How to Draw a Novel

Tracing the shapes of the stories we tell

Mexican writer Martin Solares likes to draw the shapes of novels—describe the plot, in a literal sense. The following is the introductory chapter to How to Draw a Novel, a work-in-progress translation—in collaboration with poet Tanya Huntington—of his original Spanish title, Cómo Dibujar Una Novela, which will feature entirely new chapters.

Some say novels are constellations composed of words; others, the closest we will ever come to a powerful incantation. From page one, they transport us to a world where every word conceals more than one intention and the very laws of physics operate differently. Baptized by their authors with suggestive, enigmatic names that sometimes constitute the first words of the spell being cast, novels are frequently baptized a second time by their readers, transforming them into something more endearing and familiar.

While we are compelled to choose a single bough from the tree of life, albeit a dazzling one, a well-constructed novel can lay claim to several branches at once: the most unexpected and passionate, the most unsettling and amusing. Then there are those that recount the greatest failures, the most ambitious exertions, or the feats that once seemed impossible to us.

Novels do not openly tell us how to live, but they do tell us stories. In difficult times, when one seeks to overcome life’s cares, the novel offers us a tale that seems to have been written expressly for the present time.

Full of surprises, novels have also become increasingly beholden to beauty. They know something of life, and if they happen to be acceptably structured, they even seem to think for themselves. Only instead of making arguments and presenting us with a thesis, antithesis and synthesis, novels offer us scenarios, conflicts and characters. Thanks to them, we are able intuit something about the way in which this world is configured.

This book, certain that novels do indeed think for themselves, has chosen to comment on some of their more fascinating traits: what are the strategies used by writers to design the opening lines of their stories, how do their characters take shape, at what speed does the story progress, how do objects that find themselves inert in everyday life behave within the world of fiction, and what images are created by novelists to describe their novels, as well as a pair of very brief texts regarding how these stories tend to end. One of the chapters in the book asks us whether it is possible, upon reading certain novels, to have the sensation of conceptualizing or even inhabiting a building made of words, one that begs to be visited and assiduously enjoyed, as if it were a delightful dream.

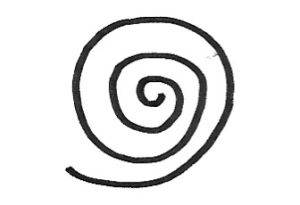

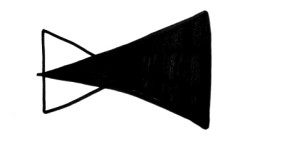

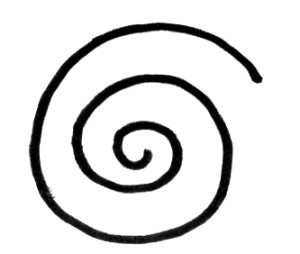

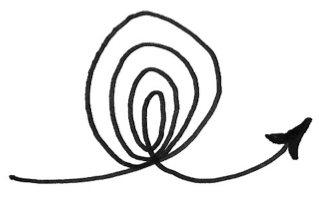

Anyone who has attempted to draw the shape of a dream will agree with me as to how difficult it is to grasp the stuff they are made of. Seen from above, these drawings tend to resemble a spiral or a whirlpool, the outer limits lost in the distance:

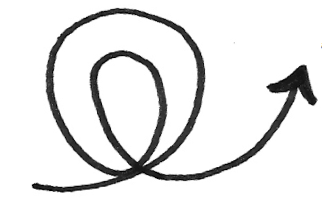

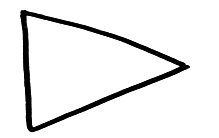

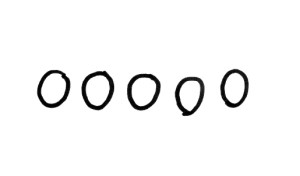

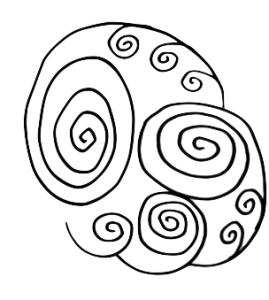

This is a shape that recalls the design of a short story, whereas the drawing of a novel is inclined to be less constrained, more roomy:

The short story is composed of vertical prose that tends to round out, while the novel’s horizontal prose takes flight every time we ask ourselves: what happens next?

