How the Writer Researches: Annie Proulx

John Freeman Interviews the Pulitzer Prize Winner in her Snoqualmie Valley Home

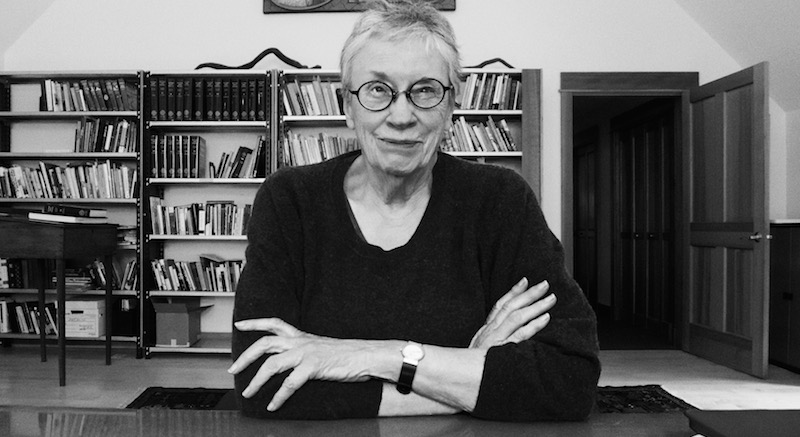

Annie Proulx is 80 years old and still not sure where she belongs. Standing in the atrium of her home in the Snoqualmie Valley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist eyes a photograph of the cottage she once occupied in Newfoundland, the setting of her 1993 novel, The Shipping News. “I fell in love with that landscape,” Proulx says, speaking in the tone of a woman describing an ex-lover.

“But ultimately, I did not belong there.”

After 20 years in Wyoming—several spent building a dream home she later sold—Proulx had a similar epiphany about that state. As she did about Vermont, and Texas, and New Mexico, and any number of places where she has lived. In an age of itinerary writer-teachers, Proulx’s boomerangs back and forth across North America are exceptional.

Now she’s made a similar discovery of the wooded idyll east of Seattle.

For months Proulx struggled to figure out why she was having reactions to foods she typically ate. At last she learned she was allergic to red cedar, the trees that rise up fragrantly around her house. Proulx laughs as she describes this, partly out of annoyance, but also because she moved to this home to finish her massive and extraordinary new masterpiece, Barkskins, a novel about climate change and landscape in which one of the book’s central characters is the forest itself.

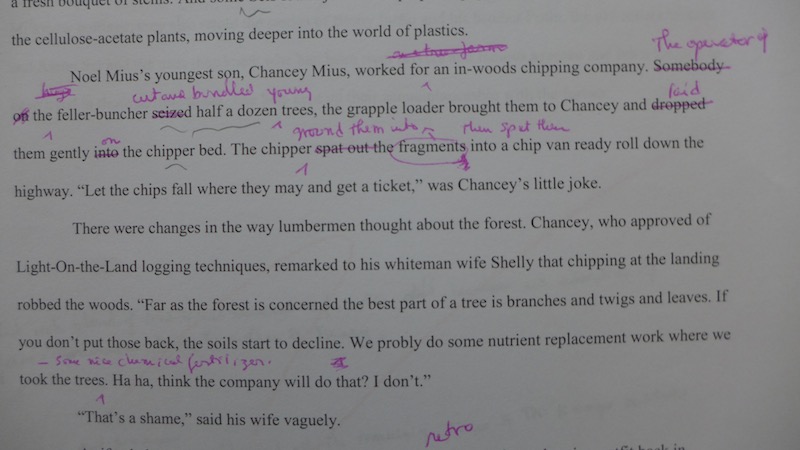

Barkskins, a slang term for lumberjacks, trails two families across four centuries—the Sels and the Duquets and their competing ways of making a living off the forests. René Sel, the paterfamilias of one clan, comes to New France in the 17th century as indentured labor and his offspring intermingle with Native Americans and toil in the dangerous tasks of felling timber and shipping it downriver to Penobscot Bay.

Meanwhile, the descendants of Charles Duquet (later changed to the less ethnic-sounding Duke) follow a different path, entitled by their God and Bible, they become land speculators, forever searching for virgin forests to chop down and turn into capital. They employ Native Americans to do the hard work.

Proulx’s own family likewise came to New France in dire poverty long ago and worked like the Sels. But she is not here to lay blame. What she wants is to show how it happened, to tell that story. “There was this massive, massive woods and only a few hundred people,” Proulx says. “Nobody was going to miss a few trees. You can’t work backward and start laying on blame. It just has to come as this is what was done.’’

