Mother’s Day was never a real holiday to my mother—more about marketing than raising me. No white carnations or special dinners for her. But that my memoir about her, Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son, was published just before this Mother’s Day would make her smile. Likewise, that I have written about her at all.

I did not set out to write about Irma. The working title of my new book was Trouble in Mind, and it was going to be about how it was for me as a little boy and how what I learned breaking rules as a kid defined me as an adult. After several clunky drafts, I saw that the stories and details that had stayed with me over my years were hackneyed—retreaded like old tires with too many miles. In other words, I sounded like everybody else, with the same old media stories.

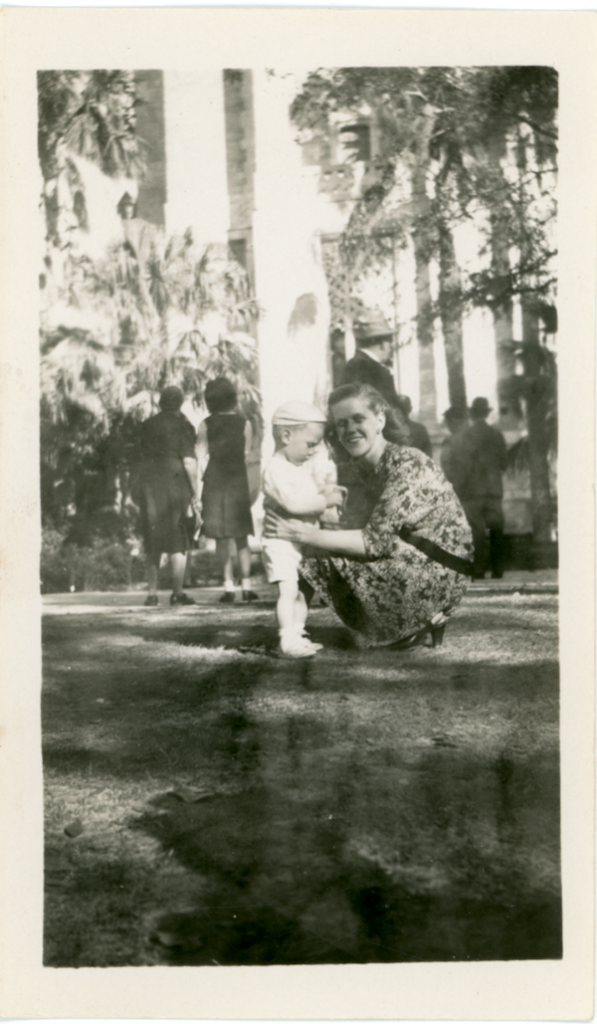

It was discouraging until I saw that the most compelling person on my pages was not me, but Irma. That simple long-time-coming but immediately obvious observation allowed me to start over, not like Irma starting over as the 25-year-old widow of a navy pilot with a 4-month-old son, but in my own way to reckon with how our lives had played out. I thought about how, when I was bored, she would tell me to use my imagination. She had been serious. But I wasn’t making anything up, rather taking generalized memory, like driving across the country when I was 5, and then letting my mind run until I suddenly saw Irma smiling, with a bright scarf around her neck, talking a highway patrolman out of a speeding ticket.

Almost immediately the annoying writer’s compulsion to talk endlessly about his or herself started slipping away until I was no longer a student of my own history, rather a son finding his way to fifty thousand words about the most important person in his life. I looked for ways my ideas about Irma might make it to the page, the sacred page where I learned to think as I had learned to read, with wonder, the way Irma had taught me.

Thinking is just selective memory anyway. Put two things together that have never been together before, and the world is changed: chaos theory. Memory works that way too. No story is told just once, but it is never exactly the same story. That was all I needed to know, except certain memories seemed to be searching me out. I knew the brain handles positive and negative information differently, in different hemispheres; troubling info, what most people don’t want to think about, takes more time to process, which means more thinking, and bad events are harder to forget and wear off more slowly, some never. But you can bury them. I was aware. Piece of cake.

No story is told just once, but it is never exactly the same story.

