How Shirley Hughes Captured the Everyday Magic of Childhood

Ellen O'Connell Whittet on the Beloved Children's Author

Every morning, when my one-year-old daughter pulls on her pink rain boots to go in the backyard, she tells me, “Like Alfie.” Last week at the grocery store, she asked if we could get a bouquet of flowers for Granny for her birthday, which is in five months, like Lucy buys for her grandmother.

She’s imitating two of her favorite children’s book characters, each, along with their siblings, protagonists in a series by British author Shirley Hughes, who died on February 25 at age 94. Two sets of siblings—Lucy and Tom and Alfie and Annie Rose—go with my daughter in the car or to the doctor’s office, much like other kids bring their lovies for quick comfort. The books she pores over are stained with my own jammy thumbprints and scribbled on by my brother. They are the first books I read to her when she was born and the ones I hope she passes down, too. They are books in which nothing and everything happens at once, and children are in constant motion, just like my toddler. Alfie might leave a beloved stuffed elephant on the bus, or the cat might have kittens. Grandma might bake cookies and let the children use the cookie cutter. It might rain, but when it clears up, everyone will put on their rainboots and go out for a walk.

Shirley Hughes wrote over 50 books and illustrated some 200 with pen and ink, gouache, and watercolor. Her scenes are quintessentially English. They feature unsentimental dramas that elevate both the mundanity and tiny crises of childhood. In Lucy and Tom’s ABCs, one of the books that travels with my daughter, “I is for ill,” which is exceedingly tedious, and Tom calls out for other people to come to his bedside to entertain him. In Alfie at Nursery School, Annie Rose is too young to go to school with her older brother which upsets her every morning at drop off, until she decides to join him onstage in the summer concert. But alongside these sorts of dramas, Hughes captures the everyday magic of a child’s earliest years.

Hughes’s own childhood was spent in a small English town during World War II, where she got lots of inspiration for her books, including a cat who often went missing, breaking her heart each time before returning home. Ideas came to her even amid rationing and air raids. When the GIs arrived in Liverpool, she got her hands on American comics for the first time, just as she was just starting to seriously consider art in her late teens. “A tremendous influence on me, of course, were comics,” she said. “You learn about line [from comics], but most of all you learn about telling a story, which is what I’m doing in a different sort of way.”

There is no fantasy in Hughes’s stories, only the excitement of discovery.

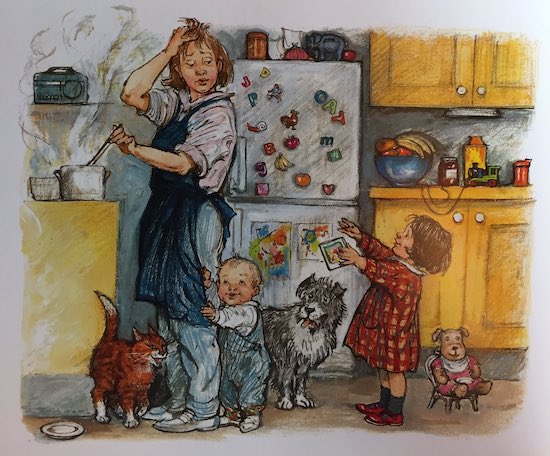

Hughes studied life drawing at Ruskin College of Drawing and Fine Art in Oxford. She began illustrating as she raised three children of her own in the Notting Hill neighborhood of West London, where she frequently allowed interviewers to film her working at home, squeezing out her tubes of gouache and setting to work on the “terrible battles of very serious things” children face, like “getting your shoes on the right feet, going to a birthday party without your security blanket… it’s very important to a small child.”

It is precisely the way Hughes’s illustrations honor the children at the center of her books that makes them so remarkable. “You go out into the park and there are all these children playing,” she told BBC in a 2017 documentary filmed largely in her home. “Their gestures—it isn’t just their face—it’s the way they all crouch down together when they’re looking at something very intently and then they all jump up and run off like a flock of starlings. And the way they stand when they’re rather unsure of themselves. The way their feet go when they’re a bit nervous, and then they’re wildly joyous and flinging themselves into the air. Oh, it’s lovely.”

