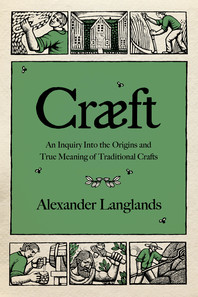

How to Dig a Hole—and Other Pieces of 1,000-Year-Old Wisdom

Alexander Laglands Looks Into the Old Way of Doing Things

While I can talk a good craft, I’m no craftsman. I’ve turned my hand to all sorts of things over the years, and at times of brimming self-confidence I like to consider myself a Renaissance man, but when I get down off my high horse the expression “Jack of all trades, master of none” is definitely more fitting. But if there is one thing I’m pretty good at, it’s digging. By this I don’t mean digging ditches—although I’ve dug a fair few in my time. When I mean digging, I mean archaeological excavation. I’ve often struggled with the idea that excavation is a craft. Sometimes I see it as a science, a series of methodological steps to deduce a series of processes—past events—from a set of physical remains. A bit like forensic science. At other times, I think it’s more about basic practical aptitude. So, in the same way that you can either put up a set of shelves or you can’t, you can either dig or you can’t. But then at other times I’m seduced by the idea that excavating requires some kind of ineffable ability. When fellow archaeologists used to say of someone else on the circuit that they could or couldn’t dig, the insinuation was clear: anyone can dig. But can you dig?

Digging has obsessed me from a very early age, and I assume this is one of the reasons why I gravitated towards archaeology. I remember marveling as a little boy at how quickly my father could dig. When I grew up, I promised myself I would be able to dig as fast as my dad. For one job, when he wanted to run a service trench down the length of the front drive, he considered hiring a mini-digger and driver. The quote, when it came in, seemed pretty reasonable. But being the tight-fisted Scotsman that he is, my dad had other ideas. Emerging from the shed a few hours later with his self-made hybrid spade—a scaffold pole hafted to a steel spade head—he set about digging the trench himself. It was how he used it that I was so intrigued by: thrusting, kicking, levering and flipping in a fluid and repetitive motion. There was clearly something of the Highlander in my father’s blood wielding his makeshift spade like a cashcrom (the traditional peat-digging spade).

I’ve also realized that in my passion for digging there probably lies a subliminal connection with the past behind us and the earth beneath us, another two of my passions in life. I don’t just mean that by digging archaeologically we can connect with the remains of past societies, but that through the act of digging itself we can experientially connect with past peoples. From prehistoric hill forts to Roman roads, fenland drainage, ditches, tunnels, dykes, cellars, causeways, canals, midden pits, foundations, irrigation systems, railway embankments, moats, road sidings and mines, it’s clear that Homo sapiens has been as much a digger as a maker. In fact, almost every period in our island’s history is characterized by some form of digging.

Since retiring from full-time archaeological excavation I’ve found solace, and a renewed passion, in a particular type of digging, and one from which I’ve learned an enormous amount about myself and our human past. It is the digging we do for food. Few people have cleared virgin ground by hand in order to grow food. I have, and as far as my lower back was concerned, four times was three times too many. Digging over a vegetable patch is hard enough but such beds have invariably already been broken, and the soil in a well-worked garden plot, if it had reasonably high levels of seed germination, will already be fairly stone free. A good grower will also have kept the levels of organic fertilizing matter high, making the soil soft, spongy and responsive to the turning spade.

Virgin ground is a different prospect. In all my years of historical farming and petrol-free gardening, I’ve found that there is one tool, the mattock, that ranks above all others when it comes to turning a wilderness into an area that can produce food. Other garden implements flatter to deceive. The spade, for all its sharp and neat lines, is redundant when even the smallest stone, cushioned by compacted subsoil, renders its slicing motion ineffectual. The fork, while successfully navigating around such stones to reach the required depth, often lacks the strength in the tines to lever the earth free. We’ve all seen the twisted, buck-toothed tines of garden forks that have been asked to do jobs for which they are little match. But drawing the mattock from the toolshed and slinging it over your shoulder as you march off in the direction of the ground you intend to break represents not only a commitment but also a recognition of the work entailed.

Few undertakings in the world of manual labor, perhaps with the exception of ditch digging and quarrying stone by hand, place man closer to the base works of humankind’s evolutionary journey. If you really want to get close to the past, as close as you can possibly get, then take a patch of unforgiving land and attempt to feed yourself from it. Doing so opens a window into the eternal struggle of human existence.

For my own part, I was foolish enough to refuse the loan of a petrol-powered rotavator, willfully blind to the time it would have saved. Time is money. Yet, this was a journey I was determined to make. Breaking ground, I felt, brought me viscerally into direct contact with the past. I wanted mud on my boots. But not because I’d traipsed out on a jolly ramble to survey the archaeological remnants of some prehistoric fields in the landscape. What I wanted was to dedicate the time and effort to recreating my own version of them.

