How Texas Prisons Regulate Women’s Knowledge Behind Bars

Kwaneta Harris Explores Systemic Censorship Within the Criminal Justice System

The Lonestar State wants to control women’s bodies, but the abortion ban is not the only way.

It’s 6:07am. Out my window, I see the lady from the mailroom walking with a full cart of items. I skip the five steps to the door of this cell and announce, “Mailroom!” Everyone is excited. When I get books, I’m like a six-year-old on Christmas morning. In solitary confinement, the only pleasure I have is reading. Living in a cell the size of a parking space without a television, tablet, phone, or air-conditioning and an only temperamental radio signal, a book is more than entertainment and much needed distraction. It is a rare moment when I’m not reminded where I am.

The average stay in solitary is seven years. I’m at five and a half.

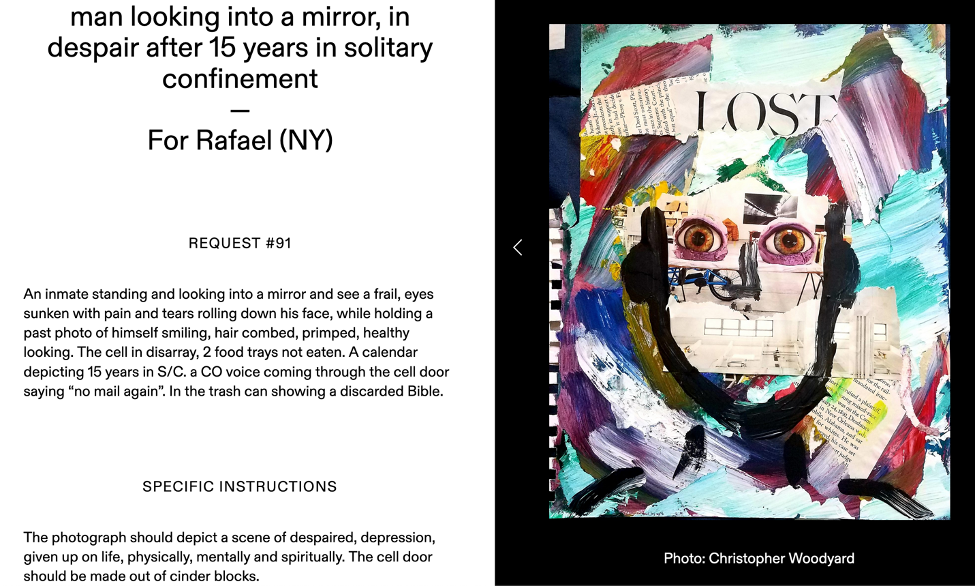

Art for Photo Requests from Solitary, an ongoing project that invites men and women held in long-term solitary confinement in U.S. prisons to request a photograph of anything at all, real or imagined, and then finds an artist to make the image. http://photorequestsfromsolitary.org/91-2/

Art for Photo Requests from Solitary, an ongoing project that invites men and women held in long-term solitary confinement in U.S. prisons to request a photograph of anything at all, real or imagined, and then finds an artist to make the image. http://photorequestsfromsolitary.org/91-2/

People in solitary aren’t allowed to go to the prison library. For some reason, we still receive the (rendered useless) library catalog. If we have been discipline-free for ninety days, we qualify for one book a week, delivered from the library. It’s easy to receive an infraction. Examples include sharing reading materials and/or food with neighbors, covering your windows to block the blazing sun during triple digit temperatures or questioning guards. Whether we request a specific book and author or a generic mystery, romance or humor book, the librarian always sends a Christian themed book. In 2018, I asked her, “Why don’t you give me what I request?”

Books matter just as much for people who don’t and/or can’t read as they do for those of us who do.She said, “I’m called to save your heathen soul.” I’m locked in this cell twenty-three to twenty-four hours a day. Solitary confinement is where we need the books the most. Yet, prisons put up innumerable barriers for people in solitary to receive books.

A recent example: we all heard the rumors, via CNN (Convict News Network) also called the grapevine, that the mailroom posed a “No Sexually Explicit Material” notice in General Population. Nobody paid attention to it. We thought, “That’s for male prisoners.” There isn’t a market for partially nude celebrity photos in women’s prisons. Little did I know, how extreme this notice was to be enforced. In fact, its enforcement redefined “sexual.”

A week prior, I was denied my Good Housekeeping magazine because of a supposedly sexually explicit image. In instances like this, they don’t rip out the offending page. Instead, the entire magazine is denied. The thing is: the image was an advertisement for Depends—the adult diaper. It displayed an older woman wearing a Depends undergarment—which was deemed sexual.

My USA Today was also rejected to a supposedly sexual image—Simone Biles, the Olympic gymnast, wearing her gymnastic leotard. The NY Post was also denied because it contained content regarding former Governor Cuomo. Allure Magazine was denied because of a pregnant woman whose belly was exposed and painted with body paint. A bikini clad model advertising a protein drink led to various magazines—Vanity Fair, CG, Esquire, Cosmopolitan—being denied. The decision is final, and I can’t appeal. These bans are a result of all men at the table, as well. It’s hard to believe a woman of any race, age, political ideology or religion would think a mature woman wearing incontinence underwear would be a sexual image for another woman to view.

