How the Labor of Enslaved Black Men Built the White House

Corey Mead on the Construction of America's New Capital City

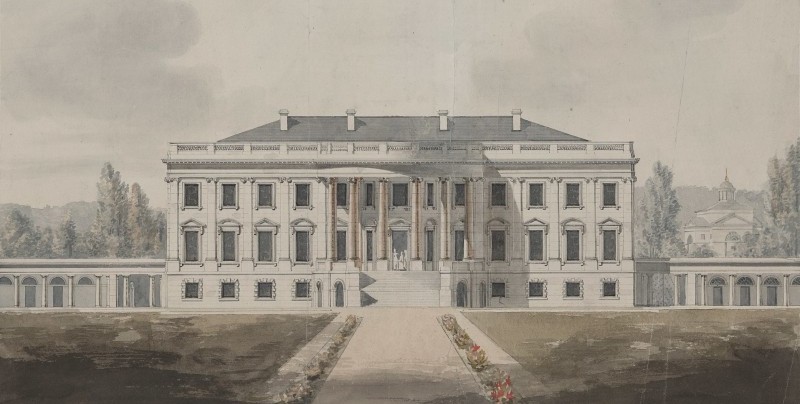

George Washington arrived in Georgetown on July 16, 1792, to judge the final entries in the competition for who would build “The President’s House.” The next morning, a young Irish builder named James Hoban was announced the winner. His drawing showed a three-story rectangular building of dressed stone with a frontispiece of engaged columns. (At Washington’s direction, he later added stone embellishments and enlarged the building’s scale.) Rather than the $500 prize money, Hoban opted for a medal of similar value. The wisely political move—honor over money—impressed Washington and the commissioners all the more. The savvy Hoban soon informed the newspapers back in Charleston of his triumph.

Washington journeyed back to Mount Vernon for a summer holiday while the commissioners drew up business arrangements with Hoban, who was to be paid a healthy salary. Hoban’s contract also stipulated that he was free to work on any construction projects the commissioners desired, not just the President’s House. Because none of the commissioners had any direct building experience, hiring Hoban as a full-time representative made perfect sense, and it added a needed element of security to the enormous task ahead.

In keeping with slavery’s cruel economics, the men would not keep a penny of their earnings.

On the morning of July 19, the commissioners accompanied Hoban to the site of the President’s House to watch him stake out the new foundation. Hoban’s plan for a rectangular house raised questions, however: Should the building be centered directly on the Pennsylvania Avenue axis to the planned Capitol? Should it be set to the front or back of the plot? The commissioners wrote to Washington for advice.

Washington, an experienced surveyor, was delighted to help. On August 2, he met with Hoban and the commissioners at the building site. Washington walked the grounds, making calculations. According to the commissioners, the issue gave the president “considerable Trouble and difficulty to fix his mind.” At last he decided the house should remain where L’Enfant had originally planned, which meant it would not be framed by Pennsylvania Avenue. The commissioners were dismayed but remained silent, as they had wanted a direct vista between the President’s House and the Capitol.

On October 13, 1792, a group of men gathered at the Fountain Inn for a groundbreaking ceremony. Making their way beneath canopies of leaves turning from green to yellow and red, the group walked in parade formation along the dirt road from Georgetown to the building site. Wielding ceremonial truncheons and wands, a contingent of Freemasons—the popular fraternal organization of which Washington was a member—marched in front. The Masons were outfitted in full regalia of satin aprons, badges, and sashes. They were followed by Washington’s three commissioners and “Gentlemen of the town and neighborhood.” Laborers and craftsmen brought up the rear.

Once at the building site, the Freemasons brandished symbolic offerings of corn, wine, and oil, representing a Masonic belief in nourishment, refreshment, and joy and, on a higher plane, science, virtue, and the Brotherhood itself. One Mason cradled the Bible on a satin cushion. Another gave a rousing speech venerating President Washington and his nascent federal city. The ceremony concluded with the placing of an inscribed stone at the site’s southwest corner: “This first stone of the President’s House was laid the 13th day of October 1792, and in the seventeenth year of the independence of the United States of America.” Construction on the President’s House had officially begun.

Ceremony aside, labor on the President’s House had actually started one year earlier, when Pierre L’Enfant had hired approximately 150 enslaved Black men to “throw up Clay” for the building’s foundation. Leased from their owners by the month, these men performed the arduous labor of removing earth from the cellars until January’s winter freeze halted their work.

