From This Year’s Cundill History Prize Shortlisted Title All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tiya Miles.

“Well now, what about us, the women who were sitting here in Mt. Zion Church, the women coming after our great ancestresses? WHO OF YOU KNOW HOW TO CARRY YOUR BURDEN IN THE HEAT OF THE DAY?”

–Mamie Garvin Fields recalling a speech by Mary Church Terrell, president, National Association of Colored Women, in Charleston, 1916“Still there are seeds to be gathered, and room in the bag of stars.”

–Ursula K. Le Guin, Dancing at the Edge of the World, 1989

*

African American things had little chance to last. This is a painful lesson learned by family historians and museum curators. How could people who were property acquire and pass down property? How could families auctioned like cattle hold on to a Bible or a bead? An excess of trauma, a glut of disruption, and a surfeit of sudden migration severely limited the chances for enslaved people to maintain troves.

Cast into a faulty freedom following the Civil War, without the benefit of savings or stockpiles, formerly enslaved parents and children often lived hand to mouth, desperate to fend off crushing debt peonage. They lacked land, animals to work it, and tools to aid in their labor. They could claim few personal items beyond “the clothes on their backs.” The modicum of things Black families did manage to acquire and hold on to were accorded little value by outsiders. Compared to other groups with a stability afforded by earnings, wealth, or racial privilege, Black people’s possessions were more likely to wind up in dump pits and rag bins as families lost elder members, moved on, or were pushed out during the height of Jim Crow segregation and racially motivated violence.

“There are so many stories about the objects that were lost,” the family historian Kendra Field has noted, “lost letters, lost photographs, lost objects of meaning.” When African American things are lost, the stories once joined to them weaken, memories of the past fray, historical evidence shrinks, and intergenerational wisdom fades.

This loss of the material traces of history, which stands alongside a multitude of other losses in African American experience, has grave ramifications for well-being. Human values and human relations have been expressed and revealed through things for as long as we have been painting on cave walls and making tools. We come to know ourselves through things, cement community ties through things, think with things, and remember what is important to us with the aid of objects.

Beyond the critical role of communicating information, things function as tokens and repositories, as staples in the fabric of time, as a means to effect psychological, emotional, and existential transport or to “convey viewers to another world or state of being.” This quality allows people to use things in the service of compassion and communal life. When we see, touch, and consider another person’s cherished object, we come to appreciate their experience and their group’s experience that much more. In this way, the physical materials that we find, preserve, or make (from rocks and shells to books, blankets, and buildings) can function like social glue, adhering individuals to one another through felt relationship.