The book is an enormous undertaking for a writer known for doing things the hard way. When Proulx became adored for tales of Vermont and Newfoundland, she picked up shop and moved to Wyoming for 20 years, learning the lore and mythology of the American West to a degree she still gets fan letters from cowboys and veterans returning home to it after tours of duty in Iraq. Now, though, with Barkskins, she has taken aim at two of the central mythologies of Americans and their landscape.

Moving upstairs to Proulx’s writing studio makes clear how seriously she takes this concern. Proulx sold the tens of thousands of books which once filled her Wyoming home; it was time, and it was painful. All that remains are a few hundred novels, some shelves of poetry—including the collected work of Les Murray—and shelf after shelf of books about landscape in North America, books like William Cronon’s 1983 classic, Changes in the Land, which describes the different notions of ownership Native Americans and colonists had about landscape.

Proulx spent years in these books, reading, as well as traveling to archives in Australia, New York, and also to the Waipoua Forest, where some of the trees are as many as two or three thousand years old. Over coffee in her large writing studio, surrounded by paintings and the remains of her research library, Proulx discussed why she felt this work necessary to making not just this book—but all of her books—come to life.

John Freeman: Barkskins begins in New France and moves through various parts of America. You’ve lived in many parts of North America; do you find that Americans have different attitudes towards landscape depending on where they are, or do you feel that we all descend from how white men treat the landscape as a resource?

Annie Proulx: I would say that’s correct. I don’t find that there are woods lovers around. There are some, of course, but the ordinary person thinks of wilderness in connection with a phrase “taming the wilderness.” That’s the way that Americans think of it. They also think there was once a primeval forest which of course is not true. Native Americans who lived in North America had plenty to do with the shaping of the forest, including setting fires every few years and sometimes big fires every 15 years to keep open parklike places where deer would come for the grass and meadow fare.

JF: In reading Barkskins, I was struck by how use of landscape in North America emerges so much out of a Christian idea of God and the dominion the Bible promises over Nature.

AP: You touched on something that nobody else has—the clue to the book is in the epigraph. Christianity is underneath our chopping of the forest and our doing what we feel we can do. Anything wild. Anything in the natural world. Wherever it is. Place has always been an interest of mine. I have a small library of books on place. A Dutch friend has recently done a fascinating review of Dutch topography. One of their major writers whose name is out of my mind at the moment wrote a fine book you might know called The Mountains of the Netherlands.

JF: No, I don’t

AP: Well, it’s a wry joke because there are no mountains at all. It’s below sea level. So the Dutch take a great interest in landscape.

JF: I had always been aware that global trade was very old—that it existed even before the Dutch East India Company. But Barkskins makes a sharper point on that score: that the growth of capitalism has always depended on the destruction of the environment.

AP: Yep. They are teammates.

JF: Was that something you knew well before you started to write this book and the research for it or was it something you began to read more about the history?

AP: I was well aware of it, believe me.

JF: As, having lived the life you had, read the books you have?

AP: I’m an observer. I was trained as a historian and landscape has been an interest for many years. You think, of course, “How did this get like this?” To look at paintings and landscape paintings of an early era—any place, Australia, the Hudson river, this part of the country—they weren’t making it up. That’s what they were seeing. And to think of what [the landscape] is now and how we got from point A to point X is rather terrifying. You could turn it into a story, which is essentially what happened there.

JF: What is your opinion of Bierstadt?

AP: [laughs] I like Bierstadt.

JF: I was thinking about this because I was reading John Williams’s novel Butchers Crossing before I read yours… and it made me miss the West even as its cover told me this was a book about how we imagine the West.

AP: What part of the West are you from?

JF: I was from California. Sacramento. It’s a different kind of West to the one where you lived. But there are assumptions about who you are and how you operate in the world which are different than those on the East coast. You take up space differently, speak more directly, interact at an angle. There are also different things about light and landscape, too, of course. Anyway, I remember seeing those Bierstadt paintings of the Sierras, and I felt like only an outsider could have painted them that way.

AP: Frederic Church is another great one on that score. I’ve got a book on those Western landscape paintings somewhere. I bought it for my sister but never gave it to her. It has gorgeous plates. It was done by an absolutely dreadful artist who did this one good thing by putting many landscape artists in between two covers. Bierstadt did a nice one of a mouse which I think is in Wyoming at the Bill Cody center. Just a mouse down in one corner of a large canvas. He’s looking us but I can’t remember what he’s looking at. Or she. Probably she.

JF: He used big canvases very well. Sometimes there were little things captured in corners. Looking at them, it was so easy to be distracted by a ray of light that felt godly. Meanwhile this other thing was happening.

AP: Have you ever seen those rays of light?

