How Scientific and Technological Breakthroughs Created a New Kind of Fiction

Joshua Glenn Chronicles the Development of Sci-Fi in the Early 20th Century

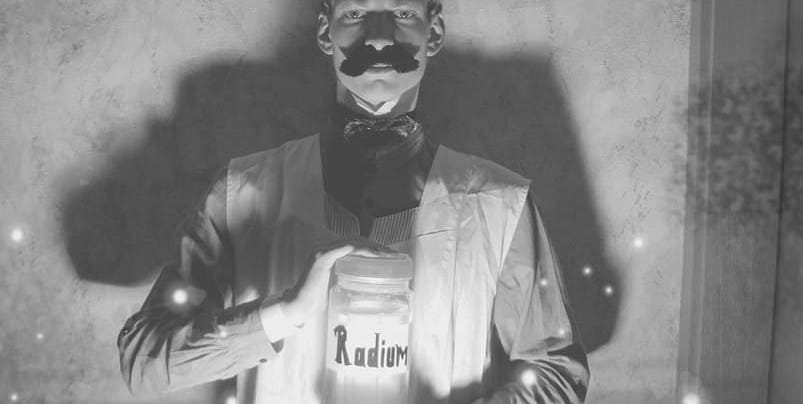

During the early twentieth century, the world’s scientists were wonderstruck by the revelation that the spontaneous disintegration of atoms (previously assumed to be indivisible and unchangeable) produces powerfully energetic “radio-active” emissions. Time, space, substance, our understanding of reality itself were called into question. “The man of science must have been sleepy indeed,” as the author of The Education of Henry Adams would recall, “who did not jump from his chair like a scared dog when, in 1898, Mme. Curie threw on his desk the metaphysical bomb she called radium.”

What Frederick Soddy, the English radiochemist whose lectures would inspire H. G. Wells to predict the atomic bomb, described as the “ultra-potentialities” of radioactive elements seemed limitless. Throughout the nineteen-aughts and -tens, scientists and snake-oil salesmen alike would ascribe to radium—and radiation in general—vitalizing, even life-giving powers. By the 1920s, then, the Soviet biochemist Alexander Oparin and the English biologist J. B. S. Haldane could independently propose that radiation, acting upon our planet’s inorganic compounds billions of years ago, had produced a primordial “soup” from which emerged life.

Science fiction, too, emerged during the genre’s 1900–1935 Radium Age from out of a hot dilute soup of sorts, this one composed of outré genres of literature—from occult mysteries and paranormal thrillers to Yukon adventures and Symbolist poetry—acted upon by the energy of new scientific and technological theories and breakthroughs.

*

George C. Wallis first began writing scientific romances—a trilogy set in Atlantis, for example, as well as a riposte to Wells’s The War of the Worlds in which Martians rescue Earth from meteors—during the late Victorian era. He’d continue writing sf right up into the genre’s so-called Golden Age; his final novel would appear in 1948, a prolific half a century later.

Wallis’s “The Last Days of Earth: Being the Story of the Launching of the ‘Red Sphere’” (July 1901, in The Harmsworth Magazine) is another Wellsian yarn—this one reminiscent of The Time Machine. Some thirteen million years in the future we find Alwyn and Celia, humankind’s designated survivors, channel-surfing between real-world scenes of frozen desolation. Sensitive readers may feel creeping into their bones an intimation of the decentering concept, first articulated by the geologist James Hutton and more recently dubbed “Deep Time,” that human civilization is fleetingly ephemeral in comparison with the literally glacial workings of nature.

Although there are futuristic gadgets here, from a worldwide Pictorial Telegraph relying on “reflected Marconi waves” to the titular planetary escape pod itself, this is no gung-ho tale of tech wizardry. Wallis’s characters feel “the concentration and culmination of the woes and fears of the ages”; those of us aware, say, that the prospect of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius may soon be out of reach can relate to the story’s enervating atmosphere. Which is why the story’s surprise twist, valorizing passion and “an heretical turn of mind,” feels oddly hopeful.