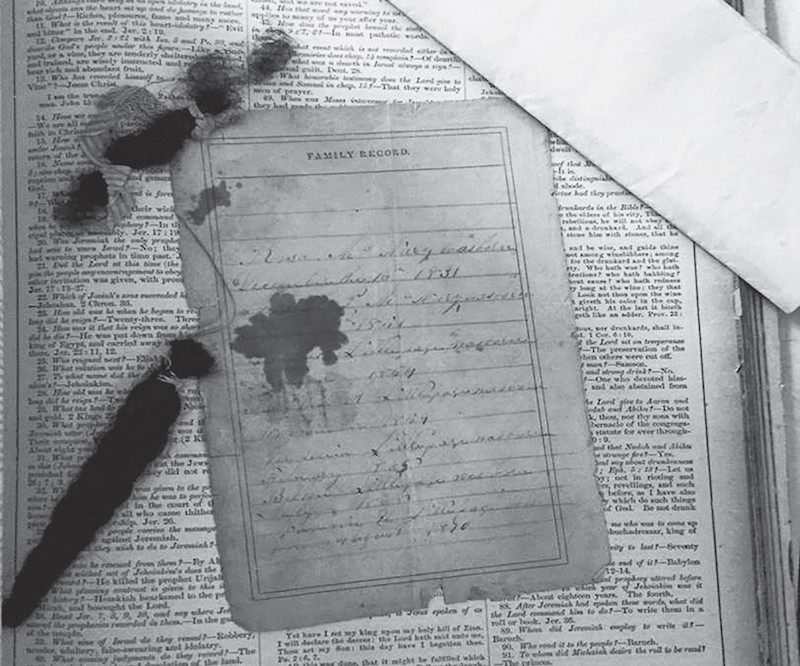

Interior page of the Morton family Bible. Aaron and Gardenia Morton used this family Bible as an archive, storing inside its pages hair clippings, lists of births and deaths, and funeral announcements. The parents of seven children (two boys and five girls), they passed the Bible down across generations. It remains a family keepsake today. Family story shared by Jessica D. Moorman. Photograph by Tiya Miles. Used by permission of Jessica D. Moorman.

Interior page of the Morton family Bible. Aaron and Gardenia Morton used this family Bible as an archive, storing inside its pages hair clippings, lists of births and deaths, and funeral announcements. The parents of seven children (two boys and five girls), they passed the Bible down across generations. It remains a family keepsake today. Family story shared by Jessica D. Moorman. Photograph by Tiya Miles. Used by permission of Jessica D. Moorman.

Beyond connecting people, things contain their own vitality, profusion of spirit, or even, we could say, personality. We recognize how many things in our daily lives were once (and are still?) alive when we consider the way in which materials (building supplies, clothing, glass bottles, and so on) are harvested from the living earth. We sense this strange quality of seeming aliveness when certain things capture our notice (a pearlescent button winking in the sunlight, a porcelain doll with perceptive eyes, a sculptural acorn poised like a dancer, a four-leaf clover lying in wait).

Particular things can affect our thoughts, moods, and movements, as if they are acting in the world. Enlivened things can call us into recognition of a material world that exists independently of the human sphere of action but also intersects with our lives. Cultivating a consciousness of this vibrant physical realm and a recognition of the ethical and primal implications of our interdependence with it may “chasten fantasies of human mastery” over nature and other people. It could help us find ways to live differently than we have since the industrial revolution, which has so badly damaged this physical planet.

Having been treated as possessions and deprived of ownership of themselves, their families, crops they nurtured, and objects they made and maintained, African American survivors of slavery recognized the world of things. They lived each day in haunted awareness of the thin boundary line between human and non-human, a thinness daily exposed and abused by slave societies. Despite the prominence of a Cartesian duality in Western philosophy that proposed a clear split between spirit and matter, enslaved Blacks knew that people could be treated like things and things prized over people.

Awash in this awful knowledge, African Americans may have been early theorists of the mercurial nature of things. In this understanding, they would have joined Native Americans, the first thing-thinkers on this continent who affirmed in their stories and lived through their actions a belief that many things have a kind of spirit and are capable of relationship. In their everyday lives, Indigenous North Americans recognized the animated nature of things as well as the innate relationality of people, non-human animals, and plants, all of which, scientists now confirm, share common fundamental elements (such as cell structure, chemical makeup, and DNA).

African Americans may have been early theorists of the mercurial nature of things.In addition to enslaved people’s knowing all too well the metaphysical quality of things that went deeper than the bare necessity of what was needed for survival, comfort, honor, and social connection, their understanding of the role of possession and possessions in their own subjugation motivated their desperate attempts to acquire and retain things of value. Objects became “weapons” in the ongoing struggle for dignity and liberty. Enslaved people used “coins, cloth, drams of liquor, [and] battered top hats” in pursuit of freedom and purpose. For them, things amounted to a real world of provision and beyond that, to “‘dream worlds’ of material possibility.”

Material objects performed many functions in the lives of Black people and, indeed, all people, from the practical and economic uses of items to the mental and emotional meanings of things. A heart-rending letter written by a man sold away from his family reflects this understanding of the material, social, and psychological importance of things.

