How to Win The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest

Eight-Time Winner Lawrence Wood Offers Some Tips For Constructing the Perfect Phase

Choose Your Words Carefully

“The difference between the almost right word and the right word,” said Mark Twain, “is the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.” That’s especially true in the contest, but does the right word have to be funny? Neil Simon thought so. In his 1972 play, The Sunshine Boys, an aging vaudeville comic gives his nephew a lesson in comedy by insisting that words with a hard “k” sound are funny.

“Chicken is funny. Pickle is funny. Cab is funny. Cockroach is funny.”

The writers of 30 Rock mocked that advice repeatedly, first by having the inept Dr. Spaceman (pronounced spa-CHE-min) explain that he can’t stop giggling while discussing an organ transplant because of the hard “k” sound in kidney. In another episode, Liz complains to her producer Pete that “Jenna accused me of trying to destroy her because her lines don’t have any ‘k’ sounds, which she thinks is the funniest sound.” Pete then checks his texts and says, “Oh, my God. My cousin Carl crashed his car, and now he’s in a coma at the Kendall Clinic.” Meanwhile, Jenna narrowly escapes a falling stage light during a rehearsal of a Macbeth sketch and exclaims, “I could have been killed! It’s the curse,” causing an intern to laugh and then apologize by saying, “Sorry. Hard ‘k’ sounds.”

I don’t find words inherently funny. In the context of a particular caption, however, some are definitely funnier than others. Before providing an example, I have to explain something about this Leo Cullum cartoon:

When it appeared in The New Yorker as part of the caption contest, the drape was a dark shade of red. Until that point the contest had never featured a color cartoon, and they were a rare sight in the magazine. In fact, the issue with Cullum’s drawing included a feature called “What’s So Funny About Red?,” which was what Harold Ross reportedly said when asked why The New Yorker didn’t publish cartoons in color.

While looking at Cullum’s cartoon, try to imagine the red. It’s essential to understanding my winning caption, which is based on the popular misconception that bulls are enraged by that color: “You should be happy. How many husbands even notice window treatments?” I doubt I would have won had I ended on the word “drapes” or “curtains” (even with its hard “k” sound). The joke would have been the same, but “window treatments” made it funnier.

Here’s another example from David Sipress, who once sent The New Yorker a cartoon of a Mayan soccer game: “There’s a severed head laying on the ground, and another guy’s holding up a regular soccer ball, and the Mayan in charge of the game is saying, ‘I don’t care if it’s bouncier—it threatens the integrity of the game.’” Only after Sipress changed “bouncier” to “more bouncy” did The New Yorker buy it.

Sometimes you can get away with a word that is technically incorrect. Here is my winning entry for the contest featuring this drawing by Mick Stevens:

“That explains the signature on the floorboard.”

Lawrence Wood, Chicago, Ill.

My friend Kevin, who’s an architect, congratulated me by writing, “That’s not a floorboard. It’s a baseboard.”

Eliminate Unnecessary Words

While we’re on the subject of words, don’t use too many. They can ruin a potentially strong caption. “The real challenge in a contest like this,” says Mankoff, “is making [a] general funny idea work in the shortest possible form—using the economy of language and emphasis that’s necessary for a good cartoon.” Here’s the winning caption from a contest that featured this drawing by Frank Cotham:

“Don’t worry, you’ll be running in no time.”

Tony Bittner, Pittsburgh, Pa.

That came in third out of nearly five thousand entries in crowdsourcing. An almost identical entry—“Don’t worry, you’ ll be up and running in no time”—came in 1,221st. How could two little words (“up and”) account for such a discrepancy? There are two reasons. First, the crowdsourcing algorithm can lead to wildly different rankings for nearly identical entries. Once a voter sees a really well-worded caption, they will likely dismiss as “Not Funny” every similar caption that’s less well-constructed. The slightly inferior caption then starts appearing less frequently, which means it gets fewer votes overall, and this cycle repeats itself until the caption ends up with a final ranking that’s deceptively low. Second, thinking of a good joke isn’t enough when other people will likely have the same thought. You must carefully craft the joke and deliver it as well as possible by, among other things, getting rid of every inessential word.

