How to Fictionalize the World's Greatest World Record Holder

In Which a Man Is Willingly Kicked 43 Times in the Groin

Bibhuti Nayak, my dear friend and, in fictionalized form, subject of my second novel Man on Fire, has been breaking world records for almost 20 years. His first successful attempt came back in 1998, when he allowed four of his karate students to kick him in the unprotected groin, 43 times in a minute-and-a-half. A slew of records followed over the next two decades, under the banner both of Guinness and of Limca, its less famous and more accommodating Indian cousin. In between assignments as a respected journalist for the Times of India, Bibhuti has channeled his physical prowess and mental fortitude into a series of challenges that most men would shrink from. Thus he holds the world record for most concrete slabs broken over the groin with a sledgehammer (three); highest number of one-handed cartwheels in one minute (34); and highest number of sit-ups in one hour (1,448). In the course of setting this last record he gave himself a brain hemorrhage and spent three days in a coma; he had neglected to place any padding underneath him and hit the back of his head against the concrete floor 1,448 times.

Bibhuti has trained himself to overcome pain. Through years of martial arts training, meditation and a strict vegetarian diet he has found a way to turn pain off, like switching off a light. In a country where poverty, disease and social inequality are rife, I can understand his desire to insulate himself from the ravages of fate by building a body as impervious as any temple. Perhaps, at the age of 50, he is also attempting to insulate himself against mortality. But his endeavors are not for personal glory alone. When I ask Bibhuti why he has chosen to concentrate his record-breaking activities in the category of “extreme sports” he tells me this: “I do it to show the common man that there is happiness on the other side of pain.”

I have known Bibhuti since 2009, when I first saw him on TV demonstrating one of his records for a documentary series about Indian oddballs. In all that time, I had read and written and talked about his records, but I had never witnessed one being broken live and in the flesh. In October of 2015 I got the chance to change all that. I had been invited to Mumbai to appear at Tata Literature Live, an annual literary festival that draws writers from all over the world. On the face of it I would be there to talk about Man on Fire, which had been published in India a couple of months before. But Bibhuti came up with another, more compelling reason why I should visit: he wanted to break a record for me. I was afraid. So far, over 18 years and 14 world record attempts, he had a 100 percent success rate; what if my presence was an unlucky omen for him? What if his first failure came on my watch? I wouldn’t be able to forgive myself.

He told me not to worry. He wanted to give me a special gift in return for writing the book for him. I consented. Had I not done so I risked offending him greatly. And besides, how often do you get to see a world record broken in your honor? It would be the closest I’d ever come to having a song written about me. It was irresistible.

Literary festivals generally comprise a series of talks about books. An opportunity for author and reader to meet and converse, a chance to sell books and spend time with other writers in the relaxed but often corporate-sponsored settings of the green room or the hotel bar. As far as I’m aware, and I’ve been to quite a few, they are not commonly chosen as the venue for a Guinness World Record attempt, so we were breaking new ground in more ways than one.

The record Bibhuti had selected seemed, to him, a straightforward proposition. He aimed to achieve the highest number of knuckle push-ups in one minute. The official Guinness record stood at 79, only set by American Ron Cooper a few months before, in June 2015. Having given himself no time to practice (he only knew I was coming to India five weeks in advance), and not fully recovered from the three most recent records he had set—all on the same day, also in June—he picked an activity whose technique he was familiar with and which required no specialist training. On his first practice attempt he managed 80. Not a lot of room for error. Yet he assured me the record was in the bag.

I wasn’t so confident. Have you tried knuckle push-ups? They’re hard. I got down on my hands and knees at Bibhuti’s home, the day after I arrived in Mumbai, and tested myself. I got to six before deciding, quite reasonably, that knuckle push-ups are not for me. In my defense, I was jetlagged and the marble floor was unforgiving. But still, I was left in no doubt of the magnitude of the task Bibhuti had set himself. I even suggested he might want to sit this one out. I would understand. There would be no shame in admitting it had come too soon for him.

Not a chance in hell. He was committed. Besides, the festival had made its preparations and advertised the event. The Guinness adjudicator had been requisitioned and friends and colleagues had been forewarned that another slice of Mumbai history was about to be made. There was no backing out.