“My Dear,” Abream Scriven penned to his wife, Dinah Jones, in the fall of 1858, “I want to Send you some things but I do not know who to Send them by but I will try to get them to you and my children. My Dear wife for you and my children my pen cannot Express the griffe I feel to be parted from you all.”

Abream hoped that these things he possessed and touched, when received and held by his family members, could help fill the gulf of sadness that separated them. In another missive, dictated by an enslaved woman in Missouri named Ann to her husband, Andrew Valentine, a soldier in the Civil War, things represented remembered ties and a vision of freedom.

“You do not know how bad I am treated,” she related. “They are treating me worse and worse every day. Our child cries for you. Send me some money as soon as you can for me and my child are almost naked. My cloth is yet in the loom and there is no telling when it will be out. Do not fret too much for me for it won’t be long before I will be free and then all we make will be ours.” Ann concluded the message to her husband with this postscript: “P.S. Send our little girl a string of beads in your next letter to remember you by.”

Elizabeth Keckley, the formerly enslaved dressmaker to Mary Todd Lincoln, emphasized the relationship between memory and things at the close of her memoir: “Every chair looks like an old friend. In memory I have travelled through the shadows and the sunshine of the past, and the bare walls are associated with the visions that have come to me from the long-ago. As I love the children of memory, so I love every article in this room, for each has become a part of memory itself.”

For Keckley, the things she owns and lives with seem to store her memories, releasing them to her when she seeks them out while triggering emotions of affection, melancholy, and determination. This may, in fact, have been similar to the ensemble of emotions that flooded Ruth Middleton’s chest when she touched and inscribed her grandmother’s sack. Things awakened memory and inspired feeling as well as action. Keckley felt moved to recall and write with the aid of the things in her room. Ruth felt moved to stitch the sack and list the things once packed inside it.

For each of these survivors of slavery or its legacies (and, indeed, for all of us), things possess the ability to house and communicate “the incorporeal”: emotions like love, values like family, states of being like freedom. And more than that, Elizabeth’s walls and Ashley’s sack may have felt alive and actively present to their caretakers. There is a sense in these women’s reminiscences of a “spiritual imaginary of matter,” a mental and even metaphysical space in which things incorporate, maintain, and release a psychic or spiritual quality.

In their writings quoted above, formerly enslaved people mention hard, relatively durable things such as chairs, walls, and beads (the last item being a recurrent one that Black as well as Indigenous enslaved people sought and gifted to one another), but they also touch on textiles, as did many of the enslaved in interviews and narratives published from the 1840s to the 1930s. Fabric—like the cloth still unfinished in the rungs of Ann Valentine’s loom—stands out for its symbolic resonance in the history of African American women, enslaved or free, and women across boundaries of race and class.

In these distinctive features, cloth begins to sound like this singular planet we call home.Ann chose this cloth, and the process she undertook in making it, to convey to her husband the poverty of her domestic circumstances and also to lift his spirits with a vision of hope for their future. The cloth she wove was as fragile as their lives and stretched thin like their familial connections. Yet one day that cloth would be complete and counted as the family’s property, softening the financial hardship they endured. And we can imagine, if that day came and Ann Valentine did finish her cloth, that she may have handed it down to the child she mentions in her letter. That child, and that child’s children, might have used the cloth from Ann’s loom as a table or bed covering into the 1900s, recalling through the object, through its warmth and its worn-in softness, the story of their family’s love and persistence.

As a pliable and fragile type of thing, fabric uniquely conveys psychic meanings hinted at in Ann Valentine’s desperate correspondence. The constituent parts of a textile—filaments woven, knitted, or fused—are countless elements made into one. Fabric therefore represents the connectedness of many threads that together create a whole cloth. It weakens over time through repeated use, washing, and sun exposure, lending it a quality of delicacy requiring care. Because of this innate multiplicity and natural fragility, cloth has stood for people across time and cultures. It symbolically represents our own bodies, our temporal lifelines, and our social ties to one another.

