Harry Smith grudgingly realized that Lionel Ziprin might be right: there was only so long that he could get by sleeping on people’s sofas, cadging meals, and stashing his records, books, films, and paintings wherever he could. The records he shipped from California were his only liquid asset, something he was sure he could sell, but selling them was a slow process, and he hated the idea of his most prized records being scattered among collectors who would hoard them for themselves. He had justified his own collecting as creating a carefully curated selection of the best of American folk recordings, which he hoped would one day be placed in a library or museum, but who would pay for that?

Pete Kaufman suggested that he might be able to sell them in bulk to Folkways Records, a small new company at the center of what was becoming a folk music revival that was beginning to reissue old recordings. Harry had no idea that his records had any monetary value beyond a few collectors, though he thought that if they could somehow reach a larger audience, they might alter the way people thought about music. He was fond of quoting Plato on music having the power to change society.

The owner of Folkways was Moses Asch, a pioneer in boutique recordings of jazz and folk artists with his Disc and Asch record labels, and now with his new Folkways project he was on a mission to record, issue, and reissue seemingly everything—Pete Seeger, Dave Van Ronk, and other folk singers, but also poetry readings, the sounds of junkyards, instructions on how to learn Morse code, cantorial chants, the drumming and singing of boys’ gangs, political speeches, and avant-garde, ethnic, and old-time music. Knowing there was no way for him to compete with the established recording companies, Asch’s plan was to do what they wouldn’t: record what they didn’t record, aim at sales to libraries and schools, and keep everything available from sale forever. It was this openness to all forms of music and his promise to keep all the records in his catalog that quickly gained him respect among musicians and singers.

These songs were evidence of ways of living and performing not found in history books.Moe Asch was the son of Sholem Asch, then the leading Yiddish novelist and playwright. Though Moe was born in Poland and had lived in Paris, studied engineering in Berlin, and grown up among theater people and Jewish intellectuals (it was Albert Einstein who encouraged him to record folk music), Asch said he had never met anyone like Harry—the closest was Woody Guthrie, that self-made, organic intellectual who arrived in New York disguised as a hick. “Woody would come to the studio or fall down on the floor…wild hair and everything…and pull off jokes…Get him in front of a microphone he’d croon and he’d cry…but his presentation was formal. You knew that the man had a statement to make and he made it.”

Moe was one of the few people in New York who knew something of the full range of Harry’s work in the arts, yet even he was astonished to find out how large Smith’s collection of commercially recorded country, blues, and religious records was, and how much he knew about them. “He understood the content of the records. He knew their relationship to folk music, their relationship to English literature, and their relationship to the world,” he said.

Harry offered to sell some of his collection to Folkways when Asch began putting together a five-volume set titled Music of the World’s Peoples, selected by the composer Henry Cowell, and an eleven-volume set of long-playing 33 1/3-rpm records on the history of jazz made up of older, hard-to-find 78-rpm records selected by Frederic Ramsey, Asch, and Harry. The new long-playing format seemed perfect for anthologies. For the first time it was possible to listen to one song after another without changing the record or turning it over. Six or seven pieces of music could be put on each side of an LP, and the music could be sequenced creatively. Moe bought some of Harry’s 78-rpm records for anywhere from 35 cents to $2 each, and used a few of them as part of several of his reissue projects. “I began selling off Bukka White, Champion Jack Dupree, and other stuff that I considered to be of a sort of second rate,” Harry said, “and anyhow easily replaceable. [Asch] was astounded by the stuff!” Moe then proposed that they both could make more money if Harry put together a collection of these old records for reissue, something the big recording companies were slow to do. The idea of treating it as an anthology with extensive notes on the performers and the background of the music was Harry’s idea, and it made the record sets appear as serious as books. If Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren’s widely used 1938 textbook Understanding Poetry: An Anthology for College Students could contain the texts of songs like “The Daemon Lover” or “Frankie and Johnnie” and declare them literature, then Harry could include commercial recordings of the same songs in his record anthology and claim their equal importance.

On May 15, 1952, Harry signed an agreement with Folkways Records for a $200 advance ($1,900 today) with royalties of 20 cents ($1.87) per record sold. They also agreed that Asch could create new albums by using any recordings Harry had, but Harry would be allowed to sell them to collectors before Folkways reissued them.

Moe was excited by the idea despite some initial doubts about Harry’s reliability, but he found him easy to work with, and often pointed to his anthology as an example of how record reissues should be done:

Harry Smith is an authority. He not only is the collector, he knows the record, he knows what he wants to say in what form he wants to do it and he has a concept of the complete package. He comes to me and we discuss it. And I say, “Harry, I love it. You just give me the finished manuscripts and give me the form that you want it and I’ll issue it exactly the way you want it.”…Everything is Harry Smith.

Asch told the folk music collector and musician Ralph Rinzler that he had provided Harry with a room in which to work, a typewriter, the books he needed, and every so often he’d give him a button of peyote. Rinzer doubted that Asch was serious about the drug, but admitted that there was a “dreamlike, visionary quality” to Harry’s album notes.