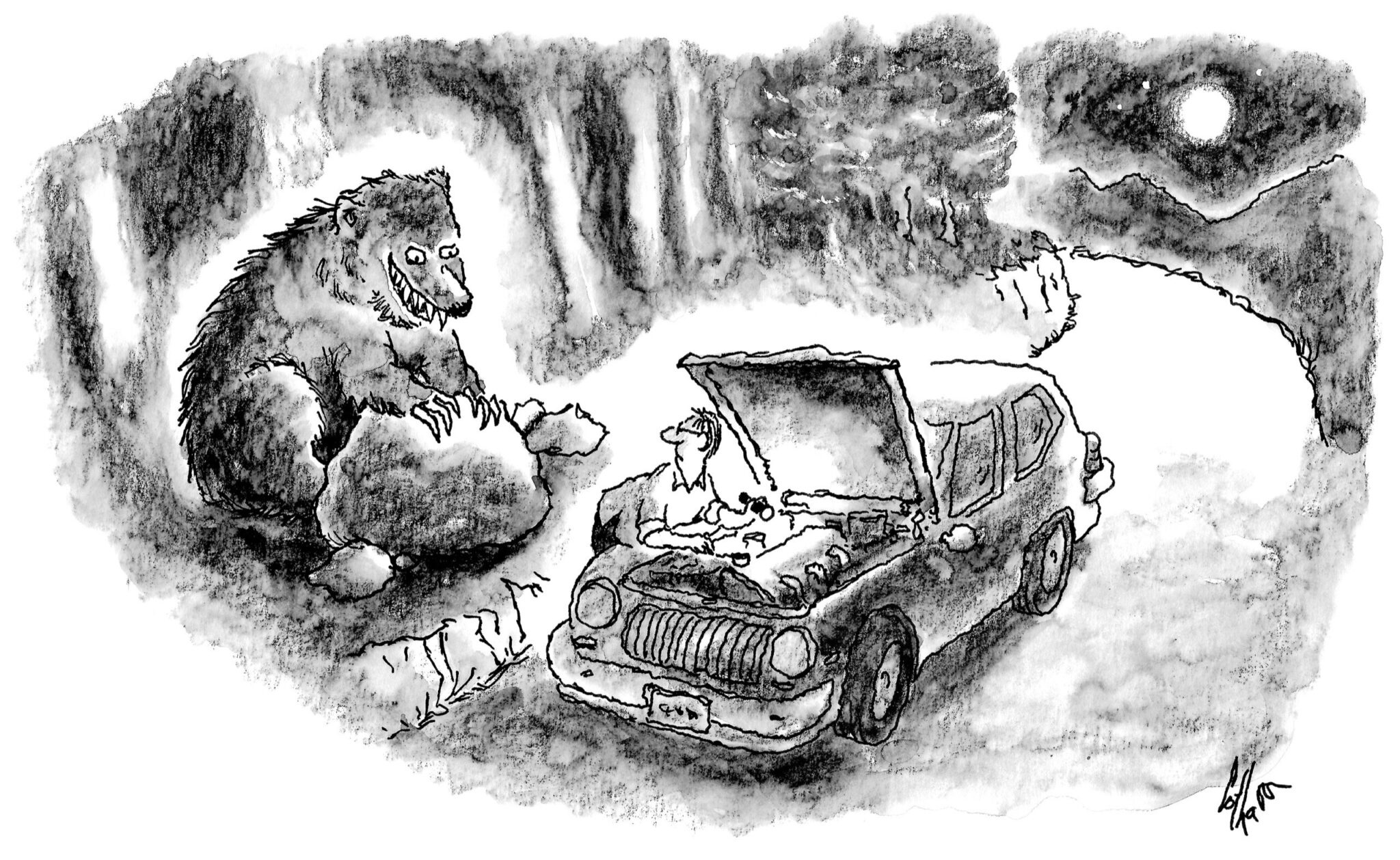

That’s how Harry Effron won the contest featuring this drawing by Drew Dernavich:

“The hours here are obscene.”

Harry Effron, Briarcliff Manor, N.Y.

Effron subsequently confessed that he could not claim full credit for his entry:

The caption started as my dad’s idea, which he submitted. It was, “The hours here are obscene. Yesterday, I didn’t get out until %$*#@.” Looking back at past contest winners, I realized that the caption was too long. The joke in the first half was enough, so I submitted just that.

Though he stabbed his father in the back, Effron’s victory demonstrates the importance of being succinct.

Not every great caption, of course, is short:

That caption had to be long because the cartoonist, Alex Gregory, was establishing a pattern before ending with something unexpected, and every word was necessary to build the rhythm of the joke before getting to the punch line. Gregory was following the “rule of three” (which he expanded to the rule of four), a comic principle he alluded to in this cartoon:

__________________________________

Excerpted from Your Caption Has Been Selected: More Than Anyone Could Possibly Want to Know About The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest by Lawrence Wood. Copyright © 2024 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Lawrence Wood

Lawrence Wood has been a finalist in The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest a record-setting fifteen times and won eight contests. For more than twenty years he was a lecturer in law at the University of Chicago Law School, where he taught a class on housing and poverty law that Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia dismissed as a “waste of time.” Lawrence is currently the supervising attorney at Legal Action Chicago.