The short story, not unlike a dream, lifts off, gives us a few surprises, then comes to an end. The novel, on the other hand, is a voyage that, like a dream once we awaken, can never be forgotten.

· · · ·

No one ever asks whether or not novels think for themselves but nonetheless, they watch over us and draw their own conclusions. Accustomed to being slippery sorts, they adopt different forms and techniques in such a way that makes it hard to track or define them. Up front, we must accept that they possess not a single form, but many; that they use a variety of means to tell their stories, and that realism is but one of these.

According to Thomas Pavel in his monumental La Pensée du roman, not only do novels think, they have their own philosophical system similar to idealism—if idealism, instead of making arguments through thesis, antithesis, synthesis, were to present us with characters, settings, and plots; if instead of reasoning with us, it were to tell us stories whose veracity is impossible to prove.

The novel is where certain ideas are best confronted and, moreover, one of few such spaces that possess an indisputable geometry. Après Pavel, one would have to complete a taxonomy of the many different forms taken by the novel. Whoever took it upon himself to do so would discover that despite their amazing diversity, novels have a great deal of interest in our stimulation. While a good short story submerges us only once in wonderment, the novel captures our attention with constant doses of surprise, courtesy of the forms its stories adopt and the idiosyncratic way it moves forward.

Let us not forget what Blanchot wrote in The Space of Literature regarding that fleeting something that explains the origin of all writing: “A book, even a fragmentary one, has a center which attracts it. This center is not fixed, but is displaced by the pressure of the book and circumstances of its composition. Yet it is also a fixed center which, if it is genuine, displaces itself, while remaining the same and becoming always more central, more hidden, more uncertain and more imperious. He who writes the book writes it out of desire for this center and out of ignorance. The feeling of having touched it can very well be only the illusion of having reached it…”

To show that it is possible to represent the shape of a novel, we hereby propose a system that will allow us to do so, in the best of cases, with just a few strokes of the pen:

I.

Read any novel, and read it with one question in mind: what is its shape? What attire, what figure does it assume while addressing the reader?

II.

Everyday language expresses ideas clearly; the novel says things differently. Instead of ideas, the novel offers ideas embodied in characters or styles; instead of reasoning (thesis, antithesis, synthesis), the novel offers us a group of characters who will confront one another.

III.

While the reading of a non-literary text advances in a linear fashion, phrase by phrase, the reading of a novel creates various simultaneous pathways that do not necessarily advance at the same pace or in the same direction. The novel branches out or is braided, it advances by leaps or by bounds, it runs or stops short, it goes back to the start or takes one small step now and again until reaching the end of the story.

IV.

Once we have finished reading it, we become aware of the fact that each phrase has contributed to creating a shape that does not reveal itself fully until the very end. Sometimes our awareness of the creation of this shape is such that we feel impelled to draw.

V.

In order to draw a novel, one must portray the appearances and disappearances of the main narrator, the ways in which different points of view alternate, the relationship that exists between the central and secondary plotlines and, above all, the artifice: the way the author has decided to position his material by postponing certain elements, by foreshadowing or concealing parts of the information.

Take for example a boring novel. One where nothing ever happens, either in the writing or in the story itself. If we were to draw a straight line from left to right on the page, this would reflect the trajectory of the hero, and we would have a failed narrative lacking any tension whatsoever:

On the other hand, if we were to place (as is frequently the case with adventure novels) various obstacles in the path of the main character, so that he finds himself obliged to get around them, as is the case in The Odyssey, or in certain stories from A Thousand and One Nights, the novel would gather interest and a certain rhythm, and would be more happily read. It will have taken on the shape of a roller coaster:

One must take care that these challenges or walls confronted by the protagonist are of a diverse nature, so that each one of them can put different aspects of his character to the test. Yet at the same time, each and every one of his adventures condemns him to continue wandering the seas, unable to return to his fatherland. For tireless Odysseus, it is not the same to blind the Cyclops as to convince Circe or Nausicaa to let him go. Similar anecdotes try different aspects of his being: his capacity to move the king of the Phaecians to pity, his use of imagination to find an escape route from the cave, his talent for conquering beautiful women. Each turn of the roller coaster is completely different, and yet we might say that they all draw the same figure:

