On March 23, 2010, the day after the House passed Obamacare, Sarah Palin sounded a call to arms—literally.

“Commonsense Conservatives & lovers of America,” she tweeted. “‘Don’t Retreat, Instead—RELOAD!’ Pls see my Facebook page.”

Those visiting her Facebook page found a U.S. map with twenty congressional districts held by Democrats, each marked with rifle crosshairs. She named the twenty Democrats and wrote: “We’ll aim for these races and many others. This is just the first salvo…”

Her thinking was in line with what Sharron Angle, the Republican Senate candidate in Nevada who would face off against Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid in 2010, had said when she floated the idea of taking up arms. “If this Congress keeps going the way it is, people are really looking toward those Second Amendment remedies and saying my goodness what can we do to turn this country around?” she said on a conservative radio show. “I’ll tell you the first thing we need to do is take Harry Reid out.”

She argued that the “Founding Fathers… put that Second Amendment in there for a good reason and that was for the people to protect themselves against a tyrannical government. And in fact Thomas Jefferson said it’s good for a country to have a revolution every 20 years.” That was not “in fact” so, but the endorsement of possible violence was unmistakable.

And Michael Steele, chairman of the Republican National Committee, went on Fox News the same day Palin sounded her call to arms. “Let’s start getting Nancy [Pelosi] ready for the firing line this November,” he proposed.

People heard them, loud and clear. In the days of the House debate and immediately after, violence erupted.

A Tea Party activist, suggesting people “drop by” the home of Representative Tom Perriello, a Virginia Democrat, posted Perriello’s brother’s Charlottesville address online thinking it was the congressman’s—and somebody did indeed “drop by” and cut a gas line.

Bricks shattered the windows and doors of Democratic Party offices in Wichita, Kansas, Cincinnati, Ohio, and Rochester, New York, apparently in response to the call by an Alabama militia leader, Mike Vanderboegh, who posted a message telling “Sons of Liberty” that “if you wish to send a message that Pelosi and her party cannot fail to hear, break their windows. Break them NOW.”

Representative Louise Slaughter, a New York Democrat, was treated to a phone threat mentioning a sniper attack and a brick thrown through the window of her district office.

Representative Bart Stupak, a Michigan Democrat, received a faxed drawing of a noose and a voicemail promising: “You’re dead. We know where you live. We’ll get you.”

Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, the No. 3 Democrat in the House and a senior member of the Congressional Black Caucus, also received a fax with a noose drawing, as well as threats called to his home phone.

Democratic representatives Harry Mitchell of Arizona, Betsy Markey of Colorado, and Steve Driehaus of Ohio received threats of violence, too, and demonstrators besieged Driehaus’s home after foes published his home address online.

Representative Anthony Weiner of New York received a letter containing white powder and a threatening letter. Tea Party demonstrators brought a coffin to the office and home of Democratic representative Russ Carnahan of Missouri.

At least ten House Democrats, in addition to Democratic leaders, had to be assigned protection details. The Senate sergeant-at-arms warned senators to “remain vigilant.”

And, in Tucson, Arizona, somebody shattered the glass door to the office of Democratic Representative Gabrielle Giffords, possibly with a pellet gun.

Just days earlier, House Republican Leader John Boehner had inflamed passions in the House chamber—and far beyond—with his furious cry against Obamacare: “Hell no you can’t!” Others in the House shouted charges of “baby killer” and “tyranny.” Days earlier, Boehner told National Review that if his fellow Ohioan Driehaus voted for Obamacare, “he may be a dead man”—politically speaking, of course.

Now Boehner made a halfhearted attempt to calm the violence—while validating the rage. “I know many Americans are angry over this health-care bill, and that Washington Democrats just aren’t listening,” he said on Fox News. “But, as I’ve said, violence and threats are unacceptable.”

It was a weak effort, and one of the targets, Perriello, said so. “No, the answer is, we want those people to go to jail who are committing a crime,” he told The New York Times. “I think people have to realize what it means to say in a democracy that ‘I will kill your children if you don’t vote a certain way,’” Perriello said. “What’s at stake here is the sanctity of our democracy.”

