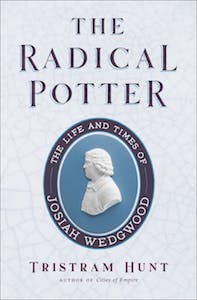

How the Potter Josiah Wedgwood Created an Iconic Abolitionist Medallion

Tristram Hunt on the Union of Moral Passion and Commercial Acumen

As a patriot, Nonconformist, internationalist and political reformer, Josiah Wedgwood was instantly sympathetic towards the growing calls for abolition. There were a couple of lines from William Cowper’s poem which might have made him reflect: “Think how many backs have smarted / For the sweets your cane affords.” For not only did Wedgwood and his Staffordshire peers export large quantities of pottery to the plantation estates and booming Caribbean cities of Bridgetown and Kingston, and supply the slaving merchants of Bristol and Liverpool with their creamware punchbowls, Wedgwood himself had even taken a specific commission from a slave trader who ordered a “nest of baths . . . to please the fancy of a black king of Africa to wash himself out of.”

So much of Georgian Britain’s economic prosperity was inextricably linked to the Triangular Trade. This interpretation was first developed in Eric Williams’s Capitalism and Slavery (1944), which traced the way profits from the Atlantic slave trade “fertilized the entire productive system” of Great Britain. The Welsh slate industry, Manchester textile production, Glaswegian, Bristol and Liverpool banking, shipbuilding and even ceramics were all buoyed by funds drawn from the plantation system. “It was the capital accumulation from the West Indies trade that financed James Watt and the steam engine,” wrote Williams. More recent scholarship has confirmed just how closely profits in the colonies from advanced sugar production, as well as captive markets, assisted the industrialization process.

Profits derived from the sugar and slave nexus could have furnished anything from 20 to 55 per cent of Britain’s gross fixed capital formation in 1770, crucially underpinning the UK economy as a whole and easing financial or credit problems in technically advanced sectors. Investment not only in new technologies, but also in the infrastructure of ports, new docks (most notably in London and Liverpool), canals, turnpikes and new manufactories which were made possible by the wealth pouring in from the West Indies.

Slavery was also a part of the consumer economy through its provision of sugar and cocoa, molasses and cotton. Wedgwood’s pottery production benefited enormously from this middle-class luxury market as well as depending on the network of aristocratic families whose fortunes were made, or bolstered by, plantation profits. In 1778, the former Prime Minister Lord Shelburne suggested that “there were scarcely ten miles together throughout the country where the house and estate of a rich West Indian was not to be seen.” From Kedleston Hall to Stourhead, the very houses which proclaimed the historic liberty of Englishmen and Britain’s blessed role in the story of freedom were often endowed and decorated with riches acquired from human trafficking. At the time, there was very little public commentary about the bloodied origins of so much new aristocratic wealth.

Indeed, when Wedgwood celebrated his vision of Britain in the Frog Service one of the most spectacular pieces was a towering glacier for the dessert service emblazoned with an image of Harewood House—the neo-classical Yorkshire seat of the Lascelles family, whose money came from their 27,000 acres of sugar-cane fields in Barbados, Jamaica, Grenada and Tobago, and from the particularly inhumane fleet of slaving vessels which trafficked slaves across the Atlantic to the Guinea coast at Anomabu.

By the mid-1780s, despite the unacknowledged position of his business within the nexus of slavery, Wedgwood became utterly convinced of the immorality of the trade. In 1783 the Quakers presented the first anti-slavery petition to Parliament, and in the same year the abolitionist campaigner Granville Sharp used the grotesque case of the Zong—in which Captain Luke Collingwood sought to claim insurance on the 133 enslaved Africans he threw overboard during the Middle Passage as he supposedly ran low on drinking water—to agitate in favor of abolition. In May 1787, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, or London Committee, was established by William Wilberforce alongside Sharp and the reformer Thomas Clarkson, whose Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1786) was a key text in the battle against human bondage.

