How Suzanne Valadon Reclaimed Her Image By Painting Herself Naked

Jennifer Higgie on the Remarkable Life of a 19th-Century Model-Turned-Artist

If anyone has the right to depict herself naked, it’s a model: those nameless women whose faces and bodies have sold countless paintings over the centuries, and whose lives we very rarely know anything about.

Born Marie-Clémentine Valadon in 1865, Suzanne Valadon, as she would become, was the illegitimate daughter of Madeleine, a seamstress and cleaning woman, and a father she never knew. In 1870, still shamed by giving birth out of wedlock, Madeleine moved her family from their home of Bessine-sur-Gartempe to Montmartre. It was a turbulent time; France was embroiled, and then defeated, in the Franco-Prussian War and the Third Republic was established in 1877.

For seventeen years, under the direction of Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Paris had been a vast building site, transformed from a medieval city into a modern one; 12,000 buildings had been knocked down, displacing thousands of the city’s poorer citizens. High above Paris, Montmartre, however, was left untouched. Attracting refugees from the city centre, this vibrant working-class village—full of gardens, bars, cafés and studios—fast became the epicenter of modern painting.

Reports differ about her early years, but it’s generally agreed that after a rudimentary education, from around the age of ten or twelve, Marie-Clémentine, who had made drawings on anything she could find for as long as she could remember, earned a living doing various jobs: sewing, making wreaths, selling vegetables, waitressing, washing dishes and working as a stable hand. Her dream, though, was to become an acrobat. She was a “wild, tiny figure [. . .] bobbing along on a horse’s back, executing handstands, headstands, somersaults and cartwheels.” She recalled: “I thought too much, I was haunted, I was a devil, I was a boy.” She worked for six months at the Cirque Fernando, Montmartre’s permanent circus, but when she fell from a trapeze at the age of fifteen, her focus turned to art.

Initially with the help of her friend Clelia, who was a model, from 1880 to 1893 she posed for artists including Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and others. She is the star of some of the era’s most famous paintings: Puvis de Chavanne’s The Grove Sacred to the Arts and Muses, Renoir’s The Large Bathers, Dance at Bougival and Girl Braiding her Hair, and Toulouse-Lautrec’s The Hangover. She is pictured variously as a mythical creature, a naked temptress, a sweet-faced coquette, a virginal beauty and a sour-faced drunk. As she struck poses, she observed how the artists sketched, prepared their palettes and mixed paint. She was learning her craft.

Maria, as she was known, frequented the cafés and nightclubs of Montmartre: the now legendary Lapin Agile, the Chat Noir, the Café de la Nouvelle Athènes—favored by the loose group of artists known as the Impressionists—and others. The only other model of the time who became well known as an artist, Victorine Meurent—the star of many of Manet’s paintings, who was twenty years older than Maria—was also a regular. Maria was high-spirited and bored by convention: she once entered the Moulin de la Galette by sliding down the bannisters, dressed in nothing but a mask. She became close to the charismatic Spanish critic and artist Miguel Utrillo; not to be outdone, he rode a donkey backwards into the same nightclub and wheeled a barrow of fish into the elegant L’Élysée Montmartre. Maria followed him, laughing.

In 1883, Maria gave birth to her son, Maurice, who was also to achieve fame as an artist. It’s not clear who the child’s father was but in 1891, Miguel Utrillo “acknowledged” him, perhaps more out of kindness than patrimony: it was impossible for Maria to marry or to be considered respectable as long as she had an illegitimate child.

Not long after Maurice was born, she drew a head-and-shoulders self-portrait in charcoal and pastel.

For once, no one is looking at her but herself.

She is eighteen, the new mother of a child born out of wedlock. She is working class and desperately poor. Yet, she depicts herself with pride: her golden hair is neatly pulled back, her blue dress demure. She looks out at us—or at herself in the mirror—with a clear, stern expression. She is a beauty, but she underplays her looks. Her signature in the top right corner is firm: Suzanne Valadon, 1883. Curiously, though, when she made this drawing, she was still known as Maria, not Suzanne, so it’s likely she signed it later.

She is working class and desperately poor. Yet, she depicts herself with pride: her golden hair is neatly pulled back, her blue dress demure. She looks out at us—or at herself in the mirror—with a clear, stern expression.

Around 1895, Maria became Suzanne. Toulouse-Lautrec chose her new name after the biblical story of Susannah and the Elders—the painting that Artemisia had so furiously painted almost 300 years earlier. From our perspective, it’s a horrible thing to do: to name a young woman after another young woman whose fame rests on the fact that she was sexually assaulted by older men. But it stuck: she liked it and it was hers. She and Toulouse-Lautrec were close, most likely lovers: she posed for him and he was the first to recognize her talent as an artist. He pinned three of her drawings to his studio wall and asked his visitors to guess who made them. He also let her borrow his books: she read his copies of Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, Ludwig Büchner’s Force and Matter and Baudelaire’s poems.

