Nervous? Paul Mahon asked his wife, hoarsely. Tess stood looking out of their bedroom window, searching the river. Looks like another good one, she said, glancing over the tall trees as mackerel clouds slipped between the green tops.

Paul said: It’s to turn.

Right, she said, quietly.

You sure you’re OK?

Yes, Tess said.

Don’t overthink it, first day back and the beginning of term always makes you nervous, Tessy.

It’s just apprehension, Tess said, shivering into herself. She rubbed her hands quickly along her arms. There was a nip to the autumn air. A fat crow perched beside another on the telephone wire beneath their window. The wire stretched down under their weight.

Tess had been feeling panic for months now. Panic when she woke. Panic before sleep. She had blamed brandy for making her heart race, beer for making her groggy, Xanax for spacing her out, panic from adjusting her antidepressants. She had eaten carelessly over the summer months, a see-saw of bingeing sugar, then intermittent fasting with no routine or motivation. Mostly she blamed the injections, the up and down of it all; bursting-out-in-tears in one moment and in another, mad feelings of overwhelming elation flooding her. It was an unsettling see-sawing. I don’t care, it’s not for me, what’s for you won’t pass you, and then, mostly, who deserves a child anyway? State the world is in

until one thought dominated

who’d bring a child into this world?

It’s normal, Paul said, sitting up. He rested his head against the velour headboard. The thing with you, Tessy, is … and I’ve read about this …

Paul Mahon rarely ever missed an opportunity to tell someone a personal feature he noticed in that moment, an interpolation he backed up from a book he had read, with a title he could never remember.

Thing is, he said, you’re always like this on the first day back, worse than the students. Then, he said as he clicked his fingers, you’re grand. He folded his freckled arms. By evening you’re back in the swing of it. You work yourself up so much, Tessy—they’re just kids.

You’re right, Tess said in a thin whisper. Yes, you’re right.

And then he was silent. And this denoted agreement.

*

The last time she was at work in Christ’s College, Tess was pregnant.

Early. Eight weeks. Six days. Four hours.

Tess watched over the birds.

As long as I’ve known you, you worry. By October you’ll be floored and that’ll put paid to your anxiety. You’ll be right as rain then.

Right as rain or floored? Tess said.

Floored, Tessy, so floored you won’t have time for anxiety. He puffed up two pillows, and fixing them behind his freckled shoulders, he sat up.

A white feather came free and floated onto the floorboards where it lay quivering. The feather steadied itself. Duck or goose, she considered, which reminded her of a greasy roasted bird sat in the bowl Paul’s mother served Christmas dinner on. Every year the same faces at her dinner table. Every year the same ugly platter with large sunflowers handed down for dead fowl.

Mind the boys, she’d say, girls can mind themselves.

She would kiss Tess twice, awkwardly, like on a French film and not on the Irish west coast where people are never certain how to greet one another. Tess was set to inherit the platter. This is for you, Mrs Mahon said as she carried the heavy dish to the table, to mind my boys when I’m gone.

Her sons would clap.

The oldest son began every sentence with now this is just an opinion and monologued with such gusto you would be forgiven for taking every word as absolute fact. The younger son was a tech head and excused from general manners and often turned up stoned and obnoxious at family meals. He’s tired, Mrs Mahon would say and after dinner, the older woman, a stout woman with lashings of sweet perfume and a ruddy face, linked Tess to the kitchen where they washed and dried the dishes and where she talked incessantly about soap operas, online grocery stores, or the state of Brooke’s Hotel on the Square, how urgently it needed reupholstering.

Tess held her breath until the feather lay still.

Paul leaned out of bed, tapping his hand flat along the parquet floor until it landed on his laptop and he plonked it on his stomach. The bed sheet was pitched up by his knees.

Tess looked in her wardrobe and groaned.

Wear navy, Paul said, powering up the machine. You look good in navy.

*

In your marriage, and correct me if I’m wrong, but it’s been a couple of weeks now, and I’m sitting here listening to you both, and what I’m hearing is a problem shared really seems to be a problem doubled. Would you both agree? So we need to get past this, this needs effort on both your parts, problems need sharing, you need to be there for one another, retreating into yourself is not helping, Tess. I’m interested in your piece. Paul has articulated much these past weeks, and I would like for the next few weeks to hear from you, Tess. I understand your family environment was very different to Paul’s, I think we have all agreed to recognise that, but it is difficult for Paul to fully understand it, we need you to explain it. You are withdrawing again, Tess, and Paul, I think you need to let Tess in, you are overcrowding her, she has opinions and I think we might need to hear them. I understand, you like to fix things, offer solutions, but listening is a solution. I know you are here to save, to try to save this relationship. Am I right? Is this ultimately why you are both here? But you must find the right language for Tess. Maybe you need to, gently and I mean this with great respect, back off a little. If she is saying she is stifled, we should listen.