So what is a mattock? Dating back to the Bronze Age, a mattock resembles a pickaxe but with wider blades of similar size set in opposing planes at either end of its head. On one side a vertically set blade acts as a kind of axe while the horizontal blade opposite takes more the form of an adze. Usually, it’s the horizontally set blade that sees the bulk of the work, but every now and again a disruptive root submerged beneath the path of your work requires severance. Here’s where the vertically set blade comes into its own. Mattocking the ground is a relentless process. Working in three-foot strips, you gradually plod your way up and down the plot. Each clod broken free of the ground is the result of lifting a seven-pound block of iron above your head and bringing it crashing down, shattering the earth beneath your feet.

It’s not long before your hands are on fire with blisters. The sweat stings into the creases around your eyes and a numb, menacing twinge develops in your lower back. This is a job that tames you. Having started out with all the vigor of youth, boldly hammering away at the ground, you very quickly tire. The swinging motion becomes wilder and less controlled as your muscles weaken. If you’re not careful, the mattock will drop short of your target, skid off the surface and swing dangerously close to your shins. You stop. Panting, you survey the pitiful results of your power burst. You pace around it, breathing heavily and mentally calculating how much energy you’ve expended against the small patch of ground you’ve covered. Choosing not to dwell too long on that, you then start again. Gradually your pace slows and, like a horse brought in from the plains, you are tamed into the work. You resign yourself to it. Your breathing moderates as you become methodical, more controlled. This is a marathon, not a sprint. Your breaks are regular, but short. You give yourself enough time to straighten up, stretch your back and clean the blades of the mattock with your raw hands.

I did a lot of mattocking while working as an archaeologist.

Archaeology in the field, at the actual point of excavation, has strange parallels with basic agricultural digging. In most modern scenarios a machine would be used to dig out, say, a six by six-foot-square pit. Indeed, most construction companies these days are so scared of litigation that they won’t countenance any other method for fear of accident and injury insurance claims. But if that six by six-foot-square pit just so happens to be a medieval midden pit, packed with precious archaeological data, then it can only be excavated by hand. And because of the necessary pressures placed on archaeological processes by the construction industry—for whom the archaeology is usually undertaken in the first place—it’s agreed between construction engineer and archaeological supervisor that a happy medium, somewhere between the hand trowel and the mini-digger, can be employed: the mattock.

However, swinging a mattock in the service of archaeology is rather different from using it to break ground. Because care and attention are required when excavating valuable archaeological deposits, and because you’re often working in confined spaces with other archaeologists, the business end of the mattock is rarely lifted above the head and swung wildly down. The technique becomes more one of a chipping away, of retaining enough control to pull out of the hacking motion should you expose what might be an important archaeological find. Even so, it’s just as laborious, and more so if you have to spend all day bent double. Luckily, when breaking virgin ground such caution is not required and you can use the weight of the mattock head to your advantage. My father’s mantra—always “let the tool do the work”—rings in my ears whenever I wield a mattock. Controlling the speed and direction of the swing, guiding the seven-pound iron lump down with a touch of added force is invariably enough. During this period as a jobbing archaeologist I found myself on one particularly challenging site. While we were under pressure to get the job done so that the building of a vast commercial complex could get underway, an old Irish construction worker gave me a sage piece of advice.

Seamus was part of a team putting in service and foundation trenches all around us, a measure of how pressured the situation was that this was happening before all the archaeological investigation had been completed. He’d been watching me excavate a series of vast medieval pits on the south bank of the Thames opposite the City of London. While he sat comfortably in the air-conditioned cab of his mini-digger, there I was in the baking sun hacking away with my mattock, feverishly trying to get the job done on time. Seamus was no stranger to this type of work. Over an after-work pint he told me about his youth and his immigration to England in search of employment in the late 1960s. He’d found work in the highways and construction industry, as many of his fellow Irishmen had at that time, and had learned the trade the hard way, in an age before mechanical diggers. As a consequence, he’d probably forgotten more than I’ll ever know about digging holes by hand. His advice was simple and can be extended to so many aspects of life.

“Are you right-handed, Alex?” he asked.

“Yes, Seamus.”

“Do yous want to end up like the hunchback of effing Notre Dame?”

“No, Seamus.”

“Well, for the Lord’s sake, swap the effing mattock over to your left hand every ten minutes, lad. With every blow you’re twisting your effing spine.”

I paused for a moment, considered, and duly gave his advice a try. At first it felt clumsy, and I wasn’t getting nearly as much work done. I tried to keep it up but gradually the lesson faded and I resorted to my old ways. About a year later, however, Seamus’s advice came back to haunt me. During the excavation of a vast Iron Age ditch section on a site on the outskirts of Worthing in Sussex, I twisted my upper body and spent the next three months in agonizing pain. Now I religiously swap hands at regular intervals with most tools, whether sawing wood, raking leaves or chiseling timber. I even clean the teeth on the left side of my mouth with my right hand and the teeth on the right with my left hand. All because of Seamus.

__________________________________

From Craeft, by Alexander Laglands, courtesy W.W. Norton. Copyright 2018, Alexander Laglands.

Alexander Laglands

Alexander Langlands is a British archaeologist and medieval historian. He is a regular presenter for the BBC and teaches medieval history at Swansea University. He currently resides in Swansea, Wales.