How Sigmund Freud Tried to Break and Remake His Fiancée

"He Wanted Martha to Remember That She Was Nothing Very Special"

When Sigmund Freud and his fiancée Martha Bernays were apart, as they were for most of their four and a half year-long engagement, they corresponded at a rate that would have put any epistolary novelist to shame. Until recently, however, the public has seen only a modest selection of Freud’s engagement letters, primly redacted by his heirs with the aim of forming “a portrait of the man”—a portrait, that is, of a steadily affectionate fiancé, sometimes ill-humored but gradually led by the strength of his love toward greater self-command.

The full archive allows some less complimentary inferences to be drawn. Upon reading the letters, even Freud’s sympathetic biographer Ernest Jones remarked, confidentially, to a trusted ally, “Martha comes out of the letters excellently but Freud was very neurotic!” Jones could see that the state of being engaged had brought out an infantilism in Freud that must have been present all along; and some of his strangest behavior, which Jones noted but passed over as quickly as possible, had occurred toward the end of the long delay.

In the Brautbriefe (engagement letters), we see Freud was already experiencing a problem that he would one day ascribe to all men: an inability, held over from early childhood, to reconcile female sexuality with maternal purity and devotion. His bride was supposed to arrive intact, submissive, and sexually ignorant, but also to reciprocate a lust that he hoped would outlast the honeymoon. Yet she was also expected to coddle him as her indulged son. That role, in Freud’s estimation, was a woman’s highest calling. As he would put it in 1933, “Even a marriage is not made secure until the wife has succeeded in making her husband her child as well and in acting as a mother to him.”

In the same juvenile vein, Freud morosely reminded his fiancée that their ideal happiness couldn’t last for long, because “dangerous rivals soon appear: household and nursery.” He feared that Martha’s everyday wifely tasks, with or without children underfoot, were going to rob him of her full attention.

Because Freud was concerned to protect his fiancée from sexual knowledge, it has been assumed that she must have exemplified the aversion to eroticism that he would later ascribe to virgins in general. The Brautbriefe, however, show us a very different Martha—a coquettish one who allowed herself to be kissed by another man after pledging herself to Freud, and who took pleasure from inflaming her beloved’s desire. In one letter, for example, she recounted a dream in which the two of them held hands, gazed into each other’s eyes, and then “did something more, but I’m not saying what.” Note, too, that this amatory teasing came less than two weeks after the start of the secret engagement.

When he wasn’t complaining about his present ailments and future neglect, the unhappy fiancé was instructing his beloved in how to become a properly deferential mate. He made it clear that she would have to change some of her ways, and the sooner the better. It was precisely Martha’s most admirable qualities—unselfconscious candor and spontaneity, a trusting nature, freedom from class prejudice, loyalty to her family and its values—that struck him as in need of revision. Thus he rebuked her for having pulled up a stocking in public; forbade her to go ice skating if another man were along; demanded that she sever relations with a good friend who had gotten pregnant before marriage; and vowed to crush every vestige of her Orthodox faith and to turn her into a fellow infidel.

The area in which Martha most urgently needed reeducation, Freud believed, was that of excessive regard for her own family. He had coveted its name before their engagement, but now the very illustriousness of Martha’s connections prompted a worry that she and other Bernayses might look down on him as a parvenu. He would try relentlessly, then, to extirpate everything “Bernays” about his fiancée and bride. “From now on,” he admonished her in a falsely jovial decree, “you are only a guest in your family, like a gem that I have pawned and that I am going to redeem [auslösen] as soon as I am rich.”

Likewise, despite the syrupy passages in his Brautbriefe, Sigmund wanted Martha to remember that she herself was nothing very special. Just nine weeks into the engagement, for example, she was informed that her looks were hardly out of the ordinary. (In stressing her sober virtues instead, Sigmund was evidently trying to discourage her from flirting with other men.) And at times he teased her patronizingly about her want of experience and her inability to collaborate in his work. After she had tried to help him with a translation project, he wrote, “I am nothing short of delighted by my little woman’s unskillfulness.”

