This September, I’m using my 5th-grade Trapper Keeper to organize my novel revisions. Less than 24 hours after I was catapulted back into the neon 1990s world of Lisa Frank, I opened the August 25th Sunday Times and learned that E. Bryant Crutchfield, inventor of the Trapper Keeper, had just died at 85.

When I shared the news on social media with literary contemporaries—early millennials and Gen Xers—my phone exploded. According to artist and New Yorker cartoonist Adam Douglas Thompson, who grew up using Trapper Keepers in Maine, Crutchfield’s design was “the quintessential 80s visual aesthetic.” James Tate Hill, author of Blind Man’s Bluff and a shrewd writer on pop culture, described Crutchfield’s binder as “the centerpiece of back-to-school shopping” in those days. Even so, I was surprised by the level of devotion.

Oh, the crisp sound of the Velcro latch, the sweet tang of new plastic! And the indelible images of laser beams, planets, the California Raisins, neon rainbows, musical notes, kittens and unicorns. Why did this product, with its wide range of designs, capture our generation’s imagination?

Crutchfield was clever. He saw the Trapper Keeper as a practical tool, but also as an artistic canvas, a way for kids to have a voice in school. Writer Jennifer Baker, also the creator and host of the Minorities in Publishing podcast (https://minoritiesinpublishing.tumblr.com), “didn’t fight it” when her mom got her the girly heart and unicorn styles. But she preferred plain Trapper Keepers that she could design and modify. “The binders and backpacks became a signifier of our personalities,” Baker recalled.

Hill also chose Trapper Keepers with solid colors because he was insightful enough to anticipate his taste changing. “I never had any of the themed Trapper Keepers—The A-Team comes to mind as one my friend had—because even in my youth I feared I’d outgrow a show or cartoon before year’s end and then be stuck with Mr. T’s scowl every time I reached into my desk.”

