How Tennis Helped Me Manage the Competitive Beast That Was Ruining My Writing

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya on Finding Balance Between Drive and Acceptance

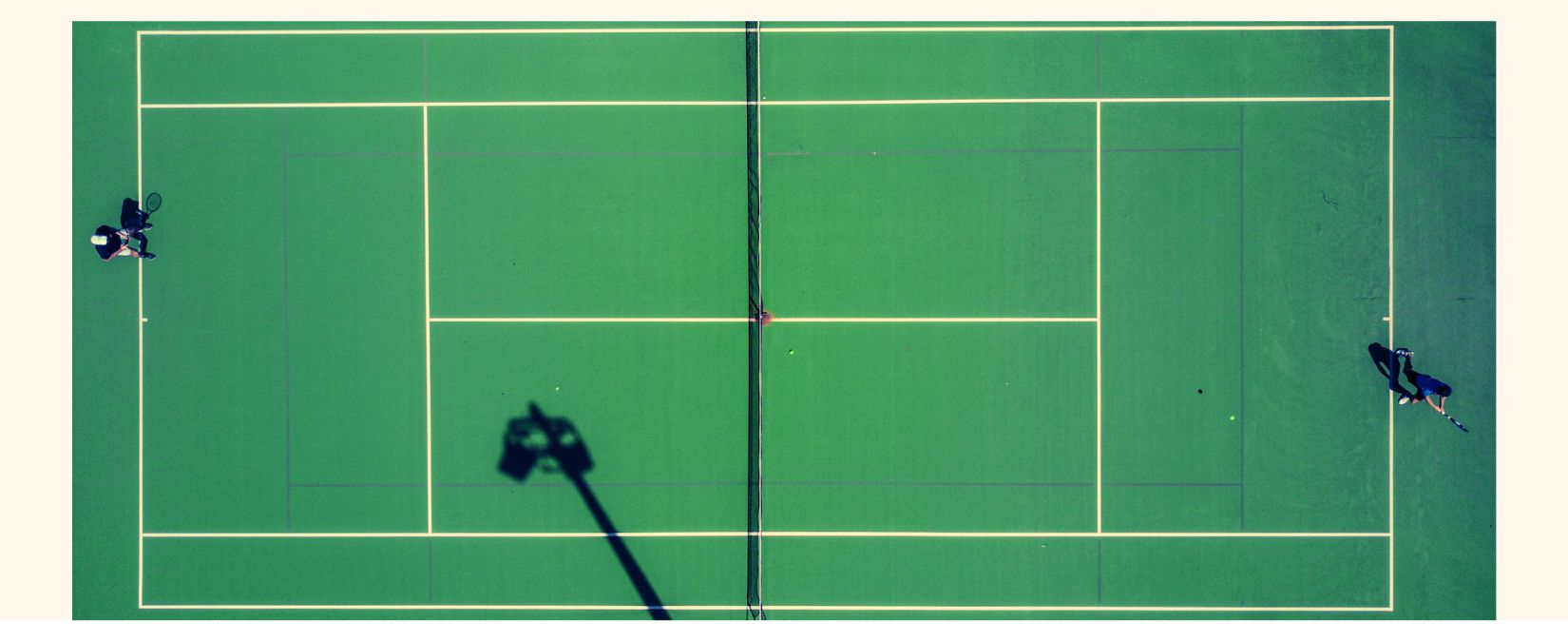

I’m in a tennis losing streak. The last three singles matches I played, I lost. Badly. For each match, I know why I lost and what I need to work on. That doesn’t make the losses any less frustrating, especially since the three players who bested me all have different games, exposing different weaknesses in my own. I was not humiliated by these matches, but I was humbled. I cursed on the court, under ragged breath. I chastised myself in the third person, an impulse only tennis brings out in me, one I used to mock in others. I ran down every drop shot but made some abysmal unforced errors on approach shots. I didn’t double fault more than my self-allotted limit of one per set, but my second serve is weak right now. I lost and lost and lost.

Well, at least you got a breadstick, my teammate said after a match, referring to the sole game I won in the entire match. Breadstick’s better than a goose egg, but barely.

I’m in a writing losing streak. Or, at least, that’s what I would have called it a few years ago. Residency rejections pile up; I haven’t had a new short story published in over a year. An essay pitch I thought was air tight received a swift rejection from the editor (I send out these types of rejections almost daily as an editor myself, but that doesn’t make being on the other side any easier).

But this isn’t a sob story about tennis or about writing. You see, I would have called it a writing losing streak before, but I would never say that now. A writing career isn’t measured by wins and losses.