Despite her formidable talent, Suzanne’s reputation as an artist was, until very recently, clouded with tedious moralistic judgements about her virtue, or rather, her perceived lack of it. As one of her biographers, June Rose, wrote: “Long after she became an artist herself, these images of her, beautiful and dissolute, lingered in the minds of critics, and her own conduct as a woman cast a shadow over her achievement as an artist.” It is galling to compare her reputation with her male contemporaries’, very few of whom lived what could conventionally be called blameless lives, and whose paintings are rarely judged by the behavior of their creators.

As a female artist in Paris at the turn of the century, Suzanne wasn’t alone. Like Paula Modersohn-Becker and Gwen John, women gravitated to the city for its relative freedoms and the richness of its art scene. In 1879 alone fourteen women had been awarded gold medals at the Paris Salon. Various movements came and went at the turn of the century—Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Orphism, Dada and others—but it was Impressionism which had dominated the Parisian art scene from the 1860s. Discussing her influences later in life, Suzanne admitted that it was “the palette of the Impressionists that enchanted me.” The group included a number of brilliant women—Marie Bracquemond, Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzalès and Berthe Morisot—but they came from privileged backgrounds, were roughly twenty years older than Suzanne, and none of them drew or painted themselves naked.

Also, despite their immersion in bohemia, most female artists were still chaperoned; what they were allowed to see and do was tightly controlled. But Suzanne was her own woman: financial constraints aside, she was free to come and go—and to draw and to paint—as she pleased. That said, some of the artists she modelled for, and often slept with, were scathing about the idea of women being artists. Renoir—for whom she modeled for five years—wrote to a friend that: “I think of women who are writers, lawyers and politicians as monsters, mere freaks . . . the woman artist is just as ridiculous.”

*

In the sensual Adam and Eve, Suzanne pictures herself as a smiling, happily naked Eve. Her hair streaming down her back, she plucks the forbidden fruit like a treat to be savored. Adam—modeled by her new lover—gently guides her hand with his; his genitals are hidden by a fig leaf that was apparently added later, to appease censorious gallery-goers.

His naked portraits of her reveal a woman utterly at home in her body.

In 1911 she painted Joy of Life—a study of four women, who have been bathing and are observed by a naked man (André again). It’s something of a homage to Édouard Manet’s scandalous Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), which depicts two fully clothed men having a picnic with two women, one of whom is naked, the other lightly dressed in a chemise. A year later, Suzanne painted a naked young woman reclining on a red couch, gazing down at another woman kneeling on a carpet, her cards laid out before her. Her nakedness is comfortable, unseductive; the color of her long plaits is echoed in the red of her pubic hair. She is dignified, strong, full of power. The fortune teller holds the queen of diamonds: a card that signifies wealth, authority and wisdom.

The compositions of these high-key, expressive paintings are crammed with details—the grey-blue flowered wallpaper, the burgundy couch, the rich blue-and-orange carpet, the long red hair, the dense green grass: there’s a palpable sense of pleasure in the physical world. Suzanne used herself as a model in each of these paintings. She also modeled for André: his naked portraits of her reveal a woman utterly at home in her body.

At the age of forty-six, in 1911 she had her first solo show at the Galerie du Vingtième Siècle—the Gallery of the Twentieth Century—which was run by a former clown with a good eye, Clovis Sagot. He had been supportive of artists including Picasso and Juan Gris and was enthusiastic about Suzanne’s work. The show didn’t sell well but she was becoming better known.

In Portrait de Famille (Family Portrait), which Suzanne painted at the age of forty-seven, she depicts herself surrounded by two young men and an old woman—all of whom are looking away, as if too absorbed in their thoughts to concede the artist’s presence. To her right is André, who, with the declaration of World War I she would soon marry, in part to get paid as a soldier’s wife. Maurice, who was now achieving some success as an artist himself, is to her left: his dejected pose and despondent expression hint at his problems with mental health and addiction. Behind her is Madeleine, her fierce, bent, elderly mother, who was to die three years later. Only Suzanne, the painter, stares directly out at us, her right hand on her heart. This is my family, she seems to be saying: this is me.

*

Undeterred, at the age of sixty-six, in 1931 Suzanne painted another remarkably frank self-portrait. Against a rough lemon background, a vague glimpse of either a landscape or a painting over her right shoulder, she outlines her body in heavy, fluid lines. As with Paula Modersohn-Becker’s self-portrait, her only decoration is a simple necklace. Her bare breasts droop and her lightly wrinkled face is capped with her smooth dark hair, cropped like a beret. Her thin dark eyebrows hover above her tired blue eyes like the open wings of a blackbird. She looks directly at us: she has nothing to hide.

___________________________________

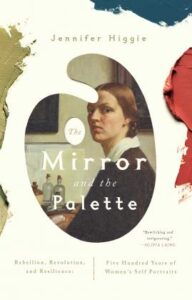

Jennifer Higgie’s The Mirror and the Palette is out now from Pegasus Editions.

Jennifer Higgie

Jennifer Higgie has a B.A. in Fine Art from the Canberra School of Art, and a MA from Victoria College of the Arts, Melbourne; her paintings are in various public and private collections in Australia. Previously the editor of frieze magazine, she is now frieze editor-at-large and the presenter of Bow Down, a podcast about women in art history.