How to Bartend

Rabih Alameddine on Life, Death, and Soccer During the Last Pandemic

1.

I was the best of bartenders, I was the worst of bartenders. Everyone disagreed, depending on what they were looking for in a bartender. But everyone agreed that I was a mess in those days. I still find it odd that I bartended. Most of my friends are surprised when I mention it. I never cared much for drinking, rarely spent time in bars, whether gay, straight, or questioning, but for a brief period of time in 1990, tending bar was what I did. I was thirty, back in school, going for another graduate degree I wouldn’t use. You might ask, as any rational person would, why I was trying for a third useless degree. Because I was dying, that’s why. That made eminent sense to me at the time. To my mind, it was a most rational decision.

In Lebanon in 1990, the civil war was ending with a mighty crescendo, fifteen years into a regional disaster that tore my country and my family apart. In San Francisco, we were still in the middle of the AIDS epidemic, a disease that killed many of my close friends, and within a few years would decimate an entire generation. Oh, and some four years earlier, in 1986, I had tested positive for HIV.

When I was informed of the news—the nice nurse sat me down in an oddly sized chair that made me feel like I was back in elementary school—I did what any rational person would do upon hearing that he had a short time left on this earth: I quit my nine-to-five corporate job, which was the last time I ever held one of those, and went on a six-month shopping spree. I’m sure I don’t have to tell you that the most therapeutic sprees are those where you buy nothing of any use. Since I lived in San Francisco, where the weather was moderate for three hundred and forty-five days of the year, I ended up buying stacks of cashmere sweaters. Which, of course, led me to pack those sweaters and move back to Beirut, where the winter was even milder than in San Francisco.

I wanted to be with my family because I was frightened and did not wish to die alone. I’d had to sit at the bedside of a friend as he slowly wasted away, alone because his family had disowned him, a vigil that many gay men and lesbians of my generation had to repeat over and over and over, sitting witness to a man’s death because his family refused to do so. I did not want that for me. Off to Beirut I went, my belongings stuffed in my exquisite, recently purchased luggage. I wanted to be with my family even though they were in the midst of a civil war. I sweated mightily as the bombs fell all about me because I was scared shitless. Or was I just too warm in cashmere?

I’d had to sit at the bedside of a friend as he slowly wasted away, alone because his family had disowned him, sitting witness to a man’s death because his family refused to do so.

A year later, I was back in San Francisco, still not dead but soon to be, I was certain. I sat myself down and told myself that I was almost thirty years old and that I should start behaving like an adult. Sure, I was dying, but I had to decide what I wanted to do with the short period of time left to me. In other words, what I had before me was a terribly shortened version of what did I want to do when I grew up.

So I asked myself, Rabih, I said, what would you do if you had one or two years left to live?

And I said, Get a PhD, of course.

So I asked myself, Rabih, I said, you have an engineering degree and a master’s in business and finance, what kind of PhD should you go for?

And I said, Clinical psychology, what else.

So I asked myself, Rabih, I said, how are you going to support yourself in school now that you’re not working and you’re in credit card debt hell because of all the fabulous cashmere sweaters you bought?

And I said, Why, bartend, of course. See? A most rational decision.

2.

To be completely honest, I did not consider bartending until a friend told me there was an opening for a bartender where he waited tables. I had done nothing comparable in my life, nor had I taken any drink-mixing classes, so I was hired on the spot at that odd establishment. My friend worked in a good old-fashioned diner where every other day the plat du jour was meatloaf (probably the same one). I, on the other hand, was hired to work in the bar upstairs, a faux upscale taproom with an English private club motif: leather fauteuils, pretentiously bound hardcovers in fake bookshelves, and port in the well. In a stroke of genius, the owners had baptized the place the Nineteenth Avenue Diner.

As the newest member of the staff, I was given the day shifts, the slowest. The bar did not have many customers, not at first. I mean, why would patrons of a diner want a spot of sherry or a tumbler of Armagnac after their good old-fashioned burger and fries? Even though I wouldn’t make much money, the situation suited me fine, for I’d discovered early on that working was not my forte. It took me less than an hour at the place to realize that I had to change some things in order to make the environment ideal for a person with my temperament. I could not remain standing for ten minutes, let alone an entire shift, so I moved one of the barstools behind the bar, next to the wall on one end, in order to be able to sit comfortably and indulge in my two passions, reading and watching soccer matches.