Slaughter, of New York, went further, accusing Republicans of “fanning the flames with coded rhetoric.”

But the No. 2 House Republican, Eric Cantor, declared the matter “reprehensible”—not the attacks and threats against Demo- crats, but the “reckless” complaints by Democrats such as Slaughter about the violence being visited on them. Such statements “only inflame these situations to dangerous levels.” Cantor justified his blame-the-victim statement by pointing out that somebody had fired a shot at his district office—but it turned out that it was a stray bullet shot into the air; Cantor’s office hadn’t been targeted.

In Tucson, staffers to Gabby Giffords were shaken, not just by having the office door shattered but by a flood of threatening calls and emails. An Arizona Tea Party leader, Trent Humphries, proclaimed that “Giffords is toast.” Even before the Obamacare vote, a suspicious package had been delivered to the Giffords office, and at a “Congress on Your Corner” event at a Tucson supermarket, protesters shouted Giffords down over the health care bill and somebody dropped a gun, which slid across the ground toward Giffords.

Facing the rise of both the Tea Party and the Patriot groups—and increasing overlap between them—Republican officeholders faced a choice: get on board, or get run over.Staffers began to fear for their safety, but Giffords, in an interview with MSNBC’s Chuck Todd and Savannah Guthrie after the shattering of her office door, said she wasn’t afraid. “Our democracy is a beacon to the world because we effect change at the ballot box and not because of these outbursts of violence,” she said, urging both sides to come together and calm the passions. “Look, we can’t stand for this. The rhetoric, and firing people up… We’re on Sarah Palin’s targeted list. The thing is, the way she has it depicted is with the crosshairs of a gunsight over our district. And when people do that, they’ve got to realize there are consequences to that action.”

But Palin pressed on, heedless of the consequences. At a gathering of the Southern Republican Leadership Conference in New Orleans in April, she won hearty applause repeating her new mantra: “Don’t retreat—reload!”

In Arizona, Giffords’s Republican opponent, Jesse Kelly, hosted an event in June that he promoted with a photo of himself in military garb holding an automatic weapon. “Get on Target for Victory in November,” it said. “Help remove Gabrielle Giffords from office. Shoot a fully automatic M16 with Jesse Kelly.”

Giffords squeaked to a victory in November, but she had grown discouraged. On January 7, 2010, she wrote a despairing email to her husband and a friend. “My poor state!” it said. “The nut jobs have stolen it away from the good people of Arizona.”

Three days after her swearing in to a third term, Giffords scheduled another Congress on Your Corner event outside a Tucson Safeway. Her staff had encouraged her to skip it, but Giffords wouldn’t hear of it. She made a robocall to her constituents cheerfully telling them where and when to show up: “This is Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and I hope to meet you in person this Saturday.” When Saturday morning came, she tweeted: “Please stop by to let me know what is on your mind.”

When she arrived, there were more than a dozen people already lined up to talk with her, including a nine-year-old girl, Christina-Taylor Green, who had been elected to her school’s student council and wanted to learn more about government. “Thanks so much for coming,” she told the crowd with a smile.

Near the front of the line, she encountered twenty-two-year-old Jared Loughner, with a shaved head and a crazed look in his eyes. He raised a Glock 19 9mm semiautomatic handgun and, from two feet away, fired a bullet through Giffords’s head.

The gunman continued firing, hitting twenty people in all and killing six of them, including Gabe Zimmerman, a thirty-year-old Giffords staffer, three retirees—and young Christina-Taylor Green, shot in the chest. Also slain was federal judge John Roll, who died heroically shielding Giffords aide Ron Barber. Barber was hit in the cheek and thigh, permanently injuring his leg.

Finally the gunman stopped to reload, and bystanders (including one who had been shot in the head) hit him over the head with a folding chair, wrestled ammunition from him, and knocked him to the ground.

At 2 p.m., National Public Radio erroneously reported that Giffords was dead, and CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC repeated the error. Her husband, NASA astronaut Mark Kelly, broke down in grief when the false report reached him as he rushed home to Arizona on a friend’s jet. (He recounted this and other details in a memoir he later wrote with Giffords.)

