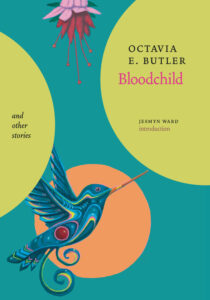

How to Survive in Broken Worlds: Jesmyn Ward on Octavia Butler’s Empathy and Optimism

“When I discovered Butler’s work, I discovered myself.”

I can’t remember when I first read Octavia Butler’s work. It wasn’t in high school. I never encountered her in my coursework, as my required reading looked nothing like the books I found in my personal reading: I read The Last of the Mohicans, Catch-22, and The Catcher in the Rye and little there resonated with the world I knew.

I had grown up in a poor/working-class family in rural Mississippi, where I spent years eating government cheese, red beans, and rice, and drinking powdered milk. I lived in my grandmother’s four-bedroom house with fourteen other relatives and watched my extended family bear the brunt of poverty and racism through my childhood and adolescence.

I spent those years wandering through my school library stacks, finding books by Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Ntozake Shange, Richard Wright, Gabriel García Márquez, and Margaret Atwood. I found sustenance in literary writers and in science fiction and fantasy writers, too, needing the escapism of that kind of storytelling, which I had been drawn to since I was a small child and first read Tamora Pierce and Robin McKinley—but the only science fiction and fantasy I could find in my school library were by Frank Herbert, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Isaac Asimov.

I didn’t encounter Octavia Butler’s fiction in university, either. I majored in English, and I sought creative writing classes and literature classes that specialized in the African Diaspora. I read African writers and Black British writers and Black American writers and Black Caribbean writers, but all the work I read was poetry and literary fiction. It was good to study these artists, to seriously consider the kind of work I had been starving for in high school, but even though I attended school in mid- to late 1990s, when Octavia Butler was a living writer, full in her artistic flowering, I never found her work in the bookstore stacks or on the syllabi of my courses.

Even though I attended school in mid- to late 1990s, when Octavia Butler was a living writer, full in her artistic flowering, I never found her work in the bookstore stacks or on the syllabi of my courses.I never really encountered any sci-fi or speculative fiction: when students submitted science fiction short stories or fantasy in creative writing workshops, my peers shunned them. They said the work was amateur, not serious, wasn’t about real people and therefore, real issues. I sat quietly at my desk, swallowing their critiques whole, quietly ashamed of the pleasure I got from reading sci-fi and fantasy.

I must have read Octavia Butler’s work for the first time in the early 2000s, when I was living in New York City as a young twenty-something, working as a publishing assistant. I had more money, not much, but more than I’d had in college and high school, so I’d take the train to The Strand, where the stacks stretched on and on. My browsing blossomed; I needed that.

I was floundering through life. Tragedy had loosed me from my moorings, my understanding of what the world was and how it worked, and it sent me spinning: a drunk river killed my brother Joshua in October 2000, and his killer was never held accountable for his death. I’d voted in my first presidential election and watched in confused horror as Bush was appointed by Supreme Court ruling.

I’d watched smoke billow from the Twin Towers on 9/11 and then spent hours walking from midtown to Brooklyn, peppered in ash. I’d marched through Manhattan to protest Bush’s preemptive war with Iraq, foolishly thinking our collective uprising would have some kine of impact, bitterly disappointed when I discovered it did not. I’d visited home and jumped from my car’s window and swum through the floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina, and then lived in shock in the desolation of the aftermath.

Her character development was disturbingly true to what I knew of the world, of poverty, of desperate human beings.I found Parable of the Sower by chance in The Strand’s stacks. I devoured it. Butler’s prose was forthright and rhythmic. Her imagery was stark and startling. Her character development was disturbingly true to what I knew of the world, of poverty, of desperate human beings. It was harrowing and dark, and it seemed to reflect some ineffable terrible truth I found mirrored in the world. It reminded me that worse presents were possible. I sought out more of her books and found Parable of the Talents, the Lilith’s Brood trilogy, and Bloodchild and Other Stories. In Bloodchild, Butler says this about readers: “Actually, I feel that what people bring to my work is at least as important to them as what I put into it.”