I don’t know why the owners thought an upscale English bar needed four television sets and a satellite system (to show British period dramas?), but I was grateful. I was able to figure out how to find all the soccer games I wanted to watch. For the first month or so, working that almost empty bar was as close to heaven as a job could get.

3.

I’d played soccer all my life. I used to joke when I first moved to San Francisco that I had an easier time coming out as gay to my straight friends than telling my gay friends that I loved soccer. Soon after I arrived, a friend and I started a gay soccer team, the San Francisco Spikes. In the beginning, all the team’s energy was directed to playing in what was then called the Gay Olympic Games, as well as other gay tournaments. By 1986, though, the Spikes had registered in a regular league, amateur of course, and by regular I mean that many of the guys on the other teams were homophobic bastards, or to use the Linnaean classification, assholes.

Even though I wouldn’t make much money, the situation suited me fine, for I’d discovered early on that working was not my forte.

Our team was terrible at first. We would lose by scores of 6-0 or 7-0. We were considered a mockery. A player on an opposing team, a Colombian who went by the nickname Chavo, used to gleefully celebrate each goal he scored against us by using the hand signs for fucking. He would go up to every player on our team, smirking, forefinger penetrating a hole formed by thumb and forefinger on his other hand. We ignored the taunting.

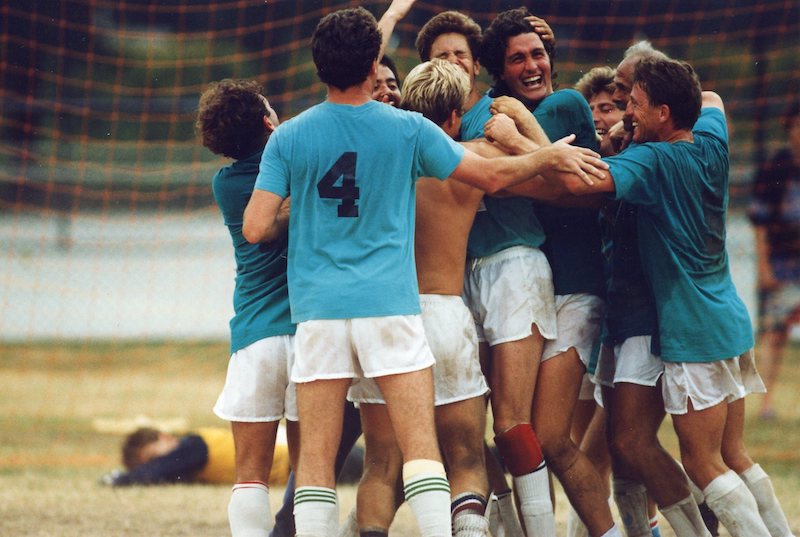

The goalie’s anxiety at the free kick when there’s only a two-man wall. Rabih Alameddine on the right.

The goalie’s anxiety at the free kick when there’s only a two-man wall. Rabih Alameddine on the right.

We began to encounter problems when our team improved. I believe it was during a game in the second season, against a team consisting of police officers, that we had our first bust-up. While the referee had his back turned, a cop sucker punched one of our players in the face. A hockey game broke out. For those of us who had been regularly confronting the police at ACT UP demonstrations, that was our first chance to fight back without getting arrested. No one received a red card. We won the game. Chavo, however, received a red card the next time we played his team. Toward the end of the match, we were leading by at least two goals when he slide-tackled me, taking me out. His cleats dug into my shin, my heels shot skyward. I thought my leg had been amputated. As I lay on the turf, Chavo, ever the gentleman, yelled, “I don’t want to get your AIDS, faggot.”

Usually, I would not have allowed an insult without some sort of witty comeback. I was a faggot, after all. Even something like “You’re not my type, bitch!” would have made me feel better. But I was writhing on the dry grass, in such pain that what I really wanted to scream was “I want my mommy!”

