of Random House Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Steven Naifeh

Steven Naifeh is a graduate of Harvard Law School. Mr. Naifeh, who has written for art periodicals and has lectured at numerous museums including the National Gallery of Art, studied art history at Princeton and did his graduate work at the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University. He has written many books on art and other subjects, including four New York Times bestsellers.