But I’m not thinking about any of that as the mail lady approaches my door. I’m bouncing off the walls with anticipation. I’m hopping from one foot to the other. I notice my four books in a neat stack. She pushes a yellow carbon form through the gap in the door as she says, “I’m sorry. You’re denied all four books.” The art book is apparently sexually explicit. The book on menopause includes “sexual images.” The book I wanted on healing from childhood sexual trauma contains terms the prison has prohibited: rape, sexual assault, sexual harassment, sexual abuse and… sex. The book on prison abolition is denied because it would “incite violence.” My mouth falls and I realize my hand is wet with tears, already freely flowing.

They can imprison our bodies but not our minds, or so I thought.

A solitary confinement cell in New York City’s Rikers Island Jan. 28, 2016. Bebeto Matthews, The Associated Press.

A solitary confinement cell in New York City’s Rikers Island Jan. 28, 2016. Bebeto Matthews, The Associated Press.

I don’t read books. I completely immerse myself in them. As an only child, books were my companion. Inside my relationship with books has grown even stronger. I imagine alternate endings and visualize myself beside the characters. Books also build community with others locked-up. We share books. We debate the plot and characters. Reading is how I remain sane in an environment designed to make people insane. Books matter just as much for people who don’t and/or can’t read as they do for those of us who do. Countless times I’ve stood at the adjoining vent until my feet were numb, reading aloud by streetlight to cell neighbors. Once the book has made the rounds, I donate it to the library. We call it ‘donating to the Bermuda Triangle’ because you’ll never see a donated book in your own prison library. We’re told the books go to Huntsville, Texas where they’re redistributed to various other prisons.

The effects of information control on imprisoned women are intimate and profound.Prior to solitary, my cellmates would hear me chuckling as I read and ask me to read aloud. It became a routine we called “story time.” During that time, I lived in the “long timer” dorm—a place reserved for people with a minimum of fifty-year sentences. The long timers who wanted to learn or improve their reading were forbidden from attending the prison offered schooling. The state doesn’t see the value in teaching a person with a life sentence whose ineligible for parole, or who’s serving three life sentences, to read. Many people inside struggle with reading but shame and embarrassment forces some to choose even solitary over the embarrassment of being recognized as a struggling reader.

I remember a lady named Tameka. She’s been incarcerated since she was fourteen and was reading at a level where she only recognized sight words. One day, she was talking in her reading class and the teacher reprimanded her saying, “If you shut up maybe you can learn to read.” The class giggled. Tameka was twenty-five and she immediately began doing anything to get placed in solitary. That was her last day in class. She would rather be in solitary than be embarrassed because she hadn’t been taught how to read.

I couldn’t do my time without reading. Usually, I hear about a book I’m interested in by listening to NPR or reading a review in a magazine. First, I write the prison mailroom to determine if the book and author are approved by the state. If so, I place it on a list I have for friends and family to purchase as gifts for holidays and special occasions. It’s not a fail-safe. I’ve had books arrive and the status has been changed from approved to denied. No appeal is permitted.

Sometimes, it’s the mail lady who flips through pages at the door to your cell and reverses the decision. A neighbor could order the same book a week later and have a different mail lady who permits the book. It’s within their discretion. If they won’t let me have a book, I’m given a choice. They can destroy the book or, I can pay to send the book to someone on the outside. I’m lucky. I can usually afford to send them home. This involves purchasing a large envelope and eight to ten stamps per book. People inside can only purchase thirty stamps every two weeks. Spending ten stamps to mail one book is a big deal. Not everyone can do this. Times are hard. No one has money to waste.

The culture wars and political divisiveness have affected us in many ways in prison. Many of the books I read just a few years ago are now restricted under a new category termed “promotes racial division.” I believe this is a by-product of the Black Lives Matter Movement.

History warns us of the dangers of banning books but the effects of information control on imprisoned women are intimate and profound. The majority of women living in solitary confinement were transferred from juvenile prison. At that age, talking back to prison staff or arguing about their treatment would be punished with time-out. However, once people turn seventeen, talking back or arguing earns a new charge and conviction of assault. This results in additional sentence time, transfer to solitary confinement in an adult prison. Being an adult in prison paradoxically means even less freedom.

Many women in solitary were therefore in juvenile facilities when their menstruation began. This means, many incarcerated women don’t have basic knowledge about our bodies and how they work. We don’t have google. Books that can answer these questions are banned—as they are deemed “sexual.” This leaves not just younger women but my fellow menopausal friends and I to fall back on what was and often continues to be taught in public schools—the abstinence and fear-based lessons that boil down to three commandments: Don’t touch your privates; Don’t touch other’s privates; Don’t let others touch your privates. Following these rules makes people perfect victims for sexual predators and preventable illnesses. It’s misinformation masquerading as education. The Lone Star State isn’t satisfied by banning abortions to control women’s bodies. It’s also forbidding us knowledge needed to prevent one.

__________________________________

From Books Through Bars: Stories from the Prison Books Movement, edited by Dave “Mac” Marquis and Moira Marquis. Copyright © 2024. Available from University of Georgia Press.