Chavo was kicked out of the match, which set a precedent. He would get red-carded in every game he played against us after that.

We came in third that season, won our division the next. Granted, it was not the highest division, but still. The fights lasted for a season or so before the league clamped down. They even sent a memo to all the teams stating that any player using the word faggot on the field would be automatically ejected.

Bless you, Mayflower Soccer League of Marin!

By 1990, when I began tending bar, the Spikes were one of the stronger teams in our division. We became just another regular team, except we looked better, of course, uniforms pressed and shirts always tucked in.

By 1996, half the players on the team had died of AIDS complications. Half the team, eradicated.

4.

I was leaning against the wall, slouched on my barstool, reading a long novel and minding my own business, when two frumpy-looking guys in color-splattered white overalls walked in. House painters, one presumed correctly. They plopped their hefty behinds at the bar, not at a table, which I hated, since patrons at the bar usually expected to be entertained by the bartender.

By 1996, half the players on the team had died of AIDS complications. Half the team, eradicated.

I knew I was in trouble when they asked, in a heavy Irish brogue, “Is the Guinness on tap?”

I pointed to the handle, which clearly stated Guinness in big white letters.

The answer to their second question was just as obvious. “Is that satellite?”

The third question was the most troubling: “Can we order food here?” No, no, no. These guys expected me to serve them, to actually work. How horrid. I should have kicked them out right there and then. The bar was a classy establishment, but it wouldn’t remain so if we allowed Irish guys to drink there. I should have dumped the canister of Guinness. The bar was supposed to be faux English, not Irish.

I had to abandon my stool, present them with a fake smile, and inquire, “What can I get you?” in a disingenuous tone that I hoped would come close to sounding as if I cared. I needed the job.

They ordered their hamburgers, which meant I had to sigh audibly, write the order down, and walk it all the way to the kitchen downstairs. They finished their meal, drank their Guinness, and left me in peace. They didn’t know what to make of me, so they didn’t engage, not that first day. They just made sure before they left that I knew how to work the satellite system. They told me—warned me, really—that they would return the following day to watch a soccer match. I groaned, they snickered.

Five of them stomped in the following day, loud, violating my space. When I didn’t put my novel down, I heard one of them say something to the effect of “I told you.” I held my finger up, both to order them to wait while I finished my chapter and to point to the television, where the soccer game was about to start. Thus began our tug-of-war: they would try to get me to work, or really just do something, anything, and I would try to get them to leave me alone. It was instant chemistry.

That day, one of them ordered something while the others pretended not to know what they wanted, forcing me to put in the order before another of them placed his. Back and forth, down the stairs and up the stairs, et cetera. I allowed that shenanigan just once. I also hated pouring Guinness, which was slower than molasses in winter, and then I had to wait for the damn thing to settle. The time it took for a pint of the dark concoction to come to rest was too long for me to keep standing but not long enough for me to return to my novel. They ordered their beers at different times, and boy, could they gulp them down.

By the third or fourth visit, they began a running critique of my bartending skills or lack thereof, particularly my complete incompetence at pouring Guinness, which was nothing like pouring other beers, as anyone with half a brain would know, they kept saying. Of course I had the best pouring technique: I tilted the pint glass to a mild angle, and with the other hand I flipped the bird at whoever was criticizing me at that moment. Another technique I learned quickly was how to say “Fuck off” the Irish way.

You’re doing it wrong.

Fockoff.

When one of them told me I should use an inverted spoon to spread the drip of the beer, I offered him a couple of suggestions on what to do with said spoon. I declared that there were as many right ways to pour Guinness as there were Irishmen in the world. I told them to walk over to an Irish pub, barely a block away, and harass their countrymen with their orders. No, they did not want to. They wanted to stay right where they were, and they wanted their Irish beer. Finally I’d had it. If they wanted their stout poured their way, they could bloody well come behind the bar and do it themselves. I could not be bothered.

Oh, they loved that. All at once, I became the best bartender, and they regulars.

The truth was that I was rude to them because I felt safe from the beginning. I felt at home with them.

