How Systemic Racism Leads to a Lifetime of Self-Imposed Isolation For Black Americans

Chad Sanders on Learning to Process the Societal and Psychological Effects of Anti-Blackness

In my corporate journey that started at Google, and now in my trek through Hollywood, I’ve felt the damaging effects of Black isolation, once mandated by slave codes, that remains in our country’s cultural fabric. The signals that we must separate and move alone if we want to ascend are so subtle that it’s hard to prove—to ourselves and others—that they’re real.

How can I explain to someone that my white colleagues at Google looked at me differently when I sat with other Black employees at lunch? How can I get someone to understand that Phil Jackson is dismissing LeBron and his Black business partners as some sort of juvenile gang if the person I’m trying to persuade would rather not see what’s there?

White supremacy doesn’t just want Black people to suffer, it wants us to suffer alone.

Many deride the competition between Black people climbing in our careers, trying to get the big job and the big check. Personally, I feel the tension between my spirit, which wants to love and connect with other Black people in all environments, and my mind, which tells me that our opportunities are finite and that I have to be that one, special Negro to get that next greenlight, that bonus, that promotion. That competition between us seeds profound loneliness.

When I read the Alabama Slave Code in the museum, I was heartbroken. As familiar as I am with the evils of this country and the way it treats Black people, that ordinance revealed something darker than slavery itself: White supremacy doesn’t just want Black people to suffer, it wants us to suffer alone.

When I’m alone in the park in a white neighborhood, I’m more vulnerable to a predator. When I’m alone in a business meeting with executives and fast-talkers, I’m more vulnerable to take a bad deal. When I’m alone in a corporate office, I’m more vulnerable to be told I’m misinformed, undereducated, or crazy.

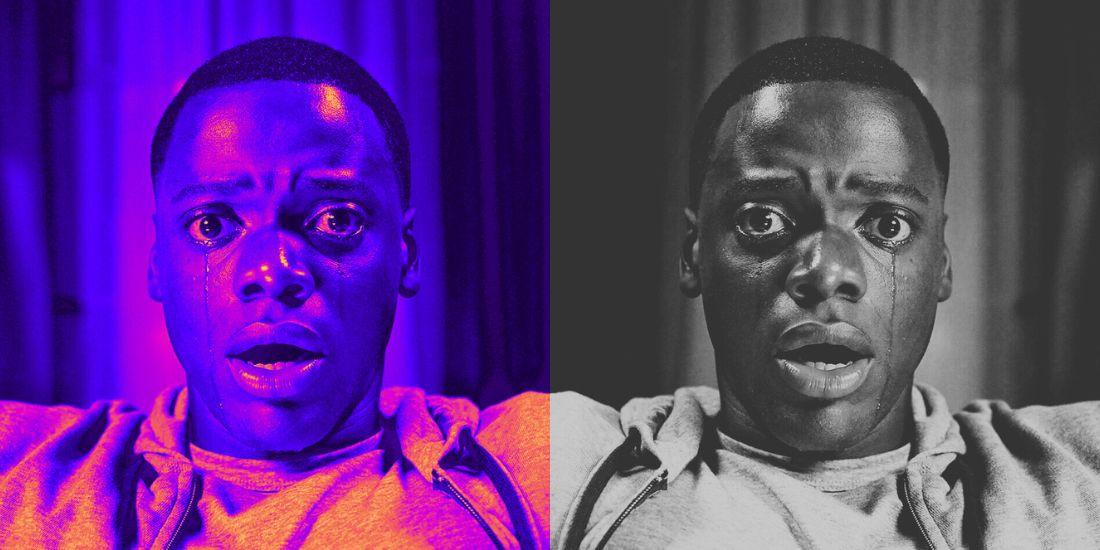

Jordan Peele portrayed the life-and-death stakes of Black isolation in his magnum opus, Get Out, in which a young Black man named Chris is preyed on, captured, and almost decapitated by his white girlfriend’s family and their community because he’s isolated from his people and susceptible to gaslighting. In Peele’s film, the only two people who try to save Chris are both Black: first, another Black captive who yells at Chris to GET OUT, affirming Chris’s suspicions that something dangerous is afoot. And finally, in the film’s closing minutes, the protagonist is saved by his Black friend Rod, who drives all the way from the city to the suburbs to save him.

The message of the film is poignant: Isolated in whiteness we are at incredible risk. I felt the pain of that isolation even before I understood it in my early twenties working in a Silicon Valley cubicle. I felt that pain in the hotel lobby in Florida on “vacation.” I felt it in Forest Park, alone with Gary as my tour guide. I felt that pain of isolation in the hotel lobby in Israel while Ira and a few others chortled at me and people like me as the butt of their joke. I feel it every time I walk into a place where Black people are made to feel unwelcome.

When I enter spaces among the white and privileged to try to seize opportunity, I’m so often isolated, with no one else like me to affirm my experience, which leaves me susceptible to gaslighting. Black people have experienced gaslighting—being made to question our sanity—for centuries. The conversation around Black people being gaslit in the workplace, where we go to earn, has gotten louder in recent years. I know that. I feel it in the moment. But so often I just shrug off the bad feelings to make it through the day, the week, the year.