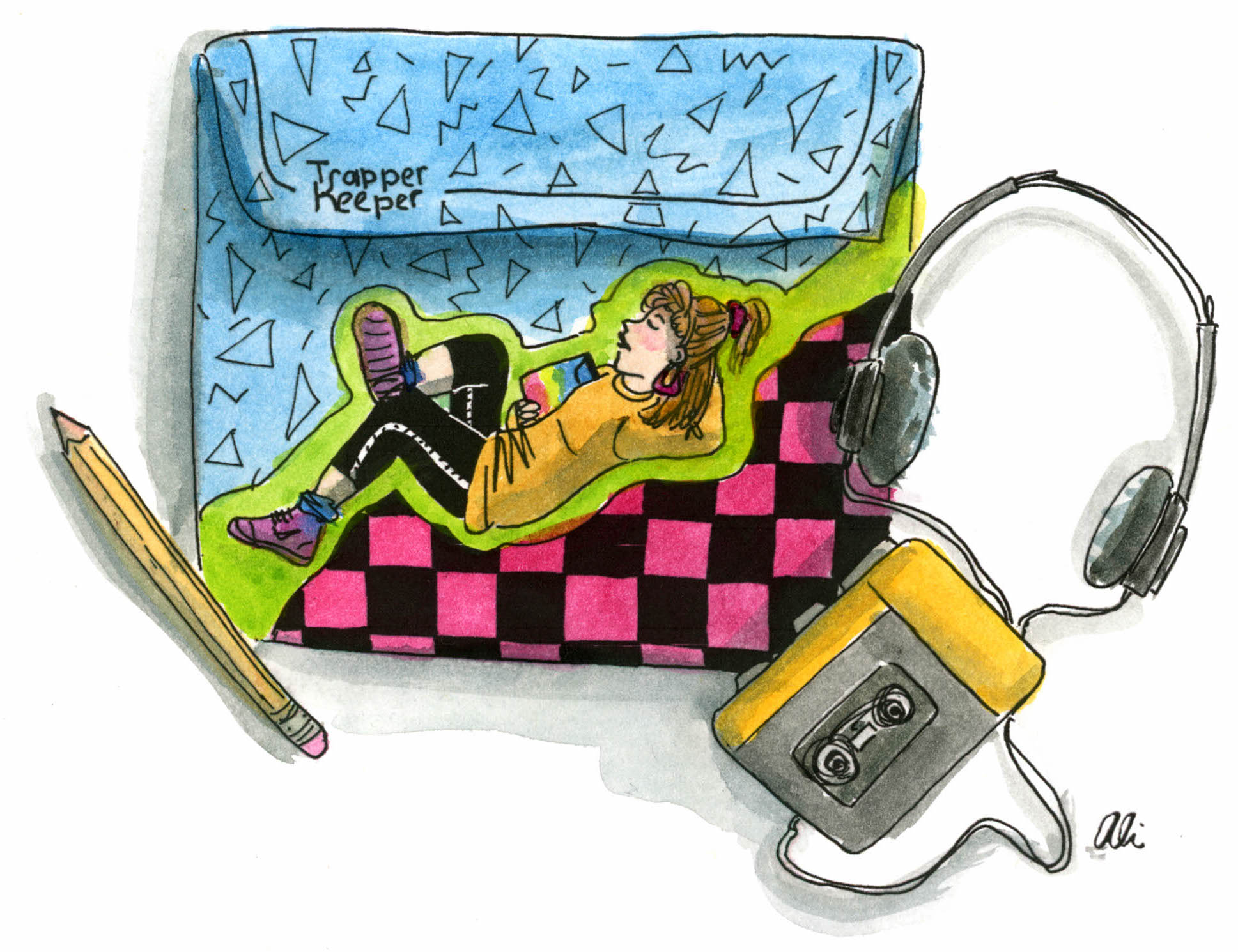

Illustration by Ali Solomon.

Illustration by Ali Solomon.

The New Yorker cartoonist and author, Ali Solomon, whose new humor book, I Love(ish) New York City, comes out next month, describes Trapper Keepers as a way to make a “loud statement” and stand out. Solomon wasn’t thrilled with her own discounted, off-brand version. “I think they were called something like the Trappee Keepee,” she quipped. But she was mesmerized by her folder designs of neon triangles and Garfield the Cat. Through the repetitive practice, Solomon’s own cartoons and voice as an artist emerged.

The Mead Corporation reported selling more than 75 million Trapper Keepers (and counting) to our generation.In his small-town Arkansas school, the writer Paul Crenshaw remembers kids lingering in hallways between classes to sign each other’s Trapper Keepers, decorating them with sparkly stickers or pens: “What design you picked, that was like your avatar image.” Crenshaw, whose forthcoming essay collection will explore the Cold War and 1980s pop culture, helped me understand the personal significance of the Trapper Keeper. When I was interviewing people about their school supplies, I was really asking how they felt about themselves during their vulnerable adolescence.

What exactly is the “Trapper Keeper generation”? The late 1970s through early 90s, by most accounts, but the boundaries are fuzzy. When I reached out to potential Trapper owners, I didn’t google anyone’s birthday or try to pin them down by year, but some generational patterns emerged.

If you owned a binder with a snap, or the cover image featured a beige Critter Sitter, you were likely born closer to 1970. People with the Velcro, zipper, and Lisa Frank style were 80s babies. (Of course, this is a highly imprecise measure as some people inherited older siblings’ or old second-hand Trappers). Some authors lamented missing the boat on one style or another because they were born a little too early or late. There were many missed Trapper Keeper connections..

Patricia Park, author of Re Jane (Penguin, 2016) and the YA novel, Imposter Syndrome, forthcoming from Crown in early 2023, had a used Trapper Keeper. “I was the youngest of three, so I got a hand-me-down,” Park noted. “An ugly geometric drawing! For my parents, it was all about utilitarianism. It defeated the purpose of the Trapper Keeper.”