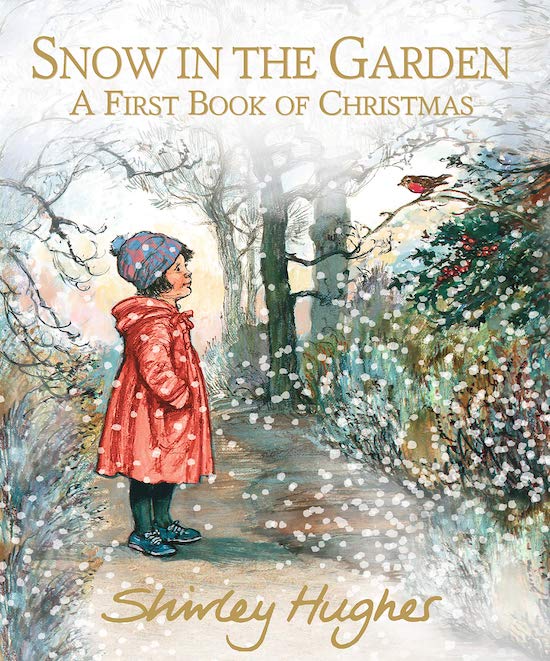

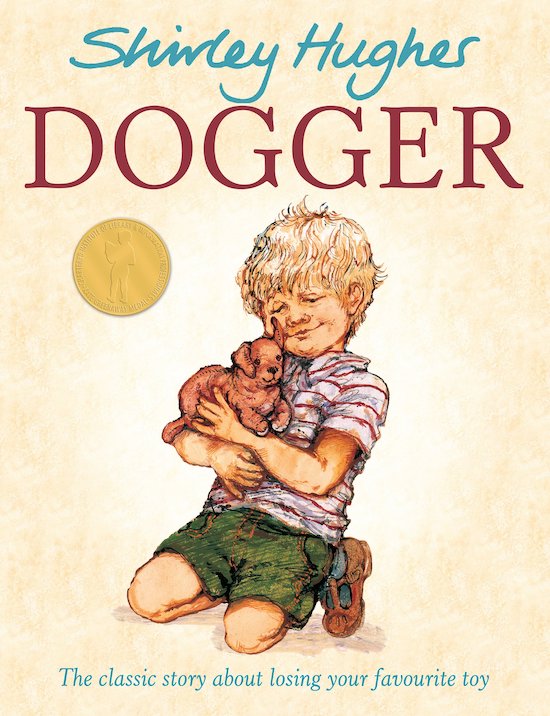

There is no fantasy in Hughes’s stories, only the excitement of discovery. No one can fly or shapeshift, but they can turn on the Christmas tree lights for the first time or get a new pair of rainboots and figure out which boot goes on which foot. The stories are low stakes and include scenes straight out of real life that utterly absorb children. In An Evening at Alfie’s,a pipe bursts when a babysitter is there. In Dogger, which won a Kate Greenaway medal when it was first published in 1977 and was later voted Britain’s favorite picture book in a 2007 poll, a little boy loses and then finds his beloved stuffed animal.

The victories are the daily conflicts that can turn a family inside out but rarely make for a compelling story later in an adult world. But for children, especially preschool-aged children like my daughter, these stories teach them everything about the world’s order. She knows that every morning, she must put on her shirt, and it comforts her to know Alfie does the same thing. She recognizes, in life and art, the familiar rhythm of playing and running boring errands with her mother and going to school and celebrating birthdays.

Hughes’s does not put moral lessons at the center of her work except for, on occasion, a plug for kindness. They are more day-in-the-life than they are adventures, because everything, according to Hughes’s books, can be an adventure. And everything is worth our attention. “I want children to learn how to look, how to linger over a picture, and not rush through, flicking from page to page,” she explained to the BBC. “They have a lot to cope with in terms of having to be quick reactors. And I think the enjoyment of art … [comes from] looking carefully, and looking as long as you like.”

Hughes’s books have sold 11 million copies and are beloved in the UK, but they are largely unknown in the United States. My own family discovered them during two years we spent living in London when I was a child, and I try, with the zeal of an evangelist, to give them to all my friends’ children so that they might be absorbed by the detailed illustrations (the Washington Post called Hughes “the Rubens of children’s illustrators”) and active scenes of playgrounds, or the stories about children’s tricycle politics of the block they live on. The children in Hughes’s book are never still—apparently, Hughes sketched neighborhood children almost as quickly as she saw them. “I lurk about in parks and play areas with a sketchbook and observe what I see,” she told The Guardian in 2017.

Hughes leaves behind her a body of work that reminds her readers of children’s real world-agency at the heart of her stories.

Their shoelaces are untied, their stuffed animals are missing an ear, their school bags are flying as they come out of the gate to their waiting siblings. But their material worlds—illustrated with such detail—are bursting with action, too. There is no blond wood or white carpet in their houses. Their shoes are kicked under furniture and the cat is eating up whatever the baby has dropped from the high chair. Bella, the older sister in Dogger, sleeps with seven teddy bears in her bed, and Lucy in the Lucy and Tom series keeps books under her pillow when she goes to bed, “just in case.” Families are kind to one another, even if siblings squabble. At the end of each story, everyone gathers for tea and a biscuit.

Hughes treats children as serious subjects, their concerns and interests integral to a family’s rhythms. There are important disappointments and losses alongside surprises and discoveries. Hughes’s insistence on the primacy of children’s emotions—even and especially their most illogical ones—are her legacy.

I get tired of reading lots of books to my daughter, but I will never tire of reading Shirley Hughes’s books to her. I see my daughter in the pages, but I also see a long-forgotten version of myself. Hughes leaves behind her a body of work that reminds her readers of children’s real world-agency at the heart of her stories. She also reminds me to look closer, more carefully, and as long as I like.

Ellen O'Connell Whittet

Ellen O’Connell Whittet is the author of What You Become in Flight (Melville House 2020), a memoir of ballet and injury. Her writing has appeared in Buzzfeed, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, Vulture, and elsewhere. She teaches writing at UC Santa Barbara. You can find her on Twitter at @oconnellwhittet.