The transfer of the 78-rpm records to the 33 1/3-rpm long-playing format was done by Peter Bartók, who was familiar with folk music and the problems of recording it, having already remastered the field recordings of his father, the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, for Folkways.

In 1952, The Anthology of American Folk Music was released, a set of six LP records divided into three sets of two LPs, titled “Ballads,” “Social Music” (both sacred and secular), and “Songs,” each accompanied by an elaborately conceived booklet of notes. The music was a selection of white country music (“hillbilly”) and African American (“race”) records that were made between 1927, when, Harry said, “electronic recording made possible accurate music reproduction, and 1932, when the Depression halted folk music sales. During this five-year period, American music still retained some of the regional qualities evident in the days before phonograph, radio, and talking pictures had tended to integrate local types.” Harry’s record notes indicated that he had plans to do three more sets of records and that they would be “devoted to examples of rhythm changes between 1890 and 1950.”

The models for this project were several compilations of previously issued commercial folk recordings that Alan Lomax produced in the 1940s: Smoky Mountain Ballads for RCA in 1941, and Mountain Frolic and Listen to Our Story—A Panorama of American Balladry for Brunswick Records, both of which first appeared in 1947 as 78-rpm recordings and were later reissued in 1950 among the first recordings produced on long-playing records. Another of Harry’s sources was Lomax’s “List of American Folk Songs on Commercial Records” that was put together in 1940 for the Library of Congress and made available to the public. After listening to some 3,000 recordings, Lomax had chosen 350 as especially important, and 60 of these as the best. Twelve of those 60 were included in Harry’s Anthology, and many of the others were by performers who were also on Lomax’s list. Smith urged other collectors he knew to write to the Library of Congress for a copy of the list.

Because Harry was unknown to most folk music enthusiasts, many assumed that the Anthology had been compiled by Lomax under a pseudonym to avoid legal problems. But Lomax’s self-exile to Europe in the face of a congressional hunt for leftist folklorists and singers rendered his work largely forgotten by the public.

Smith said he had chosen the records for the Anthology not because they were the best he could find, but rather because they were “odd,” or “exotic in relation to what was considered to be the world culture of high-class music.” They were “selected to be ones that would be popular among musicologists or possibly with people who would want to sing them and maybe would improve the version.”

Intuition is employed in determining in what category, information can be got out of. I intuitively decided I wanted to collect records. After that had been determined, what was then decided to be good or bad was based on a comparison of that record to other records. Or the perfection of the performance. To a great degree, it seems like a conditioned reflex. What is considered good? Practically anything can be good. Consciousness can only take in so much. You can only think of something as so good. When you get up among, say, top musicians or top painters—which one is the best? Either things are enjoyable or they are unenjoyable. I determined what the norms were. You can tell if you hear a few fiddle records, when one is the most removed [exceptional] violin playing of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. If that seemed to be consistent within itself, that would be the good record; if it was a good performance of what it was. Now, it was merely my interest in looking for exotic music. The things that were most exotic—whether it happened to be the words or melodies or timbre of the instruments—that really was what selected those things.

Yet he also said that some of them, like “Brilliancy Medley,” by Eck Robertson, were picked simply because he liked them or because they were important versions of a well-known song. His criteria for choosing commercial recordings were not far from what Lomax said was behind his selections for his Library of Congress list:

The choices have been personal and have been made for all sorts of reasons. Some of the records are interesting for their complete authenticity of performance; some for the melodies; some because they included texts of important or representative songs; some because they represented typical contemporary deviations from rural singing and playing styles of fifty years ago; some to make the list as nearly as possible typical of the material examined.

The order in which Smith placed the records was apparently carefully thought out. His categories of “Ballads,” “Social Music,” and “Songs” follow the groupings of songs from Francis James Child’s English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Cecil Sharp’s English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, and Lomax’s songbooks. “Henry Lee” by Dick Justice was the first track on the “Ballad” set of records because it was the lowest number of the five ballads in his set that were also in Child’s classic collection of ballads in the English language. But his reasoning was not always obvious, most notably with “The Moonshiner’s Dance, Part 1” by Frank Cloutier and the Victoria Café Orchestra, a medley of songs, most of which would never be called a folk song: “When You and I Were Young, Maggie,” “How Dry I Am,” “Turkey in the Straw,” “At the Cross,” “Jenny Lind Polka,” and “When You Wore a Tulip.” This was the only recording from the Northern states in the Anthology, and it appears to be part of a stage review set in the Victoria Café in St. Paul, Minnesota, with a list of vaudevillian jokes and Prohibition humor tossed in between songs.