That was when I let go. The past would always be there, but to remember everything—madness. Better to sort the scraps of memory—snapshots, really, of the long strangeness of Irma’s life opening slowly like a good film until details came back to me in flashes. I think everyone has similar moments, when remembering something their mother did or said illuminates her. Maybe nothing is precise and none of the little pieces fit together but you can’t help seeing more if you think a little harder. In a very strange way, you can see yourself too—from a distance that surprises you. In my case the way Irma would drive with her elbow out the window when it was hot.

My memory built on itself with small truths. Irma had always said it was admirable to want to learn what she called the “whole wide world,” but you should try to know some small truths too. Remembering that I thought of a barefoot and pregnant girl I had seen in Mexico. Almost a child, really. She was sweeping a dirt yard next to a gas station in Chihuahua, where many of the migrant children Irma taught to read were from.

Associations like that can be bridges over great gaps of time. I think Irma wanted me to grow up to be the kind of serious man who knew something about the world and could stand up and tell people what he thought without showing off. The kind of a man who stood up for people, especially women. The kind of man that liked women. I knew from the beginning that men liked Irma, although I had only vague ideas what that meant at the time, or what it ever meant to her. Her attitude seemed to be that men and women were just different and that was not good or bad. They did not have to understand each other to get along—and that was sexy.

When I was in junior high school, Irma told me if I liked girls, they would like me back. It was a two-way street according to Irma, and manners were part of that, but those manners were supposed to make me feel good about myself, too. I think now that was how Irma passed me a version of her evolving feminism which allowed me to embrace strong women who reminded me of her in ways I did not quite recognize.

Soon enough, I was drawn to women others found difficult. They were more interesting simply by not going along, sometimes busting me for not paying attention or showing off. Like Irma, in a way, but, of course, not. I became was aware that women not letting me off the hook for this or that might be good for me, might be helping me evolve, in the argot of the day.

That was her alchemy, and somehow it had given me confidence that I could live in a real world.

Irma seldom talked about her boyfriends except sometimes after they were gone, when a name would come up and she would roll her eyes that she did not know what she had been thinking. What I saw, though, was that she liked them all, although she certainly did not need them. Everyone said Irma was the prettiest mom, but I remembered one time back in Duluth when I was very young, and Irma was talking on the phone.

We were dressed up to go out and I was standing next to her, waiting in my little bow tie, and Irma was telling her girlfriend, Sis, that it was never good to be too pretty. Where did that memory come from? The thing was, though, I had always known there was something wrong, even if it was complicated by details I had somehow missed only to remember now.

I imagined my unconscious dragging out such details like lost gloves that needed to be paired or thrown away. If I was going to write about Irma, I needed to shake all the trees and look closely at whatever fell out. Shake the trees? Old gloves? I winced at the tropes. I would write simply about Irma, not a mission statement, something humble to be read in a single sitting about how, before I could remember anything else, I remembered Irma teaching him the names of things, the trees and birds and insects of the Santa Clara Valley. That was her alchemy, and somehow it had given me confidence that I could live in a real world.

After I had started working at what Irma never called my career, we had a new dynamic, a kind of code. Nothing was ever wrong in our lives. No complaints from either of us. When we talked on the phone about people we had known in Burbank or Campbell there was no judgment. I was aware of this as a turn in our relationship, a way to create a better past in the face of regret. But it was on me because regret was never Irma’s style. She was teaching by example. I didn’t have to criticize anyone.

I am not sure what Irma would make of Irma. She would not have objected, but that does not mean she would not have had her own thoughts, which she would probably keep to herself. Maybe she would remember asking me what I was writing besides journalism. Like what? I had wondered. “Like the writers you like,” Irma said. Impossible, I thought, but was grateful. She was encouraging me. Irma would never judge.

_______________________

Terry McDonell’s Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son was recently published by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins.

Terry McDonell

Terry McDonell has published widely as a journalist, top-edited a number of magazines, and was elected to the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 2012. He is the author of The Accidental Life: A Editor's Notes on Writing and Writers and Irma: The Education of a Mother’s Son. He is president emeritus of the Paris Review Foundation and co-founder of Literary Hub. TerryMcDonell.com