JF: Yes, and even the most stone cold atheist would have a spirit level experience.

AP: [laughs] Yeah.

JF: Have you felt trees over your lifetime as a living presence?

AP: I suppose so. My earliest memory in life is sunlight patterns on the ground coming down through the leaves of the tree. I remember that before anything else. That sort of sunk into me very early on. And my mother had a question she used to ask from time to time, sometimes when a piece of music was playing on the radio. Classical music usually prompted this question. She would ask, “What do you see when you hear this music?” And I always saw the woods.

JF: Is this the longest germinating book that you’ve had? It feel like it must be 20 or 30 years in the writing.

AP: More, I feel like it probably goes back to childhood. We saw great things. We did great things. We could go out and find trailing arbutus in the spring. We could find blood root. We could find lady slippers that are very rare now. They’ve all been dug up or destroyed but they were pretty common when I was a kid, which was a long long time ago. And so it sort of seeps in and if you could think back to your own beginnings it’s not that hard to keep going back. And I did wonder. So, I look at a lot of paintings. Paintings are very, very useful in thinking of landscape. I used paintings and other art frequently for getting the landscape right, getting the landscape somehow right.

JF: What else do you do to understand the gulf of history that you’re crossing to go back to characters? I know it’s all imaginary on some level.

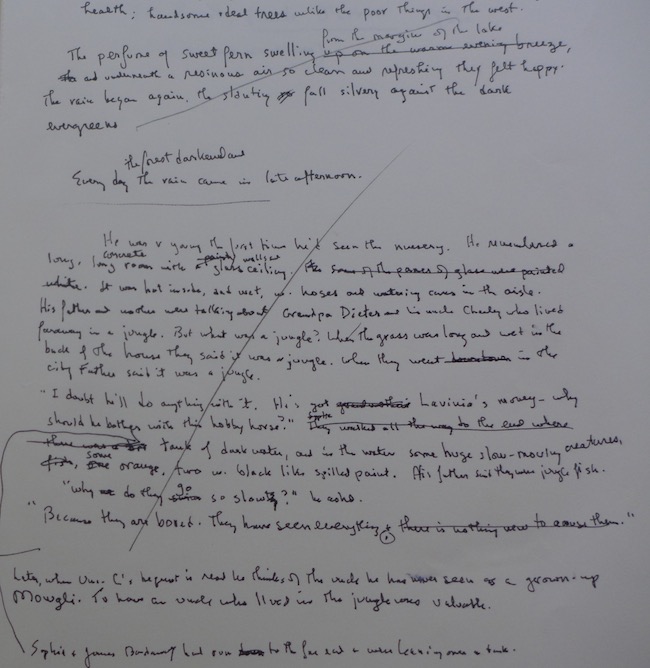

AP: It’s not all imaginary. As I said, I was trained as a historian, so what I do is really try to immerse myself in the period—for the food, the clothing, the music, the language, the slang…

JF: The songs…

AP: Yes, and old letters, to get an idea of the flavor of back and forth. There were years of reading that went into this book before I even started to write. I do that for each section of time I’m dealing with. When it comes time to write I feel like I’ve been living there for a long time in the period, so it’s no problem

JF: What does that feel like, to be outside of time rather than living through it?

AP: Unfortunately it’s become second nature so that I’m not ever in my own time. It’s extremely easy to slip into another period, another century with other characters and so forth. They just don’t go away. It’s lurking. It’s a kind of time travel. It’s very easy to do. It’s only annoying when you have to do things like take a plane or travel, deal with restaurants, or do anything in the real world. That’s very, very annoying

JF: Did you always believe the American Revolution began in the forests?

AP: No, I didn’t always believe it. Nobody else is going to believe it either, but I think a good case could be made for it. There were untold numbers of incidents of the sawmill owners, and they were the ones who were really set against the domination of England and the heavy handed taxes that were passed down. So this is something to be explored. I’m sort of hoping that some grad student will take it up and notice that the Tea Party was the Tea Party, but the real action that went on for decades and decades was in the forest. It wasn’t the tax on tea that really excited peoples greed and action and animosity, but the fortunes that were being made and denied the woodcutters, the millers. It was really the saw millers. These guys were buying up vast tracts of land and away they went.

JF: Quite a few of the people meet their ends very quickly in this book. One man thinks a tree has fallen on him, when he is clubbed over the head. Lights out. Is this just the way life was?

AP: That’s the point. Yes. That is how life was. There were plenty of what we would call today accidents. It was a more dangerous time to live. Lots of things could go wrong. And when you have people who would constantly use axes for whatever—people would whittle with them and make little small things and so forth—you’ve got a recipe for a lot of blood.

