How Someone Else's Writer's Block Helped Me Write My Novel

Robert Siegel on Getting the Details Just Right

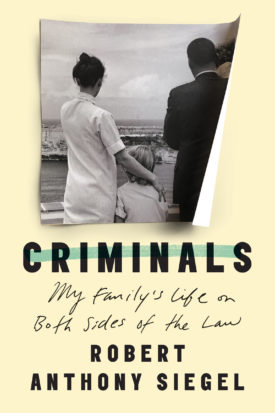

My first novel was about my father, a criminal defense attorney who broke the law and ended up going to jail. I worked on it in secret, in a tangle of grief, love, anger, and guilt so intense I found it almost impossible to write. I would sketch out a scene, feel like a traitor, erase the scene, and then take the subway to my parents’ apartment to make sure my father was still alive, that I hadn’t magically killed him. Usually, I found him in front of the TV, downing antidepressants and eating vast quantities of leftovers. He was having a hard time rejoining society.

That was my problem too, in a way. I’d just finished an MFA and desperately needed a job, but couldn’t find anything. Then a friend got me an interview with a professor of Korean Buddhism, a former Buddhist monk, who was starting a publishing company to produce scholarly books on Korean religions. I didn’t know anything about Korea, but I had spent some years in Japan and was “comfortable” with East Asian cultures—that was my selling point.

The interview took place at a Korean barbecue place deep in Queens. Professor Park and I sat opposite each other, wearing bibs. “Robert,” he said, with a wonderfully formal manner possessed only by foreign speakers who have mastered the language from outside and know it as a thing of elegance and beauty. “I have asked you here today because Korean Religious Studies in America are in the most extreme danger. A new generation of American scholars has completely misunderstood the fundamental nature of Korean Buddhism, and they are spreading their false views throughout the academy. They treat it as if it were a philosophy, a collection of clever ideas, and not a religion. They do not understand that Buddhism is about salvation.” He put down the spare rib in his hands and wiped his fingers on his bib. “Robert, the world needs salvation. But I can’t do it alone—I don’t have the strength.” He pantomimed exhaustion, slumping his shoulders as if under a great weight.

Professor Park looked to be in his early fifties, about the age my father was when he went to jail; maybe that had something to do with the odd protective urge I felt. “I’ll take the job,” I said.

As it turned out, the position was something close to what was once called an amanuensis, a literary secretary. I sat at a little desk next to Professor Park’s big one and wrote elaborate letters for him in his formal style, the sort of ornately polite correspondence not seen since the advent of the telephone. Most of those letters were written for other people, pawns in various schemes he was cooking up to save Korean Religious Studies. We wrote them for the president of the university to use, thanking one or another donor in Korea for their generous support. We wrote letters for those donors to send back to the president, reiterating their belief in the urgency of our mission and hinting at a desire to donate even more, if the university would only increase its support too.

I loved writing those letters. They were fiction, really—pleas for help channeling a little bit of the urgency I felt in my own life but could not name. I would bang them out without hesitation or erasure, temporarily forgetting that I was a failure as a novelist.

“Just don’t be surprised if they talk like they’ve met you already.” He gave an embarrassed little laugh. “Because I pretended I was you.”

When we ran out of letters to write, Professor Park would lean back in his big chair and talk about Buddhism. These weren’t conversations so much as beautiful monologues about the cataclysmic struggle between Great Doubt and Great Faith that leads to enlightenment. I would lean forward in my seat, completely unaware of how the moment recalled other moments, long gone, when I would sit in my father’s law office and watch him entertain clients with stories about the criminal courts and the cases he had won. I’d been too young, back then, to really understand those stories, but had total faith in the message encoded in his voice, which implied that only he knew how to keep us all safe. The more complicated and scary the things he described, the safer I always felt.

As Professor Park talked, the light from the big window behind him would start to drop, turning the room golden and melancholy. I had a sense that he was lonely and didn’t want to go home, and on some level, that was okay with me, because the only thing waiting back at home was my novel, with all its unfinished sentences.

Around this time, Korean Religious Studies faced a crisis: one of our authors, who had been sending us chapters of his book on Confucianism, racing to finish in time for tenure, had suddenly developed writer’s block. “You need to go down there and finish it for him,” Professor Park told me.

“But I can’t do that.” For starters, I wasn’t a scholar of Confucianism—wasn’t a scholar at all. I didn’t know anything.