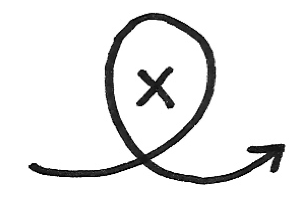

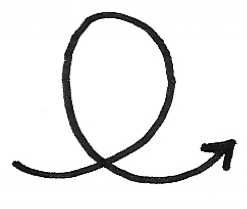

Upon completing each of these adventures, we go back to the main situation: Ulysses continues to be lost at sea, trying to find his way back home. If we examine each one of these unexpected events closely, we will find that despite their differences, they inevitably form the following drawing:

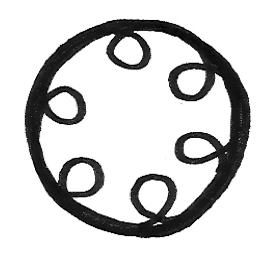

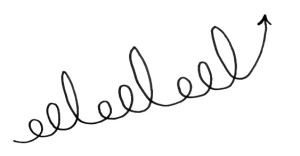

That is to say, a digression. This is the most characteristic movement of a novel. It is found in predecessors like A Thousand and One Nights and it is also in Don Quixote, it is in The Wild Palms by Faulkner and it is in The Trial by Kafka. If the novel were an animal and were allowed to roam free, it would roam in digressions:

Now then: while all novels trace digressions, not all of them share the same scope or strategy. For example, rather than complete full turns that close sooner rather than later, some choose to open up a series of parentheses:

What novels of this ilk, such as Life Is Elsewhere by Milan Kundera, do is to detain the linear narration and delve into aspects that are increasingly profound as the life of a character emerges bit by bit, like ripples expanding on the surface of a lake.

The moment comes when we reach the center and these parentheses start to close. Perhaps if we were to take a closer look, we would note that each parenthesis also contributes poetic detail regarding the character or theme: the profile of the character depends on the strength of these features. And it goes without saying that all novels are parentheses: the result of a test, a stage of transition in the lives of their characters.

The following could very well be the drawing of a mise en abysme, any case where a secondary plot takes place within the main story, the novel within a novel:

To close, I would like to include a few examples. At first, everything points toward Pedro Páramo taking shape as follows:

But it will not take long for us to discover that the protagonist dies in these initial pages, whereas the dead tyrant, invoked from the opening phrase (or from the title, even) gradually gains greater weight and vitality until he has taken over the novel completely:

Now let’s take a look at The Autumn of the Patriarch:

As you may recall, every chapter of this novel begins with an obsessive vision of the same image, that of buzzards entering the presidential palace. Bit by bit, from there unfold the tales of the patriarch, each of which acts as an almost independent story that winds up leading us back to the original image.

No matter what order they have chosen, the many readers of Cortázar’s Hopscotch tend to draw a form like this one when challenged to do so, as I myself have been able to corroborate:

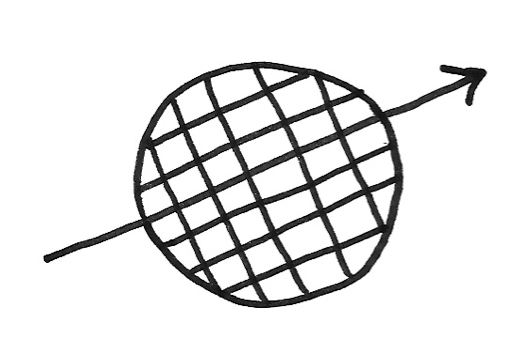

While on the other hand, The Savage Detectives by Bolaño would seem to suggest this shape:

The rising diagonal corresponds to the diary of the poet García Madero, interrupted by the testimonials of dozens of characters evoked by Lima and Belano, although their paths may have crossed only once. At first glance, the central chapter recalls a strobe lamp like those found in discotheques of the 1970s, which is when the action in this book takes place.