JF: But the deaths I feel in this book just as strongly are that of the trees. This book has completely changed the way I think I’ll look at forests.

AP: Good, you see the stumps now.

JF: Yes, it’s like seeing corpses.

AP: Yes, it is like seeing corpses. And for me, living in the Rockies was like watching the death march because about 15 years ago, the trees started to turn red. We had some very hot, dry years, and in came the bark beetles, and the trees began to die. Whole mountainsides turned red and then gray. And this was not noticed outside of local people. People in other parts of the state that didn’t live near the mountains didn’t notice it, so they didn’t worry about it. And people on the East coast had not a clue that this was happening, but it was one of the nice little side effects of global warming. The Rocky Mountains will be something else before long. A nice, low shrubby aspect in years to come. It’s happening fast. And that got me thinking, 15 years ago, about this book. And about the disappearance of something that was believed to be permanent. That’s another thing the book tries to express: there is no permanence in the natural world, at least thanks to us.

JF: Do you think you’ll write short stories after this? At some point?

AP: I was thinking I might try and see if I can still write a short story. It’s just such a different mindset from writing a large novel. So different that you almost feel like a different person sitting down to make one. I don’t know if I can still do it.

JF: Your stories are all almost like novels themselves. It must take a lot of force to compress that hard.

AP: I’m really pleased to hear that. I do a lot of chopping with short stories. I just trim, trim, trim, trim. Take more out so more can go in. The New Yorker is running a war story from those Wyoming stories. I occasionally get vets who come up to me. Rural veterans, not urban guys or suburban guys, but guys from the West who know the land and the way people and families work there who appreciate that story and say: you got that right. Which is always very nice, when people get it: get the inside of the story instead of the plot.

JF: I’ve noticed traveling out here, the airports are as full as ever of marines and returning veterans.

AP: And there’s also a stronger thread of brotherhood that’s running through all of these returnees that wasn’t there after World War II. Those guys were glad to get back and get to their families. The thing now is that there aren’t any jobs, and it seems to be a lot of bad stuff that’s happening—one can almost see it like a thin spool of thread that’s been unstrung and snags each one. It’s a brotherhood of misery. It’s not unlike wood cutters and sailors of an earlier age. All dreadful jobs.

JF: Barkskins has a huge population of these guys, the cutters—are they based on anyone you’ve met?

AP: I collect pictures that I’m going to use sometimes for characters because their faces are so arrestingly powerful.

JF: [Looking at the face of a man in a newspaper clipping] What a great face.

AP: Yeah, if you had to write that face, it takes something…

JF: There are a lot of men with thin mouths in this book.

AP: Yes. Here’s a quick little thing about the drunken tree… [shows another newspaper clipping] This guy looks so mean. So incredibly mean and just ruined, he looks like a hopeless case. I don’t think I could write him.

JF: There’s no light in his eyes.

AP: No kidding.

JF: Do you always work longer and then do a lot of cutting, like with stories?

AP: I guess that’s so. Unless it’s the other way around sometimes. It varies. I do often write very, very tightly from the beginning and then have to add in. So I would say it’s about 50-50. Sometimes I write too much and have to cut, but more often I write too tightly and have to fatten.

JF: How do you know when you have to fatten?

AP: You just feel it.

JF: So it’s about shape. Or balance?

AP: It’s about something intangible actually. Shape is good, balance is good, but it’s not whether it fits with something else. It’s about piquancy.

JF: You do have a background a little bit as an amateur chef of sorts.

AP: I went to cooking school. I like to eat, so I learned how to cook.

JF: Where do you think you’ll go from here, back to Vermont?

AP: I went to Vermont recently for three weeks—ostensibly to visit my sister but also to see if I could find a house or could live there again or if it made a difference in the allergies. It did make a difference in the allergies. I had a good time visiting my sister. I don’t think I could live there again. I left 20 years ago because I was tired of something; I can’t even say what. Part of it was the ruined landscape. People would gleefully tell you there are plenty of woods around, but it’s just grubby stuff. It’s not like it was at all. And so much has changed. Now it’s loaded with Lyme disease bearing ticks and black flies which are further south than they ever were when I lived there. So the ticks have come up and black flies have come down and it’s a different place and people are interested in things that I’m not interested in at all. Been there. Done that. So as much as the red cedar bothers me, I like this part of the country. I don’t like Seattle because of the traffic and craziness and because of the huge disparity in income. But I like the peninsula. I like the plants and animals. I like the landforms. I like the trees that have escaped annihilation. I love the rivers. It’s just a place that interests me a lot. So I don’t know what I’m gonna do, whether I move or not. I should definitely move out of here because every tree out there is a red cedar.