But I can feel that these experiences damage me over time. So, I asked my friend Amanda Jurist, a licensed clinical social worker and family therapist, about the effects of isolation and gaslighting. We connected on a Zoom call where she walked me through some of the physical and psychological effects of these common experiences for Black people.

“Being in a setting where you’re constantly gaslit creates a person that is extremely anxious. Highly depressed. Disconnected from their body,” she said. “They might start to experience symptoms such as tingling in the hands and feet. You might experience shortness of breath. I get a lot of people describing this feeling of a knot in their chest. There’s nothing technically, medically wrong with the individual, but because they’re so emotionally bound because of the gaslighting, they’ve learned not to trust themselves. Because someone’s constantly convincing you that what you’re experiencing is actually not happening.”

I thought about times I’ve been surrounded by whiteness in classrooms and offices, times when I was poked, belittled, and insulted by white people but unable to trust my feelings enough to defend myself. These were times when I’d look around the room to see if anyone else felt what I felt or recognized that I was under attack, and all I’d see were uninterested and unempathetic white faces. And so instead of defending myself, I froze, doubting my own feelings, and then later I doubted myself for being unable to protect myself in the moment.

Amanda continued to explain the physical damage that these experiences can have.

“So [the person] is emotionally bound in a way where there can be this tightness, this tension carried in the chest area. I’ve heard people, especially women, describe this feeling of gasping for air and feeling like they’re having a heart attack, but it’s really a panic attack. So they’re still operating and doing their job in this state of panic and tension and angst. That’s why they get used to living in that space. Operating outside of that becomes very, very foreign. It becomes typical to have a very anxious work experience and carry that very anxious experience into personal relationships with family and friends as well. So it causes tremendous pain.”

So often Black women are called crazy. So often Black men are called angry. Maybe this is why we seem that way to people who don’t understand our experiences. As I listened to Amanda, speaking in her gentle but clinical and deliberate voice, my body shifted around. I noticed the stiffness in my neck, back, and shoulders. I could feel the tension I was living with from more than thirty years of these harmful experiences that began in childhood.

I made processing race trauma for public consumption my job because I wanted the money so bad.

But until this conversation I had never taken much time to examine the effects of all those moments of isolation and gaslighting. And until a few years ago I had never tried therapy, or anything else healthy, to deal with the long-term feelings of loneliness, stress, and anxiety I have suffered from years of enduring anti-Blackness and white supremacy. I was reluctant to try therapy because it’s expensive and only 4 percent of mental health professionals are Black. I couldn’t trust someone who isn’t to help me deal with these difficult and complex feelings. There are many Black people who are similarly reluctant to try therapy. Only 9.8 percent of Black people in the US receive mental health treatment.

But Amanda tells me there are important reasons why Black people avoid therapy to deal with our internal and physical pain besides the steep costs of treatment and the lack of Black mental health professionals.

“When you think about Black, African American individuals, the experience of slavery, the results of what that did to our people and our communities are just endless. The pain, the dehumanization, the pattern of internalizing yourself as the oppressed. And also experiencing oppression, racism, Jim Crow, segregation, these structural systems that continue to put Black Americans at a disadvantage. It is actually unsafe for someone to sit down and ask a person who is going through that much trauma to bare their emotions. If we think about a woman or a man on a plantation, there was no way that there was room to ask them how they felt. Do we really want to know what they felt, and could the psyche actually hold what would come up? There’s no space for it from a survival standpoint.”

Now Amanda was revved up. Her tone grew more passionate, more grave than before.

“So you see that kind of evolve. We’ve moved ahead in some areas, but still we’re just focused on how to put food on the table, how to keep a roof over our heads, how to fight to get our children educated. We do not ask how we feel. ‘When a feeling comes up in this house, it better stay in this house, and we’re not getting into it.’ It’s a survival tactic. And so fast forward to now, we’re still there. We haven’t outgrown that state.

“Some people are so embedded in their trauma that we have to be very careful about the therapy they’re even able to engage in because opening them up too wide can actually be detrimental to them.”

Amanda is telling me that processing the trauma from slavery and racism and anti-Blackness can be harmful to someone focused on trying to earn and survive and move forward. I’m that exact kind of person, the person focused on earning and forward movement. The person for whom processing race trauma can be dangerous. And I made processing race trauma for public consumption my job because I wanted the money so bad.

__________________________________

Excerpted from How to Sell Out: The (Hidden) Cost of Being a Black Writer by Chad Sanders. Copyright © 2025 by Chad Sanders. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Chad Sanders

Chad Sanders is the author of Black Magic: What Black Leaders Learned from Trauma and Triumph. He is the host of the Yearbook podcast on the Armchair Expert network and the Audible Originals podcast, Direct Deposit. Chad’s work has been featured in The New York Times, Time, Fortune, Forbes, Deadline, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. Chad has also written for TV series on Max and Freeform. Chad was raised in Silver Spring, Maryland, and earned his BA in English at Morehouse College. He lives in New York City.