It is not too much of a stretch to point out that, as if the originality of this shape were not enough, Bolaño tended to develop fantastical forms, each of which is in a class of its own. This, in addition to the calibrated delirium Amulet, By Night in Chile or Monsieur Pain have to offer us—deliria that have their variants, as any reader can confirm…

Bolaño launches Nazi Literature in the Americas as if we were dealing with a set of independent stories, joined by a single theme:

But suddenly the final text, which is actually a novella in its own right, introduces us to the author of the stories and the book, which had already begun to resemble an encyclopedia, is suddenly transformed into a novel—a dress rehearsal for The Savage Detectives, perhaps.

Another Bolañesque shape worthy of note is doubtless that of 2666, where the five parts that compose the novel can be read independently but share settings, themes and characters that intersect to a greater or lesser degree. This book opens with “The Part About the Critics” and “The Part About Amalfitano,” which have little to do with the murders of women that take place in Santa Teresa but, on the other hand, are of slightly greater interest than “The Part About Fate” and are the main subject of “The Part About the Crimes.” Finally, “The Part About Archimboldi” shows us a full-body view of the mysterious author who obsessed critics and has returned to Santa Teresa in search of the murderer of women:

Some of the novels written by César Aira perform a similar twist. They branch off from the main theme little by little until forming a single, powerful digression. Far from losing the reader’s attention as it loses steam, this digression injects enthusiasm into the main theme in such a way that it is reinforced and gathers even greater impetus. Aira is a true artist of digression or, as he refers to it, of fleeing forward:

At this point, I suggest that we recall novels are not two-dimensional objects. If we were to take an X-ray of any of the aforementioned books, we would see that they are animated by interest, by threads of agitation. As Umberto Eco once said, novels are also agony-generating machines.

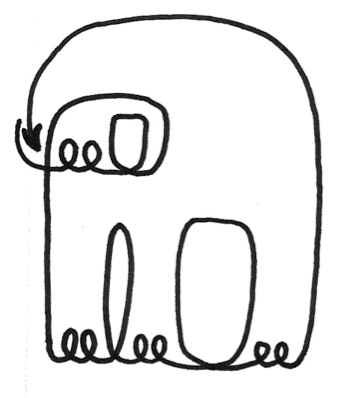

If the behavior of a novel were to be filmed in slow motion, it would become clear that each novel has a particular mode of displacement. Despite its elephantine volume, Don Quixote, for example, executes constant digressions, some of which are interspersed as novellas:

A counterpoint novel by Vargas Llosa, let’s say Who Killed Palomino Molero?, alternately told in the voices of two characters, one of whom contemplates the investigation he is carrying out while the other divulges a series of key memories, would advance in a coherent, yet peculiar fashion:

The Feast of the Goat would add yet another twist to the previous shape, given that it alternates between three points of view:

And while we’re on the topic of great complexity, two novels by Fernando del Paso have a lot to say on the subject. As the author himself has confessed, José Trigo is shaped like an ascending pyramid that climbs up to a central chapter, then starts to descend once more:

News from the Empire, on the other hand, delivers a monologue by Carlotta followed by three chapters that, for the most part, act as perfect short stories. This particular shape is repeated over and over until the novel runs out of chapters:

In my opinion, She-Devil in the Mirror, by Horacio Castellanos Moya, has one of the most original structures to be found in a crime novel. Here we have nine confessions by a female character talking to her best friend on a cell phone. As the story advances, we wonder whether the woman might not be suffering some form of hysteria and whether her girlfriend actually exists:

Artificial Respiration by Ricardo Piglia progresses differently. This is another novel composed of four great story lines, all of them vertiginous: the correspondence between Marcelo Maggi and Emilio Renzi about Enrique Ossorio, the delirium of Senator Luciano Ossorio, the vertiginous letters that seem to arrive from the future into the hands of a mysterious censor, Arocena, and the narration of a Polish man named Tardewski, featuring tales about some of the buddies he chats with at the local cafe. While everything seems to indicate that the center of the novel is the story of Uncle Marcelo Maggi, the story takes a much broader turn and ends where it began: with the inheritance of some papers under strange circumstances:

In one of his most famous essays, Jorge Luis Borges suggested that there are shapes that try to enter this world through artistic fancy. Some shapes attempt this discreetly, continuously across those thresholds we call novels, and a select few of them succeed.

Animations by Benjy Brooke.