How to Write a Novel While Driving on the Sam Houston Tollway

Andy Anderegg on Writing a Book About Escaping When You’re Going in Circles

My first car was a used convertible, its ten-year-old soft top already pulling away from the frame, already not a good idea for rain. Where we lived, there was a driving curfew, the time of night matching the years of age, just another way to tell a kid they’re still a kid.

I wanted: a set of keys I could hold in my hand (not the code to the garage door) and a cell phone. I wanted to go as far as I could. I wanted to go anywhere. I had seen the commercials. The people in cars went wherever they wanted. I also wanted a job and a credit card. I wanted a college scholarship, somewhere out of state. I wanted what I had heard called a “full ride.”

I’ve always wanted to leave home. I never once thought of staying. I wanted to be a writer, too, but listened when my dad from the front seat said I should do something that made money. I did need money, it’s true, if I was ever planning on getting the fuck out. Looking back, I had been pointing my car in different directions towards and away from things with the question in me, always there: How do I get out of this?

I drove once to a hotel. The vacancy light glowing, the gravel lit red. We asked to check in, but they said we had to be twenty-five. We weren’t. In the car, we tried to make a new plan. The rain on the roof made a loud phwap, the rain on the driver’s seat soaked into my jeans. And then: the pounding tap of fingers on my window, the motel proprietor completely backlit yelling at us, muffled through the rain, “You can’t stay here. You need to leave.” We had been wanting to leave, we wished he knew. We didn’t want to stay there either. We hadn’t turned twenty-five yet.

Broken up, I drove as far as I could west. I had a big cold drink in the cup holder and I felt like I was running after the sun, hoping to give myself a little longer in the light, the car a time capsule I could wrap myself in, pick myself up later, sift through the old, outdated things with wonder and not with such sadness.

I drove to get a job, a job as a waitress, applying at each one along the strip mall by I-35, near the good Walmart. At the second restaurant, my car wouldn’t start, so I went back in and asked for a glass of water. And so it was that I worked for years at the first restaurant, an IHOP in front of a Home Depot, the only place my car had taken me.

I drove after curfew and through a red light and naive as I was back then, when the police car did its light show behind me, I stuck my head out the window and asked for directions. He let me go, no warnings, pointing the way to the on-ramp.

When I quit waitressing, I did it by ducking beneath the pass so the manager couldn’t see me on the camera feed. He hadn’t put me on the schedule, so I wanted to leave. He said if I didn’t want to be there I could leave and never come back. Had he thought I’d always wanted to be there? Maybe he didn’t mean it, but if someone wants me gone, I want me gone too. I drove across the parking lot to the bookstore and walked around like I was in an alternate universe. Wasn’t I trapped in that blue-striped apron? Wasn’t I still wearing non-skid black shoes? I bought a book with the syrup sticky cash from my apron pocket.

Looking back, I had been pointing my car in different directions towards and away from things with the question in me, always there: How do I get out of this?

Once, I drove three hours to Texas just because a friend hadn’t been yet. We drove down and back before my Spanish class at 12:30. Where did we go, but to another place, all on our own, the gas station, snacks galore.

And at night, wondering if we were ever going to make it in the world, I drove with my friends to drive-thrus, us ordering for each other or leaning over and ordering for ourselves, passing food out as it came from the window to the window, always a decision of where to drive to eat. A hill is a good spot.

But once, I had to drive to the Venezuelan consulate in Houston with my boyfriend to do some paperwork. We drove all day because could we afford a hotel? No, we could not afford a hotel. So we drove and the entire time I wondered why there were not more Venezuelan consulates in the United States, but I wondered it not in the way I might wonder now. I wondered it more like, why did they put it so far away from me?

We got there, our handwritten directions our only guide—our spiral bound map only outlining the roads in the state we lived in—and the consulate was on lunch break. They would be for another hour and a half, a person behind glass told us. The sign said something else, and I pointed at the sign and read it and started to say how it didn’t make sense, and also the person we were talking to wasn’t on lunch was she? And my boyfriend told me to accept it, sign or no sign, that the sign meant nothing, and they must all be on lunch.

So we went on lunch, too, but where we really went was onto the Sam Houston Tollway, where you don’t just pay to get on or off, but you pay, as they say, as you go. That is, you pay and you pay and you never stop paying, the toll booths popping up like nightmares. I thought I’d lose my entire life’s fortune (not much, but all I had) tossing coins into the baskets on that tollway.

*

When we got off the tollway, the surface streets offered me a repeating series of strip malls. I do not mean this to deride Houston, but to deride the entire system we’re alive inside of. We were lost because the world did not seem new, one street to the next, did not seem to offer something we had not seen before.

It is a myth that the way we can get out is by car, a myth in the way most myths myth, in that it is also true. We can get out by car.

Back at the consulate, we had to get the unaffordable hotel room and come again the next day to do the same thing but with fortitude and not despair. We slept and tried again, and we got the paperwork sorted, which it turned out, was not necessary unless you were talking about the way my boyfriend’s father thought it was necessary to move money using my boyfriend’s identity from US dollars to Venezuelan bolívars on the not-black market, except aren’t they all?

Next to the Sam Houston Tollway is another human invention, something uncommon: a continuous, toll-free frontage road for its full length. On that consulate visit, I didn’t know it was there so I didn’t know how to get on it, only knew how to hold on and hope I could get out one day, could get to a place where I could claim the promises.

I learned it later, that we exist inside an imagination. Every human creation, everything that we’ve made, could be re-made differently. You could build a home for yourself and be safe. The roads out there could be free. We can have any good part of life we want.

_________________________________

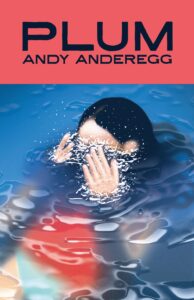

Plum by Andy Anderegg is available via Hub City Press.

Andy Anderegg

Andy Anderegg was born in Austin, Texas and lives in Los Angeles, California. She holds a BA from the University of Oklahoma and an MFA from the University of Kansas. Her fiction has been shortlisted for the Dzanc Books' Prize for Fiction and named a finalist for The Clay Reynolds Novella Prize from Texas Review Press.