Save that shit for the court, Kayla.

*

When I returned to tennis last April, I hadn’t hit a ball in a decade and was double the age I’d been in my prior tennis prime. I warned my wife: If I start playing tennis again, it won’t just be a hobby; it’ll become an obsession. I’ve never been someone to do anything at 50 percent. Sure enough, weekly clinics became twice-weekly became a mix of clinics, private lessons, and round robins. All along, I knew I wanted even more than that. I wanted competition, craved it.

I bounced from coaching pro to pro, never really finding one who understood my goals. I wasn’t delusional; I knew I wasn’t joining the national tour at age 32. But I also knew if I felt the way I felt, craved the competition I craved, then there were other players at my skill level who did, too. Sure enough, I found my people.

I do get frustrated at myself when I’m losing. It overwrites my body language, makes me slump and shuffle my feet, cross my arms tight.

By summer, I was preparing for my first USTA singles tournament. By fall, I’d joined three leagues: a recreational women’s doubles league, a singles flex league where I play just for myself instead of as part of a team, and a USTA league. I still haven’t found a pro who entirely understands what I’m after, but that’s okay. I’m going after it anyway.

For a while, I won a lot. I went undefeated on my first USTA team. As good as it felt to win, I could feel myself getting bored and, worse, my skills plateauing. I had improved faster than I thought I would when I began rebeginning the sport, and it was now evident I was playing down. At the end of the season, I moved up to a new team and more competitive level of play. I haven’t won a singles match at that level yet. It’s still a goal to eventually move up further.

This losing streak has been challenging. I’ve been competitive my entire life. As a teen, I would have boldly claimed this trait, this compulsion. As an adult, I backed off of it. It felt obnoxious to be loudly competitive. Cringe. What I saw as a source of power in my youth I later decided was a personality flaw. Nobody likes the most competitive person at game night.

Compulsions, though, are difficult to quell.

And sure, I’ve played games with people whose competitive nature spoils the game for themselves and for others. They over-celebrate luck-based triumphs and get into petty arguments. Their anger only further fucks with their focus, and then they lose even worse. I’m all for a little fun trash talk, emphasis on fun. But you know the type. Sometimes I fear I’m one of them. I do get frustrated at myself when I’m losing. It overwrites my body language, makes me slump and shuffle my feet, cross my arms tight. But I never let it ruin my enjoyment of the game itself, never lash out at others or quit prematurely. I try to keep myself in check. Over time, I’ve cultivated my competitive nature so that it doesn’t mean I have to win but that I want to win. It feels like an important distinction.

It took until recent years to understand my aversion toward the word competitive. It’s not simply because I’m afraid to be the asshole no one likes at game night. It’s rooted more deeply in, well, the deeply embedded societal contexts most of my hangups are rooted in: heteropatriarchy and internalized sexism and homophobia.

Women aren’t allowed to be competitive the way men are.

When it comes to sports, that was quite literal for a long time, women relegated to recreational and amateur play and barred from professional leagues. Tennis was at the forefront of the formation of professional women’s sports leagues. The Women’s Tennis Association was founded in 1973, 23 years before the WNBA and 28 years before the first pro women’s soccer league.

While I no longer see it as a personality flaw, I’ve learned my hunger for competition must be tended to and guided in the right direction.

Sports history aside, competitive women have long been denigrated by society, competition in women even more maligned than ambition. I get it; a competitive disposition can be ugly. But rarely have I ever seen boys or men back down from their ugliest competitive urges. It’s baked into what’s deemed as healthy socialization for them. By quieting my own competitive urges, wasn’t I just playing into these gendered expectations and rules? Fuck that.

And maybe there are times when I want to be ugly.

Even worse than a competitive woman, I’m a competitive dyke. This bifurcated my internal battle with my competitive urges as a young adult struggling with my lesbian identity. I was fighting two fights at once, attempting to squash the internalized sexism telling me women couldn’t be competitive and fearing my desire for competition made me like a man, that is, unlike a woman. If I embraced my competitive nature, I’d have to embrace the other parts of my nature that went against how I was taught a woman should act and be. If I opened the gates to desiring competition, all the other desires would come out with it.

Coming out does a lot more than clarify your sexual desires; it often clarifies and makes possible all the most authentic parts of yourself, work that takes effort and time and mistakes but is ultimately affirming and healing far beyond repairing sexual shame.

So, yes, I’m a competitive person—a competitive woman, a competitive dyke—full stop.

