How the Fire That Destroyed My Paintings Turned Me Into a Writer

Jonathan Santlofer on Art, Career Changes, and the Joy of Something New

In 1990, I had a retrospective exhibition in a Chicago gallery—ten years of my artwork collected from museums and private collectors, along with my six newest paintings. An honor, though I did not want the show. I felt too young for a mid-career survey, put it off twice, but finally gave in.

On opening night there was a major snowstorm and few people showed up, a handful of brave Chicago friends, the art dealer and his wife. Not much of a party, though we drank a lot of wine. The next day flights were delayed, and it was not until evening, slightly hungover, that I finally boarded a plane.

I know the exact time I arrived home because when I turned the television on, the eleven-o’clock news had just begun. I was unpacking, only half listening to reports of a fire raging out of control on Chicago’s waterfront, when the phone in my studio started to ring. I had a bad feeling even before I picked up the phone and heard my gallery dealer’s choked sobs along with stereo sirens—through the phone and on my television—and knew it before he said, “The gallery is on fire.”

I don’t remember the rest of the conversation, but I watched the building burn down on television, ten years of my art up in smoke.

My art life had changed overnight though I didn’t yet know it yet.

The next day I was awakened by another call, this one from a Chicago reporter asking how it felt to lose my artwork in a fire. I said, “I wanted to be hot in Chicago but not the toast of the town.” How I managed to be such a smart-ass I will never know, though in times of anxiety, even tragedy, I tend to fall back on comedy. My statement became a banner in the Chicago Tribune.

In general, people were kind. Many friends, even curators and art dealers I didn’t know, sent me condolences. My art life had changed overnight though I didn’t yet know it yet. I struggled to paint, even tried replicating a few of the lost paintings (a terrible idea) and questioned why I had become an artist in the first place (something I had never questioned before).

Later that year, when I was invited to the American Academy in Rome, it was a chance to escape. I always say Rome was a great place to be depressed. I could not paint in my airy Academy studio with its spectacular views over the city. Instead, I went to museums and churches and made drawings, copies of great Italian art, something I had never done in art school. It was the beginning of another career (one I could not have anticipated) as a legal art forger.

But there was something else I did in Rome: I started a novel. It was about an artist who had lost all of his work in a fire. When I got home, nearly a year later, I reread it and couldn’t bear the protagonist, a whiney entitled mid-career artist. And so, I killed him. On the page. It was a great exercise and it led me to rewrite the book as a thriller, which became my first novel.

The Death Artist was an unexpected success, and I got a contract for two more books. I had not only survived the fire but had gotten a second career.

*

Writing and painting are very different. When you make a painting, you see it, as opposed to a novel that lives mostly in your head. But the two have similarities, both creative acts about trial and error, painting and repainting or writing and rewriting, both about trying to say something—one in words, one in images.

Being an artist has undoubtedly informed my writing, not only the subject matter, but the way I see the world.

I did not give up painting, though trying to balance two careers became increasingly difficult. Eventually, I opted out of my serious art career in favor of writing though I continue to draw every day.

And there is that ironic side gig I hinted at earlier: making copies of well-known artworks for collectors, something I never imagined I would do but enjoy, inhabiting the mind and hand of another artist, which came in handy when I started writing about art theft and forgery. I knew what it felt like to copy a great painting when I wrote the character of an art forger in The Last Mona Lisa, and I understood the man too, a remarkably gifted imitator who yearns to be a great painter.

Being an artist has undoubtedly informed my writing, not only the subject matter, but the way I see the world. When I go anywhere to research a book, I draw the sights and the people. It’s my way of understanding a place, of really seeing it. I hope it makes my writing visual, and more vivid.

There is also my training as an artist. Other than people who’ve gone to art school, few understand how rigorous it is, all-day drawing and painting workshops, up half the night doing exercises in color and design. That discipline has helped me in my writing life. Hours of drawing, painting, and repainting, have translated into hours of writing and rewriting. In both acts you are constantly making decisions about what goes where, what feels right, trusting your acquired intuition, and the joy (sometimes difficulty) of working alone.

I can’t say I’d recommend a fire, but it changed my life in an unexpected way. It threw me off course, out of my chosen career path and into another. I was knocked down for a while, but then I got up, and without consciously thinking about it, I took stock of what I had and used it as I moved forward into something new, and for that I am grateful.

________________________

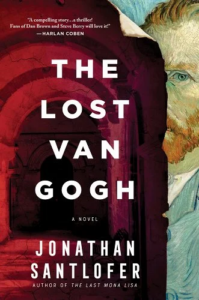

Jonathan Santlofer’s The Last Van Gogh is available now from Sourcebooks.

Jonathan Santlofer

Jonathan Santlofer is a writer and artist. His debut novel, The Death Artist, was an international bestseller translated into 17 languages, a People Magazine "Page-Turner of the Week" and is currently in development at Fox, along with his second and third novels. His fourth novel, Anatomy of Fear, won the Nero Award for best crime novel of 2009. Jonathan created the Crime Fiction Academy as The Center for Fiction. As an artist, Jonathan has been making replications of famous paintings for wealthy clients for more than 20 years. www.jonathansantlofer.com