In my twenties, I found this to be true, sunk in grief, bewildered at the savagery and terror of the 2000s; when I discovered Butler’s work, I discovered myself. I saw myself in her characters, empathized with them as they struggled to live in untenable worlds: in untenable circumstances. I knew they knew the taste of ash, the black scramble of floodwater.

I’m in my mid-forties now. If life revolves in cycles, I find myself in another crucible, another terrible span of time. The COVID-19 pandemic lingers and evolves, leaving weakened immune systems and millions of bodies in its wake. The Supreme Court struck down Roe, and the politicians in power can’t seem to grasp the urgency of the moment, to understand that not only are childbearing people uniquely disenfranchised by this ruling, but that we will die without access to abortion health care.

My partner of thirteen years died at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, leaving me with two grieving children and the charge of living in a fractured, unthinkable present. His death tasks me with this: every day I must wake and live. I must choose to move and breathe and speak and believe that there can be good in this world, in humanity, even though this fresh grief invites a drift toward despair, even though, as the ill characters do in “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” I have wanted to claw out my own heart in hopelessness.

I saw myself in her characters, empathized with them as they struggled to live in untenable worlds: in untenable circumstances.In multiple allusions in the preface and afterwords in Bloodchild, Butler alludes to the despair and bewilderment she encounters in her own life, and how she wrestles with it in her work. “Amnesty” is about an interpreter, kidnapped and tortured by aliens as a child, who works for and with that same alien race as an adult to improve communication between humans and their visitors. In the afterword to “Amnesty,” Butler writes that the story was inspired by “the things that happened to Doctor Wen Ho Lee of Los Alamos—back in the 1990s when I could still be shocked that a person could have his profession and his freedom taken away and his reputation damaged all without proof he’d actually done anything wrong.”

“Speech Sounds” follows a pandemic survivor who has witnessed the devolution of humanity after a fast-spreading disease robs those left of speech or the ability to read and write. In the afterword to “Speech Sounds,” Butler writes: “’Speech Sounds’ was conceived in weariness, depression, and sorrow. I began the story feeling little hope or liking for the human species, but by the time I reached the end of it, my hope had come back. It always seems to do that.” She elaborates on this in the afterword to “Bloodchild,” the title story, with:

When I have to deal with something that disturbs me … I write about it. I sort out my problems by writing about them. In a high school classroom on November 22, 1963, I remember grabbing a notebook and beginning to write my response to news of John Kennedy’s assassination. Whether I write journal pages, an essay, a short story, or weave my problems into a novel, I find the writing helps me get through the trouble and get on with my life.

This is how Butler finds her way in a world that perpetually demoralizes, confounds, and browbeats: she writes her way to hope. This is how she confronts darkness and persists in the face of her own despair.

This is the real gift of her work, a gift that shines in Bloodchild: in inviting her readers to engage with darker realities, to immerse themselves in worlds more disturbing and complex than our own, she asks readers to acknowledge the costs of our collective inaction, our collective bowing to depravity, to tribalism, to easy ignorance and violence. Her primary characters refuse all of that. Her primary characters refuse to deny the better aspects of their humanity. They insist on embracing tenderness and empathy, and in doing so, they invite readers to realize that we might do so as well. Butler makes hope possible.

The hope might be tenuous, and our lives might not be what we envisioned in these ruptured realities, but new ways of being are near. These are futures where we might turn from despair and build another family after a pandemic. Where we might elect to foster life and connection. Where we might wake every day and choose to breathe, to walk, to do work and heal ourselves and others even though we struggle with suicidal ideation, with nihilism, with grief. Bloodchild is a template for how to survive, how to thrive, in broken worlds, and Butler’s work is ever prescient, ever powerful. Her voice: a rough balm.

_______________________________

From Jesmyn Ward’s introduction to Octavia Butler’s Bloodchild, available from Seven Stories Press