Billie Jean King, a famously competitive dyke, founded that first women’s professional tennis league, by the way.

*

While I no longer see it as a personality flaw, I’ve learned my hunger for competition must be tended to and guided in the right direction. If left to its own whims, it devours recklessly, and I become the type of competitive person nobody likes, not even myself. There is a time and a place for competition, and let me tell you: Writing is not it.

Prior to my return to tennis, I experimented with all kinds of competitive outlets to distract myself, though I didn’t know that’s what I was doing. I bowled. I played darts in bars. But there’s only so many times you can go to a bowling alley or a bar with darts in a month. It’s like I knew it before I could name it: If I didn’t get my competitive nature out somewhere, it’d show up where it doesn’t belong, and I desperately didn’t want it showing up anywhere near my art. I love the ugly beast inside me; I just have to be careful about where I let it out to play.

Coming out does a lot more than clarify your sexual desires; it often clarifies and makes possible all the most authentic parts of yourself.

I took writing rejections hard when first submitting short fiction to journals. I held a lot of these thorny feelings inside, embarrassed by them, used to being a self-assured person even in the face of setbacks. I gave good rejection advice, all while not heeding it myself (is there anything more writerly than that?). I engaged in some erratic rejection behavior I’m not proud of, looking up the people who won fellowships “in my place,” as if that’s how it worked.

It’s not that I wanted to dismiss or disparage other artists; I just wanted to know what they had that I didn’t, how I could improve and get it next time, as if there were some kind of formula for it all. More than anything, it was an exercise in self-harm and a troubling perpetuation of all the ways capitalism poisons art. It went completely against everything I believed about writing and creative practice: that it is buoyed by a collective and communal mindset. Not a competitive one.

I had been applying the same practice of tennis post-match analysis to my writing life, but this was before I’d returned to tennis, before I had a true outlet for the kind of competitive calculations I was conducting in a place that has no use for them. Competition stifles creativity; it does not nurture it. But that beast within me had nothing to feed on, and so it feasted wildly, eating at my own judgment and self-awareness. If someone had accused me of treating other writers as my competitors, I would have denied it, all the while engaging in activity proving their point.

Almost all the close relationships I have are with writers or artists of some kind. I’ve seen loved ones, even some who wouldn’t consider themselves competitive, cycle through feelings of angst, anxiety, even anger while comparing their careers to others. I am not alone in my (former) tendency to “look up the competition,” so to speak. “Wins” and “losses” in the writing world are fleeting, fickle things. Awards, lists, reviews, there are so many conventions that trick us into a competitive mindset. But we have to remember they are separate from art and the making of it.

Playing tennis has created an abundance of energy in my life, not a scarcity of it. I’m no longer as fixated on traditional markers of success.

You can compare and contrast yourself to all the authors who have books coming out the same day as you, but what is the point? They only share a pub date with you because of a confluence of random variables. When you don’t get a residency or an award, it might be a setback, but it isn’t a loss. Because this isn’t a game! It is your life; it is your art. So many of these things are an absolute crapshoot, more akin to playing blackjack than playing tennis. Talent isn’t enough on its own; you also often need a little luck—or a lot of it! We shouldn’t break our writing lives into wins and losses at all; to do so is, well, a losing game.

I had to return to tennis to figure all that out, to name it. With tennis, as with any sport, the fact of winning or losing is well defined and easy to understand. Sure, there are moments when I feel like I’m getting beat by a player I know I’m better than, but it still isn’t a mystery as to why I lost. There’s always a reason, sometimes as simple as how rested I am, how compatible their strengths are with my weaknesses. And analyzing a loss post-match is far more meaningful and useful than ever trying to analyze why I didn’t get this or that writing thing, which I stopped doing once I started playing tennis competitively. The beast got fed on the court. It didn’t have to eat through the rest of my life anymore.

*

It’s not just my relationship to rejections that tennis has fixed when it comes to my writing. Tennis is making me the best version of myself, sharpening my relationship with my body which, in turn, makes my mind a more livable place. Laura van den Berg recently wrote in Fight Week, her newsletter about writing and competitive boxing:

Sometimes people ask me if I worry about boxing taking time away from writing but boxing has so totally rehabilitated how I treat myself and how I organize my time that I now have more energy to give to my work and not less.

I have found this to be true of tennis, too. The two hours I spend playing tennis in the morning does not take two hours away from writing; it makes it so that when I sit down to write another time, I’m more ready for it, more present and fueled. Playing tennis has created an abundance of energy in my life, not a scarcity of it. I’m no longer as fixated on traditional markers of success, on writing “wins.” And I’m full of creative energy created by physical activity and the mental grind of (healthy!) competition. These factors combine to make it so my writing is stronger than ever. My writing goals, like my tennis ones, are ambitious and set entirely by myself, not anyone else.