*

Paul disagreed with the counsellor and considered the sessions a challenge: a time to defend himself with rigorous rebuttal, and so he took to defending their marriage at every session, reiterating how good they both had it, even when time was up. Once he demanded a double session but the counsellor refused and Paul found it difficult to understand how she could not give up her lunch break for them, and even as he went down the stairs to the door of the industrial estate, he continued protesting. Even as he turned the key in the ignition of their Honda to drive from Galway to Emory, he stopped, looked at Tess and said: That woman is not well, Tessy, as he released the handbrake. We could teach her a thing or two about marriage.

That was their last session.

Tess had had a far more concerning childhood, so Paul suggested she avail of the lady-to-talk-with-on-a-one-to-one, it might be good for her.

Tess stood in front of their mirror now and lifted her shoulders up and back. She had developed a habit of hunching over. She twisted the top off a pot of cold cream, dabbed some on her cheekbones, patting it in under her eyes. As it melted into her skin, it made her eyes water.

You want coffee? Tess said, pulling on a navy sweater. Great, Paul said, tapping on his keyboard—no milk. Milk made him wheezy and occasionally it ignited a flare-up.

Tess pushed the balls of her feet into a pair of Converse without opening laces—a childhood habit—and she held the banister going downstairs, unsteady, cursing quietly.

Downstairs, light flooded the kitchen and last night’s takeout remnants were strewn across the marble island. Orange-crusted foil boxes, fried onions, yellow rice grains, chicken bones, red-wine rings on the countertop and beer cans folded over like dead birds were just heaped on a deflated plastic bag. Tess gagged as she picked dried teabags from around the sink.

*

Tess had convinced herself that she’d be pregnant again by the return of school. Even if she couldn’t visualise herself with a child. Even when the tests had had two lines, even when the tests had read PREGNANT. But this morning’s preparation and thoughts of school had blindsided her.

Alexa, play ‘Creep’ by Radiohead, Tess said, rinsing plates under the tap.

Playing ‘Creep’ by Radiohead …

Alexa Volume 8 …

I’m sorry I do not understand your command, playing ‘Creep’ by Radiohead from Spotify …

Alexa, Volume 8, Volu … Alexa … ALEXA. PLAY FUCKEN ‘CREEP’.

I’m sorry, Goodbyeeeeeee.

For fuck’s sake, Alexa, Tess said, stomping on the foot lever of the bin. She jerked out two sacks, dry recyclables and sweaty landfill. She walked into the back yard, banging the bags off the French doors. The landfill bag left a stain on the glass. Outside, green weeds sprouted through patio cracks. Paul didn’t lay weedkiller—he had conscionable objection to it and spent all summer on his hands and knees, loosening weeds with a little scraper and pulling lanky ones out of the ground, only for another to grow by morning.

Tess spent the summer in a lounger reading books and drinking beers. They had been unable to afford a holiday after the final round of IVF, which had resulted in three embryos. This retrieval was low, very low for a woman who had yet to reach her fortieth birthday, Dr Green said. After which, two were implanted. Tess miscarried, weeks of bleeding, pain and crying in bed, crying in the shower, crying running from shops when a baby would call out or a woman pushed a buggy in her way.

Paul’s sperms were flyers Dr Green said when he saw Tess back in Clinic, crying uncontrollably. Yes yes yes so painful, Green’d said again, and then, rather unremarkably, he announced it just was what it was.

They had one embryo left.

Somewhere in the hospital in a container were fragments of them both. Tess thought about it when she reached into the small freezer for a rubber ice tray, or parents said at the annual parent-teacher meeting, He’s trouble because he’s our last, a surprise, I had two already. Two is loads. Three is a handful.

One last shot.

Next round they said in the Clinic, as though she should order pints in the pub.

Tess had screamed at Paul as she was miscarrying: I’m fucking barren. Paul was horrified and went to his brother’s for a few nights to give her space.

Oh fuck you, she’d screamed as he left.

Tess liked the space, then, she even liked the word barren, though she never used it in front of the other women in the Clinic’s waiting room. There they said: It’s not happening, or, We’re having problems. Barren was an explosion, an active word that pounded out of her lips. She thought of the summer in the desert with her first boyfriend, the same summer her Granny Liz, who been there for her all her life, died while Tess was padding along in the stifling heat in another country, the same year her father, Jennings, disappeared into himself on the streets, the year she was so madly in love with Luke that she never wanted to return.

Good things can happen in dry places. Barren cacti, barren villages, fertile Vegas was one example. If anything sprouted inside her aridness, it would be cause for much celebration.

Or consideration.

But Vegas is not all winning. People come out broken.