Giffords—miraculously—survived the assassin’s bullet. But her life would never be the same. She had been a rising star, and chatter had already begun about a run for higher office. Instead, her brain injury left her with limited use of the right side of her body and aphasia, which makes speech extremely difficult.

The Giffords tragedy has a personal element for me. My wife was her pollster, and I’ve had the privilege of observing Gabby’s heroic struggle to regain her ability to speak. I’ve shared in her joy as her husband (who also hired my wife as his pollster) won election to the Senate—the place where everybody thought Gabby would wind up.

What made this moment different was that, on the airwaves and online, right-wing personalities recklessly fed their audiences paranoid conspiracy theories about the Obama administration that made them fear for their country, and their lives.There’s no evidence that Palin’s violent rhetoric, or anybody else’s, provoked the massacre in Tucson; the killer was obviously deranged, as his political views suggested (he seemed to believe government used grammar to exert mind control). But when the New York Post asked Giffords’s father if his daughter had any enemies, he responded: “Yeah, the whole Tea Party.”

Palin unquestionably deserves blame for one thing: she refused to tone down her rhetoric even after the Tucson massacre. In the days after the shooting, many cited Palin’s violent rhetoric and her crosshairs image over Giffords’s district. Palin called this “a blood libel that serves only to incite… hatred and violence”—a bizarre invocation of the anti-Semitic “blood libel” alleging that Jews consumed the blood of Christian children.

Six months later, she was back to her violent talk. “Now is not the time to retreat,” she told Fox News’s Sean Hannity, “it’s the time to reload.” Eleven months after that, she told a gathering of conservatives in Las Vegas: “Don’t retreat—reload and re-fight.”

Palin and others like her had introduced a new relationship between the Republican Party and political violence. With the rise of the Tea Party, elected officials in the Republican Party chose to fan the antigovernment rage. They tried to ride the tiger, harnessing the energy of the anti-Obama rebellion. In the end, the antigovernment rage wound up consuming the Republicans and turning the GOP into an antigovernment party with an often violent audience.

By historical standards, twenty-first-century political violence hasn’t been particularly lethal. The Equal Justice Initiative has documented 4,384 lynchings by white supremacists between 1877 and 1950. Some 750,000 died in the Civil War. There was Black nationalist, revolutionary leftist, and Puerto Rican nationalist violence in the 1960s and 1970s, and, later, jihadist terrorism.

What made this moment different was that, on the airwaves and online, right-wing personalities recklessly fed their audiences paranoid conspiracy theories about the Obama administration that made them fear for their country, and their lives. With Republican leaders also validating those fears, it became a recipe for rage and, inevitably, violence.

The militia movement of the 1990s, which faded after the Oklahoma City bombing, and was quiet during the Bush presidency, came roaring back. In the first year of Obama’s presidency, the number of antigovernment “Patriot” groups rose to 512 from 149 the year before, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported, with the number of paramilitary groups tripling. By the end of 2012, such Patriot groups had grown to 1,360, SPLC reported.

Then, in 2013 and 2014, something interesting happened: the number of violent groups began to decline. But this wasn’t good news. They had migrated to online organizations such as Stormfront. And, the SPLC reported: “The highly successful infiltration into the political mainstream of many radical-right ideas about Muslims, immigrants, black people and others have stolen much of the fire of the extremists, as more prominent figures co-opt these parts of their program [A] wide variety of hard-right ideas, racial resentments and demonizing conspiracy theories have deeply penetrated the political mainstream, infecting politicians and pundits alike.”

New racist, antigovernment groups sprang up, such as the Oath Keepers (March 2009) and the Three Percenters (late 2008). Registered users of Stormfront murdered close to one hundred people over a five-year period, SPLC found.