Set in the present day, Imposter Syndrome features Alejandra Kim, a Korean-Argentine teen navigating identity politics, performative wokeness and grief at a progressive prep school she dubs “Quaker Oats.” I see flickers of Park’s Trapper Keeper frustration in description of Alejandra lugging around an ancient laptop that needs to be constantly plugged in because its battery lasts only five minutes. What we carry in our backpacks can reveal so much about family circumstances, privilege and belonging.

Of the thirty people I interviewed who were raised in America, 28 responded “yes,” they had a Trapper Keeper, and had a lot to say. But there was one author who didn’t have a Trapper Keeper growing up, but still sent me a page-long email about not owning one. I’ve known the novelist and poet Bushra Rehman for twenty years, and have heard and read many tales of her childhood in Corona, Queens, where her father helped found one of the first Sunni masjids in New York City. When I received the long email about Rehman’s relationship to Trapper Keepers, I gained a whole new window into my friend’s life.

When I look hard at Lisa Frank’s yellow dogs, bright as highlighter pens, I feel unsettled in a way I can’t pinpoint.Rehman shared that, although she saw Trapper Keepers advertised, and understood what they meant to kids, she didn’t think of them as a possibility in her religious Pakistani-American family with five children. Cost was a factor, but her feeling of distance from pop culture was even more profound. “There was our world, the world of Queens in the 80s and the world of sitcom TV where the Trapper Keepers lived. This sitcom world was the other America, white and suburban. In my America, I had a denim binder I loved, the way I loved my favorite pair of jeans.”

I delighted in Rehman’s reflections, which got me even more jazzed up about her highly anticipated queer coming-of-age novel, Roses, In the Mouth of a Lion, to be released by Macmillan this December. Like Rehman, the New York Times “Modern Love” columnist. Sara Glass grew up queer in a strict religious community (in her case, an Orthodox Jewish family in Brooklyn with seven children). After reading her writing, I imagined that her upbringing didn’t expose her to many trends. But she responded “Of course I had a Trapper Keeper!” Her taste was firmly grounded in the unicorn and puppy covers, not scantily clad pop stars that others owned, so Trappers were a mainstream fad she participated in.

Kyle Lukoff, a children’s and YA writer and National Book Award finalist, acknowledged that he was born in the “height of the Trapper Keeper era,” but didn’t partake because, to paraphrase him, “babies don’t use binders!” Sassafras Lowrey, who uses the pronouns ze/hir, was born the same year in the same region as Lukoff (the Pacific Northwest), but had a different take:

“I’m 100 percent the Trapper Keeper and Lisa Frank generation (I was born in 1984 :). I was a complete Lisa Frank fanatic in the 90s and actually JUST earlier this month purchased the re-released Trapper Keeper for organizing some of my book/writing work, LOL, + I actively use Lisa Frank stuff as part of my writing life (not to mention the rainbow wall in my writing office).”

Trapper Keeper conversations served as a jumping off point for remembering music, food—and our whole lives. “When you asked me about Trapper Keepers,” Park said, “I instantly thought: New Kids on the Block, Capri Sun, and Lunchables. Oh, and snap bracelets.” I hadn’t thought about my favorite band, T.L.C. and the song “Waterfalls” for many years, but when Park mentioned New Kids on the Block, I remembered my ambivalence towards them and Hanson. My preference of the girl rappers we described as “tomboys” was an early indication I was queer. I didn’t know it at the time, and would wrestle with labels through my forties, but my school supplies told the truth.

Lowrey, who writes “gritty queer punk novels, and books about life with dogs,” remembered owning a Lisa Frank’s “Princess Pearls “…a long haired dog that I decided was a Lhasa Apso… I also had one with… the Golden Retriever duo eating a “pup cup” long before Starbucks started giving us whipped cream cups for our dogs.” Now Lowrey is a certified dog trainer and expert in pet care—and the only current Trapper user I spoke with.