I stopped resenting them for making me work once they started pouring their own beers, a win-win situation if ever there was one. And they were generous with each other. When they went behind the bar, they would always ask if any of the others wanted a top-up, and they’d even wipe up any spillage.

The truth was that I was rude to them because I felt safe from the beginning. I felt at home with them. I had gone to high school in England, and my closest friend at the time was Irish. These men were older than me, but we actually had a lot in common, which was obvious from the first soccer game we watched together. They had a sense of humor that matched mine. They could, and would, make fun of everything. Nothing was sacred, and I couldn’t tell you what a relief that was, living in the ever-earnest state of California, which had more sacred cows than all of the Indian subcontinent. They made fun of Americans, the French, the English, you name it. Boy, did they make fun of the English. They mocked Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and Muslims. No joke was out of bounds. They were ever self-deprecating. They tore into each other ruthlessly. And most of all, they made sure to insult me. I dished it right back, of course. I felt as if I were back with my family.

5.

Memory is the mother’s womb we float in as we age, what sustains us in our final days. And I seem to be desperately crawling on my hands and knees to get there. Lately, I can’t remember what I had for lunch yesterday or where I put my reading glasses. I finally sold my car in frustration because I had to look for it whenever I wanted to use it, never knowing where I parked it last. But what happened thirty years ago—that I can remember.

What bothers me to no end is that I can’t remember specific details about my Irishmen. I recall what happened, how they sat on the barstools, even some of the precise language used in our conversations. Yet for the life of me, I can’t remember their faces. I can’t tell you their hair or eye color, how short or tall. I’m unable to recall any of their names. I remember the name of another bartender who worked the evening shift because my guys could not stop making fun of it, Riley O’Reilly. They reserved their harshest mockeries for Irish Americans and their green inanities. I remember the names of my manager, of the waiters who worked at the diner. But not my Irish guys.

Incidents—incidents I remember clearly. I remember the Irishmen telling me a joke so good that I ended up sliding off my stool and lying on the perforated rubber mat, laughing my ass off. I remember this one time, the five were sitting in their usual spot and another customer was sitting on the other side of the bar. She was their age, appeared in good health except for a permanent tracheostomy. When I served her a third martini, she asked me to move closer so she could whisper, “If I faint, please call 911.” I was back to reading my book when I heard an immoderate thud. She was nowhere to be seen. All five men rushed over to where she’d been sitting. I leaned over the bar and saw her splayed on the floor. Luckily, one of the guys ran behind the bar, not to pour himself a Guinness, but to call 911. When the paramedics carted my customer off, the guys made fun of me for a week, suggesting I was too short to bartend since I could barely see over the bar.

It kills me that I can’t remember what they looked like. All my teammates who died, I remember. I still have team photos that I look at every now and then. I have nothing of my Irish guys. They too might all be dead now. When I walked off my job, it never occurred to me that I would one day wish I had some memento. It never occurred to me to plan against regret.

6.

I should take that back. I don’t remember all my teammates who died, not all the time. I had lunch yesterday with a friend who had also been on the Spikes since the beginning. I told him I was writing this essay, and we began to reminisce, about good times and bad. We began to go over all those who left us. We reminded each other of quite a few whom we hadn’t thought about in so long: the PhD student whom Thom Gunn wrote a soulful poem about; the best player we ever had, Phil, who played semiprofessionally in Australia and could juggle a ball in four-inch heels. I could barely see their faces in my mind’s eye.

So many of my friends died while the world remained aggressively apathetic.

I reminded my friend of an Ecuadoran who played with us for two or three seasons before succumbing. I don’t know why I think of Wilfredo so much, probably because he was such a character, a combination of terribly sweet and utterly strange. No matter what uniform we wore, he’d have the same top as the rest of us, but he declined to wear any shorts except his favorites, a pair of extremely tight red Lycra ones with no underwear. You could see that he was uncircumcised from the other end of the pitch. And he was a damn fine player too, just peculiar, more so than any of us. Most of the team was there at his deathbed to comfort him, his family having refused to have anything to do with him for years. I told my friend at lunch that I couldn’t remember Wilfredo’s face, couldn’t reconstruct it. How could we, he said, when we spent all our time staring at those shorts?