Authorities found plots to kill U.S. government officials and attack federal property and mosques. Domestic terrorists went on a spree of lone-wolf attacks on Muslims, police, and government sites. Conspiracy theorists went wild, and not just with the Birther, death panel, and Nazi eugenics lies. Obama planned to impose martial law and socialism and to declare himself president for life. Oklahoma City and 9/11 were false flag operations—inside jobs. The Federal Reserve was facilitating world government and FEMA was building concentration camps. The feds planned door-to-door gun confiscation.

Facing the rise of both the Tea Party and the Patriot groups—and increasing overlap between them—Republican officeholders faced a choice: get on board, or get run over. Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican of South Carolina who voted to confirm Obama nominee Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court, held a town hall meeting in December 2009, at which he was called a “traitor” in a “pact with the devil.”

Responded Graham: “We’re not going to be the party of angry white guys.” But Graham got the message, and became an angry white guy himself.

In the end, the antigovernment rage wound up consuming the Republicans and turning the GOP into an antigovernment party with an often violent audience.Joe Wilson, Republican of South Carolina, debuted the angry-white-guy routine with his infamous “You lie!” shout at Obama on the House floor in September 2009. Boehner tried to persuade Wilson to apologize on the House floor, but Wilson, who said he apologized privately, refused. Boehner excused the Wilson outburst by saying, “Americans are frustrated, they’re angry, and, most importantly, they’re scared to death.”

Now why would that be?

FreedomWorks, a group started by former House Majority Leader Dick Armey, a Texas Republican, tightly affiliated itself with the Tea Party. Representative Tom Price, a Georgia Republican, celebrated the Tea Partiers at one rally by invoking Samuel Adams: “It doesn’t take a majority to prevail, but an irate and tireless minority keen on setting brush fires of freedom in the minds of men. Thank you so much for setting those brush fires.”

Armey himself told the Tea Party faithful their lives were in danger: “Patrick Henry said, ‘Give me liberty or give me death.’ Well, Barack Obama is trying to make good on that.”

The rage of the Tea Party crowd was palpable as they shouted down lawmakers at town hall meetings and carried posters with menacing messages: threats to stop Obamacare with “a Browning”—a gun; an image of an assault rifle with the message “Come and Take It”; and, everywhere, Thomas Jefferson’s saying: “The Tree of Liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.”

At one rally across the Potomac River from Washington in Virginia, a group of armed demonstrators, carrying AK-47s and pistols, observed the fifteenth anniversary of the Oklahoma City bombing. They were led by Mike Vanderboegh, the man who had called for bricks to be thrown through windows of Democratic Party offices. He told his armed followers that Democrats “are pushing this country toward civil war and they should stop before somebody gets hurt.” He suggested they might have reached the point where they would be “absolved from any further obedience” to the government.

Cravenly, Republicans opened the doors to the Capitol and welcomed such sentiments—and the people voicing them.

On the weekend in March 2010 when the House neared final passage of Obamacare, Tea Party demonstrators besieged the Capitol. The mob got to within fifty feet of the Capitol, and Democrats worried aloud about the possibility of violence. Police struggled to hold back the crowd. But many Republican lawmakers chose to whip the protesters into a frenzy.

GOP officials—including the head of the House Republicans’ 2010 campaign committee—went out onto the balcony, waved handwritten signs, and led the crowd in chants of “Kill the bill.” A few waved the yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” flag appropriated by the Tea Party movement. Inside the chamber, they howled out of control: “Baby killer!” “Say no to totalitarianism!”

“That’s kind of fun,” Representative Mary Fallin of Oklahoma said cheerfully after riling the crowd with a sign saying “NO” in red letters.

Representative Barney Frank of Massachusetts, an openly gay Democrat who had been called “faggot” and “homo” by the mob, accurately observed that some Republicans “think they are benefitting from this rancor.”

___________________________________

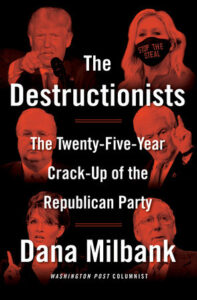

Excerpted from The Destructionists: The Twenty-Five-Year Crack-Up of the Republican Party by Dana Milbank. Copyright © 2022. Available from Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.