“If he doesn’t finish it, he won’t get tenure, and if he doesn’t get tenure, he’ll lose his job. We can’t let that happen.”

The next day, I took Amtrak to a little suburban station beyond Washington, D.C., and walked down the stairs to the parking lot, where the Professor was waiting for me: a short, stocky Korean man in a raincoat buttoned to the neck, smoking a pipe. He had a beard but his upper lip was shaved and looked bare and vulnerable. It made him look like an old-time ship’s captain out of Melville, the kind with vast knowledge of scripture and a tragic sense of the future. “Robert Siegel?” he asked gravely.

“That’s me.”

We drove to one of those magically odd subdivisions where a single house has replicated itself everywhere in ever so slightly altered shapes, and thus seems to imply that you are not awake but dreaming. His wife met us at the door, a very small woman dressed in surgical scrubs. She was an operating room nurse who assisted in ocular surgery, and she had the brisk, no nonsense air of someone who handles tiny knives meant for eyeballs. I could tell right away that she was deeply irritated with the professor—irritated that he had fucked up and needed someone to rescue him. As if to drive the point home, she sat me down in the living room and had their little boy play Chopin on the piano. He was maybe ten years old, pear shaped, with a crew cut and complicated, intelligent eyes, and his small chubby fingers flew over the keys.

“Pretty good, no?” she said to me. “Marvelous,” I answered.

“He practices every day.”

The professor seemed to feel their dual judgment acutely, and as a result his expression grew more and more pompous. “Come,” he said to me. “Let me show you where you’ll be staying.” He took me up to the attic, which had been renovated into a guest room. “I have an outline and notes for you to use, and all the English sources I’ve been citing.” He pointed to a folder sitting on a small desk by the bed, and a stack of books on the floor, bristling with post-it notes, and then looked distressed, which for him meant intensely dignified but with an unhinged glint in the eyes. “I thought I could make it to the end, but then something happened. I sat for days, unable to write the next sentence. What do you call that, writer’s block?”

“Yes, writer’s block.” I didn’t like saying the words.

“Not even a single sentence,” he said, sounding bewildered.

The idea of losing everything in the world because you can’t give voice to what’s in your head—it made me angry. I spent the rest of the night going over his notes, and began writing early the next morning. Sitting at the desk, I pictured that grave, pompous, wounded face, and then pretended it was my face, that I was him, and suddenly, without effort, the sentences started to unfurl. This became my pattern. Mornings I would type as fast as I could, using his outline and notes and quotes from the volumes stacked by the desk. Afternoons, he and I would take long walks through the subdivision, discussing the material. Most interesting to me was the Confucian view of language itself, the belief that it was a mystical force with the power to shape reality, something like a magic spell. Use the right words in the right way, and people would become good, families happy.

“What do you think of that?” I asked the professor.

He had his raincoat buttoned up to the neck as he trudged along, smoking his pipe. “They didn’t know about writer’s block back then.”

The midwinter light was falling, turning the street a dark shade of purple. Since the houses all looked more or less the same, we could have walked into any one of them and been home, for all I knew. The result was an inexplicable nostalgia that grew more intense each time we turned a corner. I was longing for home, I realized—not the place I lived now, but the safe-seeming world I’d grown up in before my father went to jail. A world that was gone forever.

“The idea of losing everything in the world because you can’t give voice to what’s in your head—it made me angry.”

It took two weeks to finish the professor’s book. On the day of my departure, his wife and son stood downstairs to say goodbye. I asked the boy to play something and he did, something complicated and fast, a torrent of exquisite notes coming from those tiny fingers. “You’ll miss your train,” said the professor, picking up my bag and carrying it out to the car, his raincoat buttoned to the top, as always. I followed, the music flowing out the door behind me.

Back in New York, my novel started to go a little better. Sitting at the computer at home, I would imagine myself hovering above the ground, almost as if I were still in the professor’s attic, but this time so high up that my characters looked tiny, and their sorrow and stupidity nothing to be afraid of. Then I would imagine that my arms were incredibly long, miles long, reaching all the way down to my keyboard. Typing from so far above, it was almost as if I wasn’t typing at all. I started to finish my sentences, which in turn allowed me to complete pages, then chapters. Soon I found myself making real progress, though I had to look away quickly before the fact of my forward motion sunk in and I was tempted to start erasing.

The trick of placing myself in the professor’s attic worked till I came to the prison chapters. In real life, I’d been living in Japan during that period and only knew what my mother and siblings had described to me: long train trips that started before dawn, followed by a special prison bus full of hard-luck families loaded with crying children.

Once inside, our father would shake them down for money to spend in the vending machines and then refuse to talk to them. Sometimes, he’d fly into a rage; other times, simply walk away… He himself never spoke about jail. If it came up, his face would become agitated and he’d fall silent.

It’s a novel, I told myself. Make it up. But somehow, I just couldn’t. My father’s time in prison was a box full of sorrow so overwhelming it could not be opened, a toxic mixture of all of our vanity, stupidity, pretension, and naiveté. If I were to lift the lid, something unimaginable—by which I mean irrefutably true—would pour out and drown us all.

I must have looked pretty bad, because one day, my father asked me how the book was coming. “My novel?” I asked, growing cautious. I’d told him it was a legal thriller about a lawyer mistaken for a drug lord, hoping that would sound innocuous.

“Yes, how’s it going?”

“Not so good,” I said, and then fell into an old and pointless complaint: what I really needed was an office. If only I had a dedicated space in which to write, I could finish the book in no time.

My father nodded sympathetically. “Hey, listen, don’t be mad, but you’ll probably be getting some calls about office space. I had a free afternoon, so I stopped by a few buildings and talked to the management.”

“And you gave them my number?” It was ridiculous; I didn’t have the extra money to rent one square foot of an office.

“Just don’t be surprised if they talk like they’ve met you already.” He gave an embarrassed little laugh. “Because I pretended I was you.”

“Why did you do that?” All this time, I had been pretending to be the professor so I could write my father’s story, while my father had been walking around town pretending to be me.

“I don’t know.” He looked genuinely perplexed for a moment, and then he said, “Your sister told me that your book has a prison chapter in it, and that you’re stuck.”

Of course, I shouldn’t have been surprised. On some level, I’d always known that he understood the novel was about him. “A prison chapter is just one possibility I’m considering,” I said, feeling my heart begin to throb in my chest. “There are others.”

“Well, I’ve been there and can tell you whatever you need. Ask anything.” His face was composed as he waited. He had clearly thought this moment over, prepared himself. But now that I had my chance, I couldn’t ask anything: the questions were all buried too deep, under too many contradictory feelings.

After a while he said, “Why don’t I just tell you a few details,” and then began with his first night, how they put him in the infirmary because his blood pressure was explosive. He talked about the guards—screws, he called them—and how they strip-searching them for no reason, calling them names, trying to get them to react so they could write them up for an infraction. And yet the biggest problem was not the guards but the boredom. Some inmates kept busy, and others spent the entire time lying on their cots, staring at the ceiling. He got a job mowing the grass, and lost two hundred pounds. It helped that the food in the cafeteria was dreadful, and the vending machines only took coins. If you had cash, the guards would order Chinese takeout for you, for a fee, but he never had any money.

No, the worst thing wasn’t the boredom or the food; it was being locked up. “Did anyone ever try to escape?” It was more a wish than a question. “Nobody. We were all short timers. We just had to sit tight and wait.”

I started to breathe again, slowly. Beyond anything else, it was listening to his voice, the fact that we were talking about the one thing I assumed we could never talk about, and nothing cataclysmic had happened. It turned out that the box I was so frightened of opening contained only ordinary sorrow, the kind I could stand.

“You can use any of that,” my father said. “You have my permission.”

I was unable to speak. The best I could do was to open the sliding door and step out onto the balcony, to let the winter wind freeze me till the panic and the gratitude and the sense of stupidity all subsided. It was too early to wonder what this new kind of novel might look like, or who I would have to become in order to write it. I just wanted to stand there and let the real world swirl around me for a little while.

![]()

From Criminals by Robert Siegel, courtesy Counterpoint. Copyright 2018, Robert Siegel.

Robert Anthony Siegel

Robert Anthony Siegel is the author of two novels, All the Money in the World and All Will Be Revealed. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian, The Paris Review, The Oxford American, and Tin House, among other venues. Robert has been a Fulbright Scholar at Tunghai University in Taiwan and a Mombukagakusho Fellow at the University of Tokyo in Japan. Other awards include O. Henry and Pushcart Prizes and fellowships from the Fine Arts Work Center and the Michener-Copernicus Society.