So many of my friends died while the world remained aggressively apathetic.

7.

To emphasize how odd the diner was, I should tell you this: Out of a waitstaff of maybe thirty, only three were gay. Before I worked there, we used to joke that “straight waiter” was an oxymoron, but no, that rare breed did exist.

A flamboyant African-American queen joined the staff some four months after I did. Let’s just say he tipped the fabulous scale so much that he made me look butch. Of course we hit it off, becoming work-sisters, coining ourselves Butch and Butchette. One day, it was Butchette who brought the Irishmen’s lunch order from downstairs. As he was leaving, he pulled himself up toward the bar, standing on the lower rung of one of the stools— he too was short—and puckered his lips. I dragged my barstool over, pulled myself up, and we sister-kissed, both lifting our left legs in the air, synchronized swimming without the water. We separated—he returning downstairs, I moving my barstool to its usual position—without saying a single word.

I tried to get back to my book, but couldn’t because the Irishmen kept staring at me.

“What?” I asked.

“Why did you do that?” they said.

“We’re friends.”

“He’s a poof,” they said.

Slow as I was, I only realized then that these guys had no idea I was gay. I should have noticed. They had been mocking practically everything about me—my looks, my height, my intellect, my going to school, my bartending, my Arabness, my not being Irish—but they had never brought up my homosexuality. They had no idea, which baffled me. I might not have been the most feminine of men, but I always figured that anyone who had seen me walk would recognize from a mile away that I was queer.

“I am as well,” I said.

“No, you’re not,” they said.

“I am too,” I said.

“No, no, you’re not,” they said.

“Oh yes, I am,” I said.

“No, you’re not,” they said.

For them to believe me, I had to use their language. “I take it up the ass,” I said.

“But you play soccer,” they said.

I returned to my book. They finished their lunch in silence. I knew they were shaken, or at least quite surprised, but I understood even then that they would not abandon me. It wasn’t only that they could pour their own beer (it wasn’t free; I trusted that each paid for what he poured). They liked me. They had always found me odd. Now they had to deal with my being odd and queer. They did come back, and boy, did they deal with it. It took them twenty-four hours, maybe forty-eight, but they returned with a litany of terrible, puerile jokes. Shouldn’t I turn my barstool upside down to sit? How many faggots did it take to change a lightbulb? Did I really nickname my goatee prison pussy? Was I a pain in the ass because I had a pain in the ass? Their mockery was relentless and relentlessly stupid. I loved it. As I already mentioned, we had quite a bit in common. Our emotional development had peaked in middle school. My jabs back were just as stupid if not more so. I told them that Bigfoot had a better chance of turning me on than any one of them, that I liked men, not cheap imitations, nor works in progress. The jokes would ratchet up in intensity when one of the waiters (not the waitresses) came up to deliver food since we had over-under bets as to how quickly we could make them blush.

They did not stop making fun of me until I was no longer there.

To this day, whenever I think of them, I begin to giggle all by myself.

We did not have any serious conversations about my gayness. I don’t think any of us were capable of it at the time. I remember once, about a month after they found out, one of them asked me if I was afraid of getting AIDS. I told him I was terrified. I was unable to say anything more than that, wasn’t sure I could explain such terror. How could I explain that I had night sweats, not from any disease, but from the fear of it? How could I tell them that my soul had already been crushed, that dread had shadowed itself unto my heart? I could not tell them I was HIV positive. It was eight years before my first book came out, announcing that fact.

8.

The World Cup was on that summer, and the Irish were in my bar almost every day, watching all the games when I worked. One Sunday there was an important second-round game at lunchtime, and the bar was as full as it had ever been, maybe twenty people, maybe thirty. I actually had to work. I made a rule that everyone had to follow: food orders were allowed before or after the game only. I was not about to leave a match to take an order down to the kitchen. My patience had limits, after all. About ten minutes before the start, I made sure everyone was settled. My Irish guys were in their usual seats on my left, already set with their burgers and Guinness. Some American remarked loudly that the announcers were unsophisticated because they called the game soccer and not football, as it was supposed to be called. My Irish guys let the poor, deluded thing have it. Football meant Irish football, as every enlightened person knew, and he should stop trying so hard to be anything other than the provincial yank that he was. Laughter, uproar, clanking of pint glasses.