The Anthology made it possible for anyone to hear a stunning variety of musical genres, content, singing styles, and emotions montaged together as old-time music.*

Though it would still be a few years before economic inequality and the civil rights movement became dominant topics of American life, poverty and race had long been subjects of American conversation. But when Smith’s recordings from out of the past appeared, with their messages from people whose voices had not been heard so directly, so vividly, or at all, it was shocking. These songs were evidence of ways of living and performing not found in history books or even among the urban folk revivalist singers themselves. “You didn’t see at the time how preachy the mainstream Folk Movement was,” John Cohen said,

because everybody was becoming a preacher. It was more like a pyramid club; every folk singer became his own preacher. People had this attitude of “I will now speak for Black People.” Rather than listening to what blacks in this country might have to say for themselves. The voices on the Anthology are of complaint and suffering and humor and caustic comments on the world. And documentary depictions rather than moralistic statements…And in a strange way, the Anthology was also a tremendous foundation for the counter-culture.

*

Even though the sons had been recorded only some twenty years earlier, technology and tastes in music had changed so radically by 1952 that the recordings chosen by Smith were often referred to as if they were archeological finds, the sonic equivalent of the Dead Sea Scrolls or the Rosetta stone. That year the pop hits were the usual mix of love songs of longing and emotional insecurity (“Cry,” “Auf Wiederseh’n Sweetheart,” “Half as Much,” “Wish You Were Here,” “I’ll Walk Alone”). But faux versions of songs from outside the mainstream of pop were also finding their way onto the hit lists: Latin (“Kiss of Fire,” “Blue Tango,” “Delicado”), the American West (“High Noon”), Cajun (“Jambalaya”), and blues (“Blacksmith Blues”). Before the Anthology, most people in urban areas thought folk songs were the Weavers’ spirited, jukebox-aimed tunes with Gordon Jenkins’s pop arrangements; the earnest, uplifting, and mildly political messages of Pete Seeger; or Burl Ives’s easy-listening Americana. Folk singers and scholars of folk song alike were suspicious of what was then being called country and western music. Neither they nor the public were aware there were other kinds of working-class commercial recordings. The Anthology made it possible for anyone to hear a stunning variety of musical genres, content, singing styles, and emotions montaged together as old-time music: ballads, work songs, blues, parlor tunes, raw banjo pieces by Dock Boggs, the dark jeremiads of Blind Willie Johnson, hymns from the Alabama Sacred Harp Singers calling from the deep past. For the first time Cajun songs in French could be heard outside their territories (“Pete Seeger couldn’t understand why I was issuing those things, ‘cause he felt they were out of tune,” Harry said. “But once he went to Louisiana, he got back here, rushed up and said, ‘Hey, Harry, you were right! They do sing like that!’”) Dave Van Ronk said that the Anthology was a response to those who sang folk songs as if they were art songs, as a kind of classical music from the lower end of society. Though few noticed it then (or now, for that matter), the performers were not what people would have thought of as folk: Smith’s choices included a Hollywood movie cowboy, an Appalachian lawyer, and city factory workers.

There was also something of a perverse authenticity in knowing that the songs in Harry’s Anthology were not recorded by a folklorist for historical or academic reasons, but by record companies who intended to please diverse buying publics out in the hinterlands of America. In a time in which high-fidelity recordings had just appeared, promising “living sound,” the scratching thinness of these old records seemed like the sound of history, the voices of the dead. But at the same time, their sonic crudeness was a reminder of how challenging they were to record and thus bought with them an aura similar to early photographs of Abraham Lincoln or Civil War soldiers.

The reissue of this music may have come as a shock to the companies whose recordings were made for profit alone, not for presenting it seriously as music. In 1952, they would have been reminded of a part of their own forgotten corporate history as they remade their image, broadening sales by merging country and western music with pop trends like crooners, the use of professional songwriters, and the development of high-fidelity recording.

__________________________________

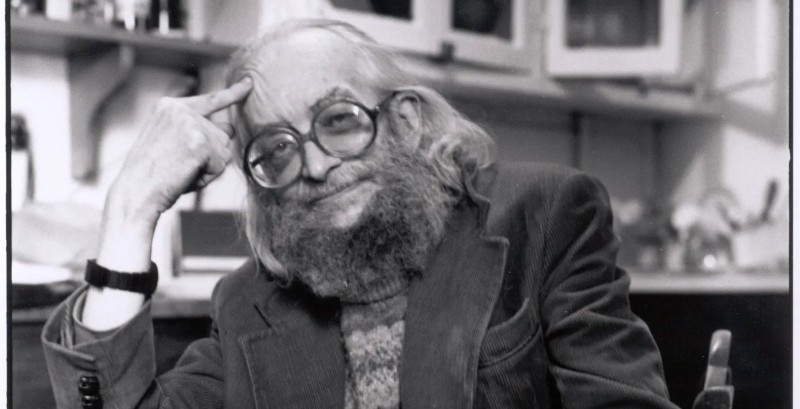

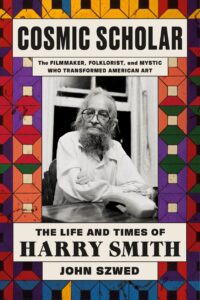

Excerpted from Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith by John Szwed. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.