And so I found myself on stage, taking part in a panel discussion about biographies with three eminent and perfectly amenable fellow authors, while internally cursing myself to high heaven that I had allowed my friend to risk public humiliation on my account. I prayed that he wouldn’t injure himself. I fretted over the image of him spread-eagled on the same stage I now sat on, drained and defeated with the catcalls of a disgruntled crowd ringing in his ears.

Bibhuti was in the audience with his wife and son and a handful of his loyal supporters. He looked so relaxed. He smiled at me and waved. I wanted to bolt for the door but I had my obligations.

When the discussion ended we authors accepted our applause graciously. There was some milling around afterward while photos were taken and business cards exchanged. The stage was cleared and made ready for the next event: Bibhuti’s record attempt. The audience was encouraged to stay in their seats if they wanted to witness their local hero’s latest triumph. Like the man himself, they seemed entirely comfortable that he would succeed, almost to the point of insouciance. Perhaps as Indians they had seen and experienced so many bizarre and dangerous things in their daily lives that the prospect of a man defying gravity and time by doing a push-up on his knuckles once every 0.7 seconds held no particular fascination to them.

My wife and I were the only ones in the room aware of the stakes. If Bibhuti failed, I would be the callow Brit who dismantled a god on Indian soil.

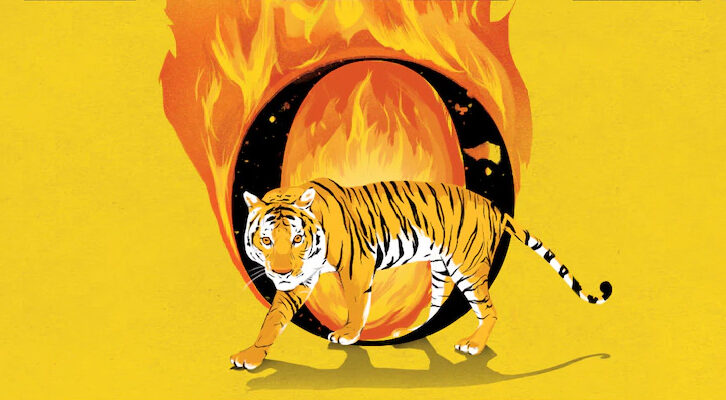

I wished Bibhuti good luck as he took the stage, my voice cracking with the anxiety of it all. While his supporters busied themselves in checking their stopwatches, Bibhuti removed his socks and sat down cross-legged, facing the auditorium. He closed his eyes and began to meditate. He had told me how, once a trance-like state of calm had been attained, he could deflect pain and all thoughts of defeat as surely as if he were a tiger shrugging off the advances of a fly. I had believed him, because he had seemed so plausibly sure of himself. Now my belief in him was to be tested for the first time, I could barely contain my fear. My heart began to pound, my mouth went dry. Had I taken for granted my friend’s singularity, used it cynically to prop up my own sense of uniqueness? In presenting him to the world through the pages of my fiction as a man invincible had I only fueled a myth that would inevitably, and catastrophically, crumble when faced with one examination too many? What had I created, and what responsibility must I accept for the death of that creation, here in a Mumbai suburb that had welcomed me as an honored guest? I clung to the hand of my wife beside me and waited for it to be over.

For fully ten minutes Bibhuti was still and silent. His hands strayed to the thighs of his jeans, wiped them for comfort. A small, inscrutable smile played at the corners of his mouth, as if he were being told a secret. Sometimes he would open his eyes, very briefly, as if to check that he was still present in the world as he had left it. I couldn’t begin to fathom what was passing through his mind. He was communing with something unknowable. At last he roused himself, and it was as though he were waking from a deep and restorative sleep. He slowly breathed out, turned to the announcer to indicate with a diffident smile that he was ready.

A hush fell.

Bibhuti assumed the kneeling position, placed his fists on the floor, arms straight, then extended his legs so that he was balancing on the tips of his toes. Already defying gravity. His two timekeepers consulted their stopwatches, waited for the their hands to sweep around to 12 o’clock. At the required moment they called start in unison, and Bibhuti began.