The association between fabric and human life is only strengthened by our propensity to drape our days and nights in this material. At birth, in death, during sickness, and through religious ritual, we coexist with fabric. We wrap our bodies and our most intimate moments inside textiles, which accounts for the emotional effectiveness of projects like the 1980s collaborative AIDS Quilt. Requiring caretaking and at the same time providing solace, “textiles are often mobilized in the face of trauma, and not just to provide needed garments or coverings but also as a therapeutic means of comfort, a safe outlet for worried hands, a productive channel for the obsessive working through of loss,” explains one art historian.

Fabric is a special category of thing to people—tender, damageable, weak at its edges, and yet life-sustaining. In these distinctive features, cloth begins to sound like this singular planet we call home. Cloth operates as a “convincing analogue for the regenerative and degenerative processes of life, and as a great connector, binding humans not only to each other but to the ancestors of their past and the progeny of their future,” fiber artist Ann Hamilton has written.

“Held by cloth’s hand,” she continues, “we are swaddled at birth, covered in sleep, and shrouded in death. A single thread spins a myth of origin and a tale of adventure and interweaves people and webs of communication.”

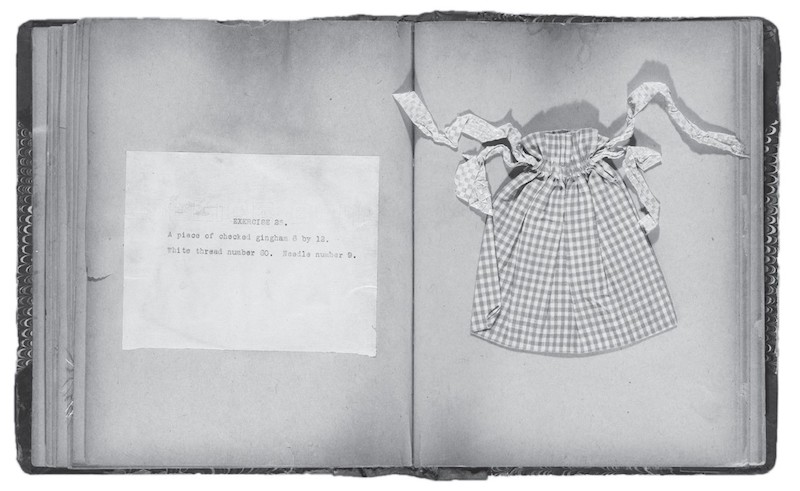

Beatrice Jeanette Whiting’s sewing exercise book, ca. 1915. “Exercise 25: A Piece of Checked Gingham.” Here the young sewer, who would later become a home economics teacher, practiced working a piece of gingham into the form of a small sack. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Beatrice Jeanette Whiting’s sewing exercise book, ca. 1915. “Exercise 25: A Piece of Checked Gingham.” Here the young sewer, who would later become a home economics teacher, practiced working a piece of gingham into the form of a small sack. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

For women in particular, the primary weavers in many (though not all) traditional as well as modern societies, cloth has evoked all of this and more as a manifestation of “female power.” In the basement gallery at the NMAAHC, at the time of this writing, an old cloth sack hangs in a hallway of the unfathomable: scenes and sounds of human sales on American streets. The fabric unfurls in a weighty cascade encased in a chest-high, vertical box beside a boulder once used as an auction block, a video rendition of the poem “The Slave Mother” by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and words stenciled onto the wall listing the monetary value of individuals long dead. This is a portal of horrors, almost too much for the modern-day viewer to bear. Visitors who encounter the sack tend to linger here, perhaps allowing Ruth’s spare words to penetrate their invisible shells.

“Sometimes you have to be quiet with it,” Mary Elliott, co-curator of the slavery exhibition advised as she led me through the buried channel one cold winter day in 2017. “And you may hear voices.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. Used with the permission of the publisher, Random House, a Penguin Random House Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Copyright © 2021 by Tiya Miles.