From Kedleston Hall to Stourhead, the very houses which proclaimed the historic liberty of Englishmen and Britain’s blessed role in the story of freedom were often endowed and decorated with riches acquired from human trafficking.

The London Committee was conceived as a means “for procuring such Information and Evidence, and for distributing Clarkson’s Essay and such other Publications, as may tend to the Abolition of the Slave Trade.” It was also the vehicle for Clarkson’s hugely innovative program of activism—petitions, boycotts, open meetings, parliamentary lobbying and community organizing across the country—to drum up public support for abolition. Together with his political hero Major John Cartwright, Wedgwood was elected on to the Committee. From the start, he took his responsibilities seriously, attending seven meetings in 1788 and then at least one in every succeeding year.

In 1791, his son Joss joined him on the Committee while his Lunar Society circle of Matthew Boulton, Joseph Priestley, Samuel Galton and Erasmus Darwin all lent their support. “I have just heard that there are muzzles or gags made at Birmingham for the slaves in our islands. If this be true, and such an instrument could be exhibited by a speaker in the house of commons, it might have a great effect,” Darwin suggested to Wedgwood in April 1789.

We have the clearest insight into Wedgwood’s ethical stance and his attempts to shape public opinion about slavery in a long letter he wrote in February 1788 to Anna Seward—the poet, frustrated paramour of Erasmus Darwin and so-called Swan of Lichfield. Knowing her ambivalent sentiments on the subject, Wedgwood addressed objections to abolition—“that we should sacrifice our West India commerce, and that the slaves would only change their masters, without being able to shake off their bondage”—before explaining “what has come to my knowledge of the accumulated distress brought upon millions of our fellow creatures by this inhuman traffic.”

In practical terms, he thought that plantation profits—from which many powerful families around Lichfield and South Staffordshire gained mightily—would be retained under a system of free labour, more extensive mechanization (as at Etruria) and productive levels of investment. Yet ultimately, for Wedgwood the rational Dissenter and enthusiast for the American and French revolutions, the case for abolition was one of equality and a belief in the “rights of man” rather than based on any commercial calculus. “And even if our commerce was likely to suffer from the abolition, I persuade myself that when this traffic comes to be discussed and fully known, there will be but few advocates for the continuance of it.”

While he was perennially disappointed by the reactionary apathy of his Staffordshire neighbors—“in this county I know of no subscribers & I fear the gentlemen . . . have not paid much attention to the subject”—Wedgwood continued to believe that “the people will shew clearly that they interest themselves in this cause and will not be satisfied whilst the national character is stigmatized by injustice and murder.” As a sign of his personal commitment, he determined to support the most eloquent and effective campaigner for abolition, Olaudah Equiano, or “Gustavus Vassa, The African,” whose account of the Middle Passage and sale into bondage in Barbados (“The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable”), provided a devastating indictment of the barbarity of slavery.

In Wedgwood’s own copy of Equiano’s autobiography—The Interesting Narrative (1789—there is a personal message from the author to Josiah: “I pray you to pardon this freedom that I have taken in begging your favour in the appearance of your name amongst others of my worthy friends.” Such was their friendship that when Equiano bravely agreed to travel to the slaving hub of Bristol for a public reading, he asked Wedgwood to help ensure his safety.

I mean next Week to be in Bristol where I have some of my narrative engaged—& I am very apt to think I must have enemys there—on the amount of my Publick spirit to put an end to the accursed practice of Slavery—or rather in being active to have the Slave Trade Abolished. Dear Sir I leave London on Friday the 23rd instantly therefore will take it a particular favour if you will be kind enough as to Direct to me few Lines at the post office— till Called fo—Bristol.

Wedgwood replied that he hoped Equiano would not be in any danger, “but if it should be otherwise you may direct a letter to Mr Byerley, No 5 Greek Street, Soho, acquainting him with your situation and he will take the necessary steps with Mr Stevens of the British Admiralty in your favour.” Over many years, Wedgwood wrote impassioned letters, circulated petitions, attended meetings and joined boycotts. He also purchased shares in Clarkson’s Sierra Leone Company, established in 1791 as an evangelical colony in West Africa for freed slaves specifically designed to disrupt the Atlantic trade. “The first company ever instituted for the abolition of the slave trade, the cultivation of Africa, and the introduction of the Gospel there.” However, his most important contribution was to unite this moral passion with his manufacturing and commercial acumen.

His most important contribution to abolition was to unite this moral passion with his manufacturing and commercial acumen.

In Darwin’s The Botanic Garden, two lines stand out which visualize the thinking of Wedgwood and his fellow abolitionists: “poor fetter’d SLAVE on bended knee / From Britain’s sons imploring to be free.” Ever since the Plymouth Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade published their infamous engraving Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck with Negroes in Proportion of Only One to a Ton, depicting the hideous, cramped and arithmetically calculated confinement of enslaved Africans aboard the Liverpool slaver Brookes, Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson knew that striking imagery was key in the propaganda war. The Plan was rapidly reprinted by the London Committee with editions circulating across the country, highlighting the inhumanity of the Atlantic trade. It also had the unintended effect of codifying the position of the slave as one of uniform passivity and victimhood. Wedgwood combined that interpretation with Darwin’s pleading image in the production of what became an iconic medallion.

Sculpted by Henry Webber and then modeled at Etruria by William Hackwood from the Committee’s original motif (which had previously appeared only in print), the oval white jasperware medallion has the black relief of a chained male slave in a half-kneeling posture facing right with the inscription “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” Clarkson described the design’s appearance before the London Committee in his History of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1808):

On the second and sixteenth of October [1787] two sittings took place; at the latter of which a sub-committee, which had been appointed for the purpose, brought in a design for a seal. An African was seen, in chains in a supplicating posture, kneeling with one knee upon the ground, and with both his hands lifted up to Heaven, and round the seal was observed the following motto, as if he was uttering the words himself—“Am I not a Man and a Brother?” The design having been approved of, a seal was ordered to be engraved from it. I may mention here, that this seal, simple as the design was, was made to contribute largely . . . towards turning the attention of our countrymen to the case of the injured Africans, and of procuring a warm interest in their favour.

The image of the slave was entirely generic. The black relief depicted what were regarded as characteristically African features which served to depersonalize him in a similar manner to the depiction of cargo in the Brookes. As Clarkson put it, “the Negro, who was seen imploring compassion, was in his own native colours.” The bended knee, heavy chains, pleading hands and appeal to mercy all positioned the slave as helpless, unthreatening and submissive. The image was designed to spark both guilt and pity. Thus for the abolitionist movement the favored mode of liberation would not be by popular resistance on the plantations of Barbados or armed rebellion during the Middle Passage, but by high-minded petitions, consumer boycotts, prayer days, parliamentary bills and the humanitarian impulses of England’s white, middling sort.

Power remained with the civilized, Christian Britons and the liberation of enslaved Africans would be appropriated as another chapter in England’s glorious progress of ever advancing liberty. Even though the consumer revolution of the eighteenth century had helped to fuel the Atlantic slave trade, Wedgwood’s understanding of its ethos of emulation now enabled him to popularize abolitionism more effectively than any number of Sharp petitions or Equiano readings.

_____________________________________________________________

Excerpted from THE RADICAL POTTER: The Life and Times of Josiah Wedgwood by Tristram Hunt. Published by Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2021 by Tristram Hunt. All rights reserved.

Tristram Hunt

Tristram Hunt is the director of the Victoria & Albert Museum and one of Britain’s best-known historians. His previous books, which include Cities of Empire: The British Colonies and the Creation of the Urban World and Marx’s General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels, have been published in more than a dozen languages. Until taking on the leadership of the V&A, he served as Member of Parliament for Stoke-on-Trent, the home of Wedgwood’s potteries. A senior lecturer in British history at Queen Mary University of London, he appears regularly on BBC radio and television.