He pumped out one pristine push-up after another, his forehead brushing the floor on each downward stroke, arms bent into a perfect v then straightening with military precision on the upward, his back kept parallel to the ground at all times. His breath could be heard in the room, steady and strong, hypnotic. Immediately I lost track of time. There was no visible clock to which I could refer, no way of following his journey toward his goal except to count each repetition in my head; but so dulled were my senses by the fear of an imminent collapse that I lost the ability to keep score. Bibhuti was on his own up there, and I had gone to a place where I could not help him.

Bibhuti had told me how time would alter when he was in the midst of an attempt. How it would slow down and become a bird that he could hold in the palm of his hand. In these moments of heightened endeavor all external forces would loose their grip on him, and he would be free. How I wished now for this freedom. Instead I felt as if I were being crushed by the forces of time and fate. Each moment that passed that I could not measure heaped a further weight on top of me. All I could do was watch my friend toil in a solitude he had chosen for himself. He looked so lonely up there, and I wanted to call out to him with a message of solidarity, but I couldn’t risk upsetting his rhythm.

And then he began to falter.

His repetitions slowed and became ragged in their execution, and he started to breathe heavily, gulping for air. I thought it was all over. Tears came, scalding and acidic. I glanced to my wife; she was unperturbed. A voice behind us cried out, “Come on sir, come on!” I joined in. I was frantic now, shaking. I sang for my friend in the throng of strangers. Bibhuti cried out too, a desperate animal, his strength draining from him. I had never seen him vulnerable like this and it cut through me like a knife. I felt like I was watching him dying. It was all my fault. He strained and buckled and somehow stayed up, produced a few final repetitions before the announcer called time and he let himself drop to the floor.

Applause roared out. People around me rose from their seats and congratulated each other. I didn’t know what was going on.

“How many?” I asked my wife. “How many?” Tears were rolling down my cheeks and I felt both ridiculous and sanctified by the investment my heart had made in this man of valor and strange habits.

Onstage the counts were compared and verified and within moments an official verdict came. “Ladies and gentlemen,” the announcer called, “we have a new Guinness World Record. Eighty-three knuckle push-ups in one minute, congratulations to Bibhuti Nayak!”

Bibhuti was lifted onto the shoulders of his supporters. I sobbed and hollered and took leave of my body. I clambered onto the stage to be with him. Once he was lowered we found each other and shared a long embrace. He saw my tears and gave a gentle laugh. We posed for photographs, arms around each other, drinking in the moment for the gathered press. Bibhuti accepted his felicitation timidly, and as soon as the photographers had their shots he took me aside and led me out to the corridor to escape his well-wishers.

“I did it for you,” he said.

“Thank you,” I replied. There was nothing else to say. The flow of adrenaline was slowing and a feeling of intense peace washed over me. Or was it just relief?

Later, my wife and I took Bibhuti and his family to dinner at my hotel, the iconic Taj Mahal Palace. We chose the same restaurant where he had bought me dinner the first time I had visited Mumbai to meet him, back in 2010. His wife was radiant with quiet pride, his son stood taller beside a father who had nothing to prove to the world. Bibhuti was quiet throughout, reflecting on his latest achievement. Achievements that have not brought him fame or fortune. Risks that have taken their toll on his body, for rewards that might seem modest to most. His name in a book and on a certificate he can hang from his wall. A reputation for self-discipline that does not extend beyond the few people he chooses to call his friend. But I am one of those people, and his story has become mine in the telling.

I did my fair share of reflecting that night, too. On fate and accidents and the chance encounters that bring people together, yes; but also on the discipline it takes to keep us bonded. When I first set out to write Man on Fire, it was with the intention of bringing Bibhuti’s story to a wider audience. Now, a year after the book was finished, my obligation to Bibhuti has become bigger and more precious than merely getting his spirit down on paper: it is to remain his friend despite the oceans that separate us. It is a promise I look forward to fulfilling, just as he looks ahead to his next, improbable feat of endurance.

Stephen Kelman

Stephen Kelman is the author of the novels Pigeon English and Man on Fire. Pigeon English was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and is also a set exam text on the UK high school curriculum. He is currently working on his third novel.