The relationship between tennis and my writing flows in both directions. Just as tennis has made me a better and more confident writer, writing has made me a better tennis player, at least when it comes to the mental aspects of the game. One of the most frequent pieces of advice I give to writer friends: Celebrate your almosts. Received a personalized rejection? Named a runner-up to a prize? Made it to the last round of deliberations for a residency before ultimately cut? Those are your almosts, and they should be celebrated, should make you feel good, something to share with your group chat, your writing buds.

The culture of announcing some news on social media has made it seem even more like there are “wins” in writing, but if we only recognize the announcements worthy of social media boasts as real then we lose sight of the almosts. And the almosts are important, I promise. Often, the almosts open a series of doors toward getting the thing you want. That’s the special thing about writing; there aren’t just fixed categories of wins and losses. There are almosts; there are triumphs that feel small because of how social media virality has warped our perception of scale but are actually quite large. When your writing connects with even just one person on a meaningful level, that’s huge.

I started this essay suggesting tennis comforts me in its easy breakdown of wins and losses, but perhaps writing has also been complicating that for the better. The almosts are different in tennis, but they’re there. The really good winner in the match I lost. The ace after a double fault. The loss to someone who then becomes a practice hitting partner, who makes me better.

I prefer to play singles, always have. This was never an issue as a junior player. When I returned to the sport, I had trouble finding women my age to play with. Too many wanted to play doubles. I understand the appeal of partnered play, someone to cover you when you miss, an extra set of legs on the court, all the complex strategizing that comes with doubles. I also think it’s a fallacy that doubles is easier than singles, at least once you reach a high level of competition. It can be easier on the body and require less endurance, sure. But that doesn’t mean it’s easier.

Still, I don’t love doubles, and I’ve clocked the reaction this sometimes gets from people, who assume I either am indeed one of those people who disparages doubles as tennis lite or who doesn’t play well with others. Well, they might be right about that last bit. Doubles isn’t always best for the beast.

Playing singles on a tennis team feels close to my experience of writing. I reject the dominant narrative of the solitary writer. I think the best writers are always working in conversation and in community and that a well lived writing life is not isolating. And yet, much of the work is technically done solo, solo work that fits into a larger ecosystem and collective. This is what being a singles player on a tennis team feels like. I’m in a tennis losing streak, but my team isn’t. We’re at the top of the league. The communal practice and ethos I’ve cultivated around writing helps me recognize that bigger picture.

Failure teaches us so much in writing; fear of it holds us back. I’m working on seeing my tennis failures as open doors toward improvement. When I was playing down, I was never going to get better. I’d rather be in a losing streak at a higher level of play than coast by at a lower one. So, too, I’d rather challenge myself in my writing than play it safe. Losing a match means you’re being challenged, which means you’re getting better. The bar is rising, and you just have to do the work to meet it. I never want writing to feel easy either. This is what I find myself having to explain to people who want to inject AI in the arts.

I don’t want to think of the marketability of my work; I want to write the things I actually want to write and keep getting better at it. I want to be unmarketable—at least by traditional standards—just as I want to defy the common expectations of how a thirty-something amateur tennis player should approach the game, should approach competition.

I’m not saying all writers need to play tennis. I also know there are plenty of artists who don’t struggle with the competition beast, who are able to look beyond the binary of wins and losses comfortably, without an outlet. But if you do struggle with this particular beast, find a place to let it roam freely. Cultivating a writing practice is necessary to the work we do, but often cultivating a separate practice around the edges of it can unlock even more of our creative potential, whether that’s a sport or gardening or a different artistic practice or baking.

By all means, fight fiercely for your art. But don’t make a sport of it. Because you really will lose every time.

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya

Kayla Kumari Upadhyaya is a lesbian writer of essays, fiction, and pop culture criticism living in Orlando. Her queer horror novelette Helen House was named one of the Best LGBTQ Books of 2022 by NBC News. She is the managing editor of Autostraddle, an assistant fiction editor at Foglifter, and the former managing editor of TriQuarterly. Her short stories appear in McSweeney's Quarterly Concern, Catapult, The Offing, Joyland, The Rumpus, Cake Zine, and others. Some of her culture writing can be found in The Cut, The A.V. Club, Vulture, Refinery29, and Vice, and she previously worked as a restaurant reporter for Eater NY.