I remember once, about a month after they found out, one of them asked me if I was afraid of getting AIDS. I told him I was terrified.

And in walked Chavo.

I wasn’t sure which of us was more surprised to see the other. His expression changed from stupid at rest, to shocked, to venomous. He hesitated a second or two before reaching the bar, but then he made his decision. He would proceed as his usual nasty self, bless his rancid heart.

“What the fuck are you doing here?” he yelled, loudly enough that the bar quieted.

I did what I always did when faced with a stupid question. What would I be doing standing by myself behind a bar, holding a wiping rag in my hand, surrounded by customers on the other side? Product modeling? My hands Vanna White-ing, On this upper shelf we have the vodkas and gins?

I just replied with a sigh, “I work here.”

“Heineken,” he ordered.

Why did assholes always drink Heineken? I placed a bottle in front of him, noting that it would not be his first drink of the day. I began to wonder whether he played soccer sober or not. I waited for him to pay, but he went off on a mini-tirade.

“They shouldn’t let someone like you work here,” he said. “This isn’t one of your neighborhoods.”

I expected one of my Irish guys to say something. From the corner of my eye, I noticed them drinking their pints.

“What if you give us your disease?” he said.

“Get the fuck out of here,” I said. “I’m not serving you.”

I took away the beer bottle, turned my back to him, and with a dramatic flourish poured the undrunk Heineken down the sink. He went nuts, high-tirade time. He was going to kill me. I was a lowlife faggot. He was going to jump the bar and break my bones. I was going to regret being born. I was about to order him to leave before I called the police when he quieted, and then I heard a scramble. I turned around and he was already at the door, stumbling out.

*

Soon after a threat dissipated, the terror always peeked out from behind the patina of bravura and camp. As much as I was loath to admit it, the motherfucker terrified me, on the soccer field or off. I had to control the swell of shaking, steady my breathing.

“What were you doing?” I yelled at my Irishmen when I was finally able to turn around without worrying that anyone would see the panic in my heart. The delicious comfort of rage flooded my veins in hot, resuscitating waves. “How could you allow him to come into our bar and say those things?”

All five were clutching the pint handles the same way, glasses in front of them in the same position, completely dry. They stared at me. I noticed just how menacing they looked, and it took me a minute to understand what had happened.

“We should explain the Irish Hello,” one said, holding the empty pint glass and punching the air as if it were a face. “Very popular greeting in Ireland.”

“We were going to kill the cunt.”

“We were so looking forward to painting his body black and blue.”

“The son of a bitch ran out as soon as he looked our way.”

“You may be a poof, but you’re our poof.”

“No one but us can call you faggot. That fucking faggot.”

I told them I had many witty insults to throw at them but I was going to give them a break for twenty-four hours. I would even pour them their Guinness myself, an offer they refused, anything but that.

9.

I stopped working at the bar not long after that. Never saw my Irishmen again. The diner and its taproom would shortly turn into a Chinese furniture store.

I didn’t get another degree. Somewhere along the line I would once again perform a one-eighty and reinvent myself again and again.

I did not die. So many friends did. I lost count of how many deaths I witnessed.

These days the San Francisco Spikes have about one hundred and fifty members. They field four teams in different divisions. I haven’t been able to play soccer in quite a while. These days I run or swim, solo activities.

I did not die and I did not recover.

__________________________________________

The preceding is from the Freeman’s channel at Literary Hub, which features excerpts from the print editions of Freeman’s, along with supplementary writing from contributors past, present and future. The latest issue of Freeman’s, a special edition gathered around the theme of power, featuring work by Margaret Atwood, Elif Shafak, Eula Biss, Aleksandar Hemon and Aminatta Forna, among others, is available now.

Rabih Alameddine

RABIH ALAMEDDINE is the author of the novels Koolaids; I, the Divine; The Hakawati; An Unnecessary Woman; The Angel of History; and the story collection The Perv. His novel The Wrong End of the Telescope was released in September 2021.