Sigmund’s excuse for rehearsing Martha’s limitations was that he occasionally performed the same exercise on himself. As he wrote on November 10, 1883, “Since I am violent and passionate with all sorts of devils pent up that cannot emerge, they rumble about inside or else are released against you, you dear one.” The vices he acknowledged were a bad temper, a penchant for hatred—”I can’t hold out against silent savagery”—and “a tyrannical streak” that made “little girls [namely, Martha] afraid of [him]” and rendered him all but unable to “subordinate [him]self” to any other person. In owning up to such traits, however, Freud wasn’t resolving to curb them in his marriage. “You see what a despot I am,” he warned just one month into the engagement. Martha was to understand that the despotism would persist.

The couple’s engagement included no period of romantic comradeship before Martha’s new master began laying down the rules. She was told from the outset that she would be expected to serve his needs, manage his domestic existence, and honor his decisions in all other matters. The doll’s-house diminutives with which he addressed her only reinforced the message that his darling girl was to live only for him, exercising no individual will. As for “feminine” means of gaining advantage, he declared that they wouldn’t be tolerated. “I will let you rule [the household] as much as you wish,” he decreed, “and you will reward me with your intimate love and by rising above all those weaknesses that make for a contemptuous judgment of women.”

Although Freud was echoing the separate-spheres ideology of his era, he did so in awareness of more liberal views that were beginning to attract serious notice. Indeed, in 1880 he himself had translated into German, as an assignment for a fee, a volume of John Stuart Mill’s works that contained the century’s most stirring plea for gender equality, The Subjection of Women. There he encountered a passionate argument against the oppressive attitudes and customs that had spared European males from having to vie academically, professionally, and politically with 50 percent of their contemporaries.

To Freud’s way of thinking, Mill’s position was nonsense. “For example,” he reported to Martha in bafflement, the author “finds an analogy for the oppression of women in that of the Negro. Any girl, even without a vote and legal rights, whose hand is kissed by a man willing to risk everything for her love could have put him right about this.” And he added,

It is also a quite unworkable idea to send women into the struggle for existence in just the same way as men. Should I think of my delicate, dear girl as a competitor? The encounter could only end by my telling her, as I did seventeen months ago, that I love her, and that I will make every effort to get her out of the competition and into the unimpeded, quiet activity of my house. . . .

No, here I stand with the elders. . . . The position of woman cannot be other than what it is: to be an adored sweetheart in youth and a beloved wife in maturity.

Freud didn’t ask his fiancée whether she agreed with those sentiments. Her expression of a contrary opinion would not have counted—except, of course, as a sign that she was not yet reconciled to her destined role. As Ernest Jones observed with unusual bravery, Freud was insisting on nothing less than “complete identification with himself, his opinions, his feelings and his intentions. She was not really his unless he could perceive his ‘stamp’ on her.” And again, the relationship “must be quite perfect; the slightest blur was not to be tolerated. At times it seemed as if his goal was fusion rather than union.”

This zeal to remake another personality doesn’t look promising for a career in psychotherapy, a field that relies on empathy with the traits of others. As is well known, Freud would remain puzzled by women but would cover his ignorance with dogma about a biological inferiority that causes all of them to remain childish, envious, and devious. That hurtful doctrine would be rooted not in clinical findings but in prejudices and fears that the theorist had manifested long before aspiring to expertise about the mind.

__________________________________

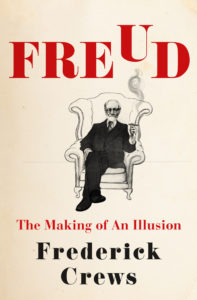

From Freud: The Making of an Illusion. Used with permission of Henry Holt and Co. Copyright © 2017 by Frederick Crews.

From Freud: The Making of an Illusion. Used with permission of Henry Holt and Co. Copyright © 2017 by Frederick Crews.

Frederick Crews

Frederick Crews is the author of many books, including the bestselling satire The Pooh Perplex and Follies of the Wise, which was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle award. He is also a professor emeritus of English at the University of California, Berkeley, a longtime contributor to The New York Review of Books, and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.