The commissioners were pleased by the results, and in March they decided they would continue to employ “good laboring negroes by the year, their masters clothing them well and finding each a blanket.” The commission itself would provide two meals a day of cornmeal and pork or beef and basic medical care. Small, unpainted wooden huts, lined up twenty feet apart, would be constructed to house the men. The salary for the enslaved laborers was healthy: twenty-one pounds per year. But in keeping with slavery’s cruel economics, the men would not keep a penny of their earnings. All the money would go instead to their owners. If an enslaved worker failed to show, the overseer simply docked the owner’s pay.

Though exact numbers are impossible to know, more than two hundred documented enslaved men, and likely many more, labored on the President’s House and the larger federal city project. James Hoban himself brought four of his enslaved workers—Peter, Ben, Harry, and Daniel—from Charleston to work on the President’s House. Despite how grueling and essential their labor was, virtually nothing is known about these hundreds of men beyond their first names. The lives of enslaved laborers simply weren’t considered worth documenting at the time. On payrolls and timesheets, their presence is generally denoted as the enslaved individual’s first name, their owner’s last or full name, and their owner’s signature. For example, one timesheet for the project contains the name “N Jacob George Fenwick.” N indicates the worker was enslaved. His first name was Jacob, and his owner was named George Fenwick.

Despite how grueling and essential their labor was, virtually nothing is known about these hundreds of men beyond their first names.

In April 1792, the enslaved laborers, joined by white wage workers and indentured servants, began clearing trees and stumps from the federal city’s planned streets. Yard by yard they hacked broad avenues through verdant forests of oak, using the downed lumber to build bridges and wharves. Expanding outward from the site of the President’s House, the men stripped fences and fence-row trees from areas marked by stakes. They removed dead animals and lugged heavy stones. The brutal labor of clearing the land lasted from daybreak to dark, often seven days a week.

The project’s first workshop was built later that spring in the middle of what is today Lafayette Square. Fifty feet long and twenty-four feet wide, the plank-roofed structure was raised on piers and featured large double doors at one end. Workers dubbed it the “carpenters’ hall.” Soon the workshop was filled with axes, wedges, sledgehammers, and mattocks crafted by a Georgetown blacksmith. By summer’s end, with Hoban now leading the project, enslaved men began laying the foundation for the President’s House. Thick beds of rubble were placed over layers of clay. Foundation stones followed. Cut-stone blocks marked the basement, followed by walls. Washington and Jefferson were thrilled by the progress.

By October, a great deal of land had been cleared. The project’s next phase required hundreds of skilled craftsmen, in part because Washington was adamant that the President’s House and other federal buildings have stone walls. In addition to stonemasons, the project required carpenters, joiners, and brickmakers, among other specialists. The commissioners had naively assumed that craftsmen by the hordes would be attracted by a building project as massive as the federal city. The hard truth, as Jefferson warned, was that the nation’s available craftsmen had more than enough work in such flourishing cities as Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Baltimore, and Charleston. Most had little interest in leaving behind the comforts and resources of those cities for a stripped building site containing a smattering of houses on the banks of the Potomac.

Initially the commissioners had planned on using enslaved labor for the sole purpose of digging foundations and clearing the land. But after witnessing the high-quality work the enslaved Black workers performed, the commissioners decided to greatly expand the variety of jobs assigned to them. Economics also played a role in this change in policy: Slave labor was a sustainable and cost-effective means of meeting the demand for workers. By 1793, a number of local slaveholders were profiting from the demand by hiring out their slaves. For example, slaveholder Edmund Plowden hired out Gerald, Tony, and Jack. Slaveholding sisters Elizabeth, Eleanor, Jane, Mary, and Teresa Brent hired out Charles, Davy, Gabriel, Henry, and Nance. Slaveholder Joseph Queen hired out Gerald, Tony, and Jack.

Before long, the city and surrounding areas were populated by so many Blacks, both enslaved and free, that Georgetown passed laws forbidding slaves and indentured servants from gathering in groups of larger than five, for fear that such assemblies could lead to rebellion. Punishment included thirty-nine lashes for the slave and a fine for the slaveholder.

__________________________________

From The Hidden History of the White House: Power Struggles, Scandals, and Defining Moments by Corey Mead. Forward by Kate Andersen Brower. Copyright © 2024. Available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Corey Mead

Corey Mead is an associate professor of English at Baruch College, City University of New York. He is the author of three books, including Angelic Music: The Story of Benjamin Franklin’s Glass Armonica. His work has appeared in Time, Salon, The Daily Beast, and numerous literary journals.