This week, Staples sent out an email reminding us that the “iconic” Trapper Keeper is back on the market with retro styles. They go for $15. If you want an authentic 90s model, you can also spend upwards of $500-$700 for a rare Lisa Frank (which might not even function) on sites like Etsy and Poshmark. When I tried to remember where I bought my original Trapper, I looked up the year the Staples superstore was founded—1985—and wondered if the chain was founded partially in response to the Trapper craze. Nowadays, many physical Staples stores are closing.

In 2022, we all seem caught in limbo between digital and paper worlds, leaning more towards digital. But we all feel some dissatisfaction at this reality, and nothing has replaced the Trapper’s role in our lives. “If they marketed something new, an organizer for our generation, I would line up to get it,” Park said.

Leona Godin, author of There Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness (Pantheon, 2021) shifted to accessible digital note-taking as a young adult who was slowly losing her sight. But she missed the analogue, 70s Star Wars Trapper Keeper days. So she purchased paper psychedelic notecards to use with her pistachio green slate and braille stylus. The process of creating braille dots is slow, but “tactilely pleasing.” At least the notecards give her a “whiff of aged paper” that take her down memory lane.

Nostalgic as we all may be, I wonder if there was any dark side to the Trapper Keeper trend? Lowrey tipped me off to a disturbing Twitter outburst from Lisa Frank where she was defensive and nasty after stealing images from Amina Mucciolo, a Black, queer, autistic artist. Deeply disappointing.

It’s hard to put that incident into any context because Frank is so private, refusing interviews and photographs. In one video interview, Frank’s face was obscured and she sat in darkness. Her voice sounded the way I imagined: crackly, raspy, deepened by smoking or exhaustion.

Frank has long lived in seclusion in the Arizona desert. In its heyday, her 320,000-square-foot factory in Tucson (on S. Lisa Frank Avenue), employed 500 workers and gave tours to school kids. Now it’s empty and abandoned, weeds choking the rainbow walls and fence decorated with Frank’s trademark musical notes. When a student journalist knocked on the door in 2013, she spied a giant Golden Retriever and big-eyed teddy bear in the lobby. An employee met her at the door to tell her that tours were canceled. She was only one of a handful of employees rattling around the vast space. Now the only tenants are the colorful figurines.

When I look hard at Frank’s yellow dogs, bright as highlighter pens, I feel unsettled in a way I can’t pinpoint. Researching her characters, I learn they are all named after her pets and family. The rainbow leopards, Forrest and Hunter, grew up alongside her namesake sons, whom she claims took on personality traits of the preexisting cartoon characters that she’d invented. Creepy? I’d say!

I learned that the hummingbird emblazoned across my vintage Trapper has a name, Dashly, and a favorite color, “Fantastic Fuschia.” Flitting around gardens, “she might take a sip of the delicious fuschia nectar, or she might hover… to enjoy the Fantastic Fuschia fragrance which is sweeter than any perfume you could ever smell …” I felt like a hummingbird myself as I wrote this piece, but not all memories I sipped were sweet. What dark corner of my psyche responded to the ruined factory that trapped toy animals, or the empty windows reflecting an electric desert sky?

As I pondered this, Diane Zinna’s hallucinatory, kaleidoscopic novel, The All-Night Sun (Random House, 2020) looped through my mind. Exploring Sweden’s blazing midsommar when the sun never sets, girls wear flower crowns and romp through fields of “immense pink and purple lilacs.” Grief is at the center of the novel, but Zinna’s prose sweeps you away in sizzling neon energy. “Am I right in that there’s a Lisa Frank energy here—crazy color and loneliness?” I asked Zinna, who teaches my Grief Writing class on Zoom.

“I associate that whole era with being a latch-key kid,” Zinna said, noting that she strongly identified with the Frank aesthetic. “It was a wild and free and lonely time.”

The Mead Corporation reported selling more than 75 million Trapper Keepers (and counting) to our generation. So we must have been wild, free and lonely together.