*

Speaking of Wells, one of the prolific author’s finest tales from this era predicts battle tanks—which wouldn’t be deployed in the real world until the Battle of the Somme in 1916. “The Land Ironclads” (December 1903, in The Strand) depicts the defeat of a European country’s military at the hands of a technologically advanced foe. It’s the same plot as The War of the Worlds, really, only instead of Martians the invaders in armored fighting vehicles are fellow Europeans.

The correspondent through whose eyes we witness these events is conflicted. He deplores the “rowdy-dowdy” types who serve as his country’s soldiery…yet when they are slaughtered by button-pushing clerks (“slender young men in blue pajamas,” who may remind today’s readers of drone jockeys fighting videogame-like telewars from the comfort of American suburbs), our man in the field inveighs against these “smart degenerates.” Even as he spouts what Adorno would call the jargon of authenticity, however, he recognizes that war has become pointless.

Via subsequent Radium Age SF novels, including The War in the Air, which depicts German zeppelins devastating New York City, and The World Set Free, which hypothesizes the development of the most destructive weapon the world will ever see, Wells would urgently continue to make the case that there are—in the words of his correspondent—“other things in life better worth having than proficiency in war.”

*

“The Republic of the Southern Cross,” which appeared in Valery Bryusov’s 1907 collection Zemnaya Os (Earth’s Axis), and which was translated into English in 1918, is an account of the fate of Zvezdny (Star City), domed capital of a workers’ utopia situated atop the South Pole.

A decade before Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian We, which explores similar themes, Bryusov asks us to imagine a society in which efficiency has been extended into all spheres of life. The city’s temperature and light are regulated, and “the life of the citizens was standardized even to the most minute details.” Small wonder, then, that a “psychical distemper” should influence the city’s residents to do the opposite of whatever is efficient and reasonable. Hilarity, which soon gives way to gruesomely depicted carnage, ensues.

Like other Symbolist poets who dabbled in proto-sf writing, Bryusov, a leader of the Russian Symbolist movement, was fascinated with the notion that “the days shall come of final desolation”—to quote one of his poems. “We are weary of conventional forms of society, conventional forms of morality, the very means of perception, everything that comes from outside,” he’d announced in 1903. “It is becoming clearer and clearer that if what we see is all that there is in the world, then there is nothing worth living for.” This could serve as a fitting epitaph for Star City.

*

E. Nesbit, the English author known today for Five Children and It and other wry, intelligent contemporary fantasies that paved the way for future fantasists from C. S. Lewis to J. K. Rowling, was a friend of H. G. Wells and a prolific writer of horror stories, some of them sf-inflected. Published under her frequent pseudonym E. Bland, Nesbit’s “The Third Drug” (February 1908, in The Strand) is an early example of proto-sf horror.

Body-snatched and confined by a mad scientist, our protagonist, Roger, is injected with two drugs. It is via the third drug, the scientist claims, “that life—splendid, superhuman life—is found.” Indeed, upon receiving his booster shot Roger does appear to develop unnatural strength, not to mention a sensation of omniscience. Pre-dating J. D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder by a year, and other intelligence-oriented superman stories (John Taine’s Seeds of Life, say, or Olaf Stapledon’s Last Men in London) by over two decades, this is literally heady stuff.

It’s worth noting that Roger isn’t much less scornful of his fellow man than is his kidnapper: During the struggle with Parisian apaches that precedes his capture, he is disgusted by their “pale, degenerate” faces and their subhuman odor. In the end, however, he discovers that “the old common sense that guides an ordinary man” trumps even a superman’s “consciousness of illimitable wisdom” …and that humanity inheres within even a hooligan’s heart.

*

If Bryusov wished to revolutionize our means of perception, then “A Victim of Higher Space” (December 1914, in The Occult Review), by the English “weird fiction” pioneer Algernon Blackwood, warns those of us who share this goal to be wary. In this sequel to the author’s 1908 collection of stories about occult detective John Silence, a psychonaut named Mudge who has been meditating upon a four-dimensional cube diagram seeks Silence’s counsel—because he has slipped into a space-time of infinite dimensions!

The John Silence stories sit at the nexus of what sf historian Paul March-Russell has described as this era’s “mesh of mathematics and mysticism.” Like other weird fiction authors, Blackwood was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a society devoted to the semi-scientific study and practices of the occult, metaphysics, and the paranormal. Paranormal researchