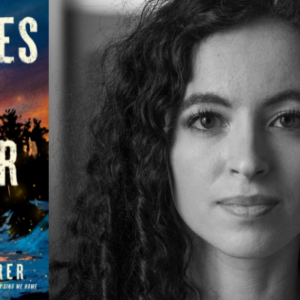

How the Lessons of “Lady Doctors” of the 19th Century Helped Write a Contemporary Novel

Ritu Mukerji on the Life of Ann Preston and the Enduring Power of Medical Fiction

“Work where the work opens.”*

This was a favored phrase of Dr. Ann Preston, a physician and professor at one of the first medical schools for women, and one she often told her students.

I was doing research for my novel, a medical mystery set in 19th century Philadelphia, at Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. I would often be moved by an old photograph, a painting, or a fragment of a diary entry. The bulletin board above my desk was loaded with postcards and scraps of paper with quotes, the visual inspiration that sparked my imagination.

“Work where the work opens.” I wrote it down on a Post-It note and placed it on my computer monitor. The words became a guide for me.

Becoming an author was a daunting prospect and I was hardly an ideal candidate. I had no background in a writing career and little qualification other than being an avid reader, with a love of mystery and crime fiction. I had long dreamed of writing a mystery novel but only started writing when I was in my mid-forties, while working as a doctor.

I had lived in Philadelphia as a medical student, walking the same cobblestone streets as my characters. Yet I knew little about the history of unique institution that was “Woman’s Med.” I was fascinated to learn of Dr. Caroline Still Anderson, one of the first Black women physicians in the US and an 1878 graduate of the college. Or Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi, scientist and professor, the first woman to become a member of the Academy of Medicine. I often looked at a striking studio portrait of three international students, Dr. Anandibai Joshi, Dr Keiko Okami and Dr. Sabat Islambouli, who returned to their home countries to practice medicine.

I had lived in Philadelphia as a medical student, walking the same cobblestone streets as my characters. Yet I knew little about the history of unique institution that was “Woman’s Med.”

But it was Dr. Preston’s straightforward phrase, from a diary entry in October 1861, that resonated deeply with me.

Dr. Preston was a Quaker, an abolitionist and pro-temperance activist. She had been a schoolteacher and a children’s book author before entering medical school at 38. She would later become dean of the college, a vocal advocate for women’s medical education.

But the moment in 1861 was one of devastating setback, as the personal and professional collided for her. The country was on the precipice of a long and terrible war. Due to limited funds and lack of enrollment, the medical school’s board of corporators voted to suspend the 1861-2 session. The college would close its doors.

Dr. Preston wrote:

I have been sad for my country, because it is slow to learn the wisdom which would bring prosperity…sad in the prospects of the Institution to which I have given so much of my time and strength, for there now seems no possibility of success; and I fear that, after all these years of toil, we may be doomed to succumb to the weight of opposition.

But then she offers this: “Tonight the inward encouragement is do thy best; work where the work opens, applauded or condemned, speak and write thy grandest inspiration, thy noblest idea…for thy work has been no failure.”

The words were old-fashioned, weighty with religious overtones. But I was so moved by the courage she draws upon, the call to face an uncertain future and keep going, to focus on the things that you can control.

“Work where the work opens.” There was something fluid and expansive about the phrase, its meaning open-ended. And I took the words to heart: there would never be an ideal time to start writing the novel. There was only now.

My routine developed simply. I sat at the kitchen table, writing in the early morning before going to work, or late at night, after my three kids were asleep. My initial efforts were full of starts and stops. There were many days when I felt so overwhelmed and I would put the work away, frustrated by my lack of progress.

But I kept going, and a stubborn resilience emerged. My years of medical training had given me skills that were well-suited to a writer’s life. I knew how to pivot from a challenge and to start again. I knew how to set a far-off goal and work towards it slowly, to not get discouraged easily. The long hours of reading and research were a natural extension of what I already loved to do.

And I was captivated by the lives of these pioneering doctors. There were schoolteachers, missionaries who lived and worked abroad, journalists and writers, temperance activists. Some were the product of progressive families with an activist bent, encouraged in their studies. Others had to forge their own path, funding their medical education by working other jobs. And in the midst of serious work, there was the joy of living. I was delighted by an old photograph of students dressed in full costume for Halloween. That single image inspired one of my favorite scenes in the book.

I understood firsthand the rigors of medical training, and marveled at what they had done. And though our lives were separated by more than a century, their words felt modern and relevant: the need to feel valued for their life’s work, to have the same opportunities as their male colleagues.

Many were wives and mothers, and this had resonance for me, as my oldest son was born during my second year of residency. Those days are seared into memory: I remember being pregnant, while working on call in the hospital and caring for patients. Or of being a new mother and toting my breast pump into work. I would slip into a call room or the nurses’ station, using moments on a break to pump. Or years later, studying for national board certification exam, while working full time with three young children at home. The tenuous balance of the professional and personal was woven through my career.

So the lessons from the “lady doctors” helped me write the book: a willingness to be bold and not be limited by circumstances, to try and fail, and to free myself from the outcome.

So the lessons from the “lady doctors” helped me write the book: a willingness to be bold and not be limited by circumstances, to try and fail, and to free myself from the outcome. And over time, the writing became a place of creative renewal. Even on the most difficult days, it never felt like an obligation. It was an expansive space, not a constricting one.

And this was never truer than during the pandemic. I would spend long days working and caring for patients, uncertainty and anxiety closing in around me. My three children were at home doing remote schooling. And it was then that the writing became a lifeline—I looked forward to the pleasure and freedom of that space, my imagination unfettered. Even when I felt tired, I would edit a paragraph, or read a few passages of poetry, or delve into an article on early autopsy science. Even a small step would keep the momentum flowing.

“Work where the work opens.” And so it was not in the grand gesture, but in the consistent small steps that the book was written. The post-It note with Dr. Preston’s phrase has curled with age, the ink faded. But the words still ring true. You never know the surprising and fulfilling places it may take you.

* Note: Dr. Ann Preston, diary excerpt, October 1861; from Peitzman, Steven J., A New and Untried Course, p.21-22; Rutgers University Press, 2000.

______________________________

Murder by Degrees by Ritu Mukerji is available via Simon & Schuster.

Ritu Mukerji

Ritu Mukerji was born in Kolkata, India, and raised in the San Francisco Bay area. From a young age, she has been an avid reader of mysteries, from Golden Age crime fiction to police procedurals and the novels of P.D. James and Ruth Rendell. She received a BA in history from Columbia University and a medical degree from Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. She completed residency training at the University of California, Davis and has been a practicing internist for fifteen years. She lives in Marin County, California, with her husband and three children. She is the author of Murder by Degrees.