Tess Mahon, you have an inhospitable womb, she had said loudly to herself in the Clinic. Some people had incomplete cervixes, sperm with low mobility, no tails, half tails, some had incomplete reasons and many, like Tess, defied medical science as to why the world did not want them to reproduce. As egotistical as this sounded, it was how Tess considered her infertility—the world’s conspiratorial way of proving that she and Paul were not meant to parent. She had once read an article about women who could not carry a baby for psychological reasons and when she admitted this Dr Green stopped talking to her about mental fatigue. Tess accepted fatigue as a reasonable explanation for her hostile body. And because she agreed with him, Dr Green said that Tess Mahon was a most unusual patient.

But she was not unusual. She was detached.

Take for example her mother’s death:

Tess was a toddler and too young to remember her mother, but she had no hesitation in talking about her death, if asked. Tess knew her mother was dead. She never felt the presence people speak of, only something of what it was to miss a mother on nights she watched her father wriggle across the kitchen floor ending in the corner against the stove in a ball, drunk. Tess accepted her mother was dead. Dead like dogs and goldfish and things on windowsills in arid heat, dead like orchids with sunburn crawling up their leaves.

She also accepted that it was prudent not to trust people.

*

They were almost a decade married now and to avoid misinterpretations in the way they communicated, they had grown polite and consistent with each other. To Tess, it was as though she had capitulated. She stopped giving Paul her point of view. And Paul had stopped worrying about what ailed Tess. He worked hard. She had stuff, stuff that was absent from her childhood, and in that sense, he was a good provider. In the end Tess fell silent. And not in an all-encompassing and awkward way, just in the way of gentle politeness, like how you might meet and greet the postman or a parent in school. However, lately, her body was less inclined to polite hostility. It was increasingly difficult to override the urges she still had to function, to be held, to cry, to fuck and recently, Tess craved sex without any purpose other than to orgasm and cry out.

Paul had similar feelings, though neither of them broached this with one another, and while language came readily to Tess when dealing with herself alone, having one-way conversations over all of her choices on her long walks in the woods, or on her way to school, now she no longer tabled these discussions with her husband. Together Paul and Tess Mahon had grown politely obtuse. A space, the counsellor said, was major red-flag territory. Though both of them disagreed. Sometimes it felt simply harmonious.

*

After cleaning the kitchen, Tess pulled a pan out from under the sink. She grabbed ingredients from the fridge. She cut a chunk of cold butter from its foil pack on a wooden chopping board and placed the lump into the ceramic pan. Then she cracked in four large eggs and watched the yolks wobbling. Turning up the heat, she whisked, left the eggs to cook. She lifted a silver coffee pot from the windowsill, taking apart the pieces and rinsing each, drying them carefully before she filled the pot’s belly with tap water, and scooped in spoons of coffee, tapping them down into the steel funnel, compressing the coarse powder with the back of the scoop. Tess screwed the parts together and placed it on the hob next to the eggs, and whisked. She chopped wiry chives, sprinkled them in and spooned in crème fraîche, before turning off the wheezing coffee. Finally, Tess served the eggs on two elaborate plates with gold edging and warm soda bread. She drenched hers in salt and it felt rebellious. Salt apparently interfered with her cycle: dehydration: ovulation: the plumping of ovaries: the pushing of eggs to the surface: the scraping for a small return and come mid-term: the dilating: the Petri dishes: re-insertion: last chance.

But just before eating, the memories surged in Tess, and she lost her appetite.

*

I’m off, Tess said, sponging make-up on her nose. Then she opened a box of cereal and shoved her fist inside, retrieving a free toy cat that she stuffed into her bag.

Bye, Paul, she said. Have a good day.

Paul came running and said: Oh, yeah, here … wait … here, wait up, love, and he planted a kiss on her lips. All best now, d’you hear me? Head up, Tessy. You’ll have holidays in no time. Best part of being a teacher, eh? he said, as she walked out of the front door.

Out on the footpath she turned right after the small garden gate that was left swinging in the gentle breeze.

There was a red sky in the distance.

Shepherd’s warning.

June, July and August, Paul called out after her.

__________________________________

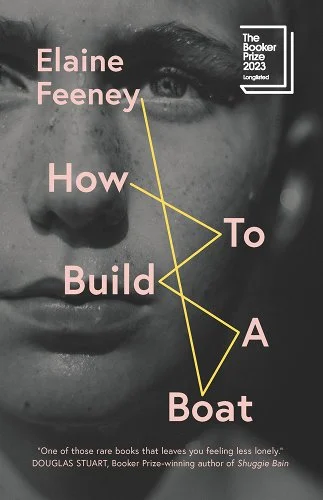

Excerpted from How to Build a Boat by Elaine Feeney. Copyright © Elaine Feeney, 2023. Excerpted with permission by Biblioasis. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.