How Smell—the Most Underrated Sense—Was Overpowered By Our Other Senses

Ashley Ward on the Oft-Ignored and Much-Maligned Olfactory Sense

Despite the wonderful contributions that smell makes to our lives, it’s undervalued in modern Western societies. Polls conducted in both the US and the UK reported that of our five main senses, smell was the one that people were least concerned about losing, while a study of British teenagers found that half would rather be without their sense of smell than their phone.

In 2019, a survey on Twitter asked respondents to rank their senses in order of importance. By now it won’t surprise you to learn that smell trailed in last. Time and again, we exalt vision and hearing to the highest places in our sensory pantheon, but why is it that we regard smell as the sensory poor relation?

It may have to do with olfaction’s checkered past. For much of human history, smells were things to be wary of. The idea that sickness was borne out of noxious smells was the prominent theory in disease propagation for centuries. Clouds of pungency, known as miasmas, released from unclean dwellings, filthy streets, and even the ploughing of soil, were blamed for contaminating the body, leading to any number of maladies. A debilitating fever emerging from marshes and swamps was named after the medieval Italian for bad air: mal’aria. Terrifying epidemics that haunted the world for centuries seemed to be induced by foul, corrupted air.

During the fourteenth century, the bubonic plague outbreak that came to be known as the Black Death claimed thousands of victims, condemning them to a rapid and painful end. As the sufferers deteriorated, the disease tainted them with a tell-tale, repellent stench, which seemed to confirm smell as the root cause of the illness.

We’re not always comfortable with seeing people, especially adults, smell things.Over the ages, medics used various herbs and perfumes to counter the supposedly deadly whiffs. Seventeenth-century physicians wore peculiar head-to-toe costumes, anointed with all kinds of aromatic substances, and featuring a prominent and nightmarish beak-like structure, packed with pot pourri to freshen each intake of breath. Wealthy citizens took to carrying pomanders, containers of pricey aromatics such as musk and sandalwood, around their necks and in doing so raised themselves above not only disease but the stench of the poor.

The less well-to-do improvised by using a lemon for the same purpose. Noisome dwellings were set right by fumigation, while rooms were doused with strong-smelling substances like vinegar and turpentine—anything to keep at bay the dreaded miasma. The idea remained prevalent until the nineteenth century and as late as 1846, the social reformer Edwin Chadwick memorably declared “all smell is disease.”

We only have a vague sense of how the past smelled. Odors are rather more resistant to recording in comparison with photographs, video clips and audio files. We’re largely reliant on descriptions, which is perhaps no bad thing, because in the days before showers and laundries, it’s likely that people and the towns they lived in would be somewhat challenging to a modern nose. However, although bad smells could never be anything other than unpleasant, we tend to perceive the smells that surround us as being normal.

The process of habituation means that continuous stimuli gradually get downgraded, and the brain ignores what amounts to background noise. When we’re on a long-haul flight, the air becomes stale, even with the air-purifying equipment on board. We sit in this stew of gases for hours, scarcely aware of how fetid it is until we disembark. It’s a different matter for the airport staff who open the doors on arrival; they get a gust of plane gas that amounts to the olfactory equivalent of a slap in the face. Taken the other way around, astronauts who’ve spent time in orbit on their return to Earth describe commonplace smells, such as trees and vegetation, as heady, intense and wonderful.

*

While odors themselves were regarded with distrust, it seems like every famous man in history who ever felt moved to write about our sense of smell had some derogatory point to make (there’s a notable shortage of opinions from the women of history). Most fall into one of two camps: those who regarded smell as relatively unimportant, and those who associated it with depravity. Plato considered that smell was linked to “base urges,” while others described it as degenerate and animalistic. Aristotle wrote that “man smells poorly” and Darwin asserted that “the sense of smell is of extremely slight service.”

Freud’s conclusion was that in normal development, any fascination with smells should be left behind in infancy, and he’s far from alone in this judgement. We’re not always comfortable with seeing people, especially adults, smell things; it seems weird to us. My own cousin, Amanda, used to luxuriate in aromas as a child, lifting all manner of things to her nose to experience their scent. The impulse was coached out of her over time by her parents, who always seemed to find it odd.

More broadly, the emphasis on observation that accompanied the Enlightenment in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries placed a premium on vision as a means of verification; the use of the phrase “I see” to mean “I understand” is telling. In this context, sight is a dispassionate means of apprehending the world. Smell, meanwhile, with its fuzziness and links to emotion was relegated to the margins.

Amid the aforementioned cast of olfactory objectors, one man in particular seems to have been particularly influential in shaping our views on the human sense of smell. The nineteenth-century French surgeon and anatomist, Paul Broca, was a pioneer in the quest to understand the brain. In true mad scientist style, Broca kept hundreds of them in his Paris laboratory, preserved in jars of formalin. His fascination was with its different structures and, in particular, the frontal lobe.

Smell was a base, primitive sense, and shedding it was evidence of human superiority.This area, situated right behind the forehead, is critical to all manner of functions, including consciousness, memory formation, empathy and our personalities. Compared to other mammals, primates are blessed with especially large and complex frontal lobes, and among primates, humans emerge as being disproportionately equipped in this area. The goal in these early days of neurology was to relate function to the different parts of the brain and in this initiative Broca was extremely successful. He’s best remembered for his research into the parts of the frontal lobe that govern speech production, which now bear his name: Broca’s area.

Yet even while Broca was advancing his field, he was formulating other ideas that remain influential despite their shortcomings. In effect, he was searching for evidence of human distinctiveness and he considered that he’d found in it his measurement of different species’ brains. He contended that in humans, the olfactory bulb, the part of the brain that receives information from smell receptors, had shrunk to make space for the enlargement of the frontal lobe.

Adding two and two together to make twenty-two, Broca seized upon this as proof of mankind’s elevation above the other animals. The frontal lobe had “grabbed the cerebral hegemony,” he crowed. “It is no longer the sense of smell that guides the animal.” Thus, smell was a base, primitive sense, and shedding it was evidence of human superiority.

In the intervening years, many scientists have followed Broca’s lead and arranged the facts to fit their theory. In reconstructing human evolution from a sensory point of view, it has been claimed that our transition to walking upright took our noses away from the ground and so away from the richest whiffs and pongs. In the process, so it’s been argued, we relegated the importance of olfaction.

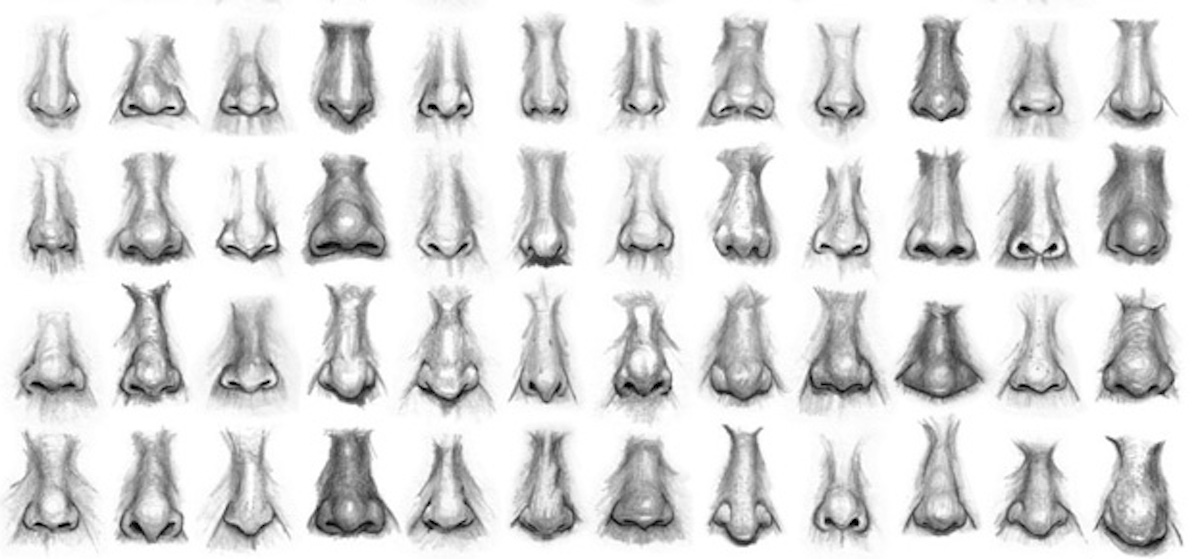

Going back further, the migration of primate eyes to the front of the face allows excellent stereoscopic vision, compared to the side-of-the-head arrangement favored by many other mammals, but limits the space available for the olfactory equipment. The loss of the snout in apes especially seems only to further restrict the capacity for smell.

Finally, primates in general and humans in particular seem to be losing genes associated with our sense of smell. We have something like 400 working olfactory genes, but sitting in our genetic code are close to 500 olfactory pseudogenes. These are the genetic equivalents of fossils; genes that used to contribute to our sense of smell but that no longer work. In other words, we’ve lost over half of our smell genes across evolutionary time.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Where We Meet the World: The Story of the Senses by Ashley Ward. Copyright © 2023. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.