How the Brothers Grimm Became Martyrs to Academic Freedom

Maria Hummel on the Contemporary Echoes of a 19th Century Power Struggle Between Professors, Students, and the State

Pick any era, and you can name an authoritarian who tried to napalm academia. But you might not know that the brothers who gave the world Hansel and Gretel once became victims and heroes, too, or how the aftermath of their case still matters today.

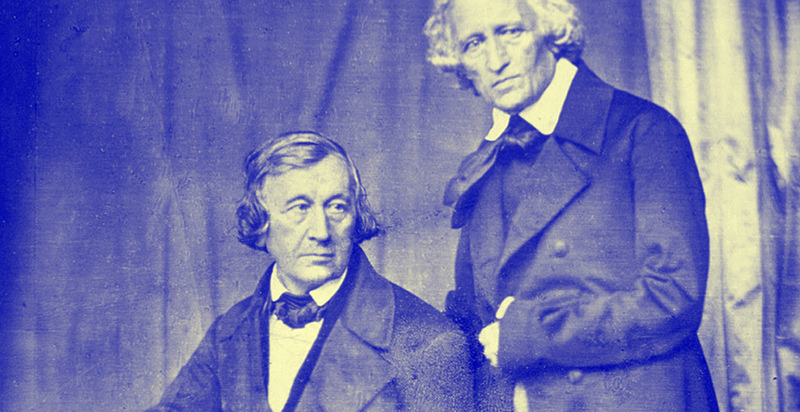

In 1833, professors at the University of Göttingen swore to uphold their kingdom’s new liberal constitution, which decreased monarchal control and gave legislative power to the provincial diet. Two of those Göttingen faculty were Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. No longer the young men who gathered fairy tales for their first collection, the Grimms were now the most famous scholar-mythologists in German lands. They were also about as liberal as a golden retriever is wild. They signed their allegiance as a matter of routine. The university was an arm of the state.

Five years later, their king died, and a new monarch took his place. Ernst Augustus was an absolutist recognized for his divisiveness, trade wars, and extra-marital affairs. Within months, he revoked the constitution and dissolved the diet. Although Ernst Augustus once said he valued “eight hussars more than the whole university,” he now demanded it to kneel.

Although Jacob Grimm wasn’t particularly comfortable as a political icon, he later published one of the more thoughtful tracts in existence on the role of the professor during authoritarian times.

When seven Göttingen faculty members—including both Grimm brothers—refused to pledge their allegiance to the new government, Ernst Augustus called an investigation. At a university judiciary hearing, the rebels calmly confessed: As men of honor, they would not go back on their prior oath. So Ernst Augustus fired them all and gave them a choice: arrest or exile. “For my money I can have as many ballet dancers, whores, and professors as I want,” he later claimed.

The seven’s esteemed university colleagues offered little support, but here’s where things get interesting: the Göttingen students revolted. They took to the streets. Fifty were arrested. Hundreds—reputedly a third of the student body—met in secret to agree on three things: 1) a public letter of respect and approval of their professors, 2) a boycott of all university classes, and 3) a triumphal farewell as their mentors left the kingdom of Hannover. Apprised of the plan, the police forbade anyone in Göttingen to rent horses or carriages to the students. So three hundred students walked to the border. At the river Werra, they unhitched the horses from their professors’ coaches and pulled the carriages themselves over the bridge into Hesse. Across the border, they hosted lunch, toasting their mentors, singing songs.

Thus, abandoned by their elder contemporaries and heralded by the young, the “Göttingen Seven” were born, and would go down in German history for their courage in standing up to dictatorship.

Although Jacob Grimm wasn’t particularly comfortable as a political icon, he later published one of the more thoughtful tracts in existence on the role of the professor during authoritarian times. Maybe it took an elderly woman calling him a “refugee” when he arrived, hauling his own suitcase, in his native Hesse, but Jacob Grimm’s sudden job loss and exile sparked the dissident in him. His 36-page pamphlet is both forensic and passionate. Grimm does not spare his complicit former colleagues, writing, “The world is full of men who think and teach what is right, but when they are called upon to act, they are attacked by doubt and cowardice.”

Grimm also recognizes the flaws on both political sides. He criticizes the leftists for their hasty solutions: “They would like to level mountains, uproot ancient forests, send their ploughs through meadows of wildflowers.” He blames conservatives for stubbornly resisting any change at all. Moderation, counseled Jacob Grimm, is like the heart that warms the body, and factionalism like its cold extremities. But being a moderate does not mean being passive. “How I would have loved to be in quiet seclusion,” Grimm laments, “satisfied with the honor that the pursuit of knowledge gives me.” Instead, he found himself at the center of a crisis of state.

And this is where Jacob Grimm explains the role of the professor with words that still reverberate today: “The open, unspoiled mind of youth demands that teachers, at every opportunity, reduce every question concerning life and state affairs to its purest and most moral content and answer it with honest truth.” There is no room for hypocrisy, claims Grimm. When teaching the youth, you must know your convictions but also live by them. He goes on to declare that most professors realize what’s at stake right now, and that if the university “surrenders without courage” they lose their “right to object.” He acknowledges that some colleagues may act out of fear of losing the university’s precious reservoirs of knowledge, its ability to positively impact society, but says “Academic knowledge preserves the noblest acquisitions of man, the highest earthly goods, but what is it worth against the basis of existence, I mean against our unwavering reverence for the divine commandments?” In other words, in an institution of no integrity, how could the roots of true enlightenment ever take hold?

We lead each other, professors and students. This can only happen in an open society, where both the young and their mentors are able to speak their minds.

Statues and plaques now celebrate the Göttingen Seven, and if this piece were only about them, the story would end here, with the power and eloquence of their resistance.

Instead, it should be noted that the fallout was huge. After Jacob Grimms’ pamphlet was published, the University of Göttingen lost many students, could not hire good replacements, and took decades to recover its prestige.

Meanwhile, the Grimms took a grave personal risk. As young men, their father’s sudden death plunged their family into financial ruin. It was only through the brothers’ wits and years of hard work that they had recovered their social status. To give up their academic positions was to invite another round of penury, this time as men in their fifties. And, despite their powerful connections, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were not hired away by other universities. Few friends defended them openly, and some of their relationships were broken forever. To support themselves, the Grimms began work on a dictionary of the German language, reaching the letter F before their deaths in 1859 and 1863. In the century that followed, their reputations would continue to rise and fall, as the Grimms’ antisemitism and nationalism entwined their legacy with the worst tyranny in German history.

Nevertheless, on a cold December day in 1837, students pulled the Grimm brothers over the river from Hanover to Hesse. They put their own bodies in harness to ferry their professors to freedom. No one knows these students’ names. No one knows their lives. But their act symbolizes something important about higher education. We lead each other, professors and students. This can only happen in an open society, where both the young and their mentors are able to speak their minds. The intolerant left and the authoritarian right have both tried to stifle opposing ideologies in the name of a better society. It’s time to acknowledge this, and for those who still believe in the whole truth of academic freedom to keep pulling forward. Now. Together. We are on the bridge and the river is running fast beneath us.

Maria Hummel

Maria Hummel is the author of five novels, including Goldenseal, longlisted for the 2024 Joyce Carol Oates prize, and Still Lives, a Reese Witherspoon x Hello Sunshine pick, a Book of the Month Club pick, and BBC Culture Best Book of 2018. She is working on a novelization of the life of Dorothea Viehmann, “the fairy tale woman from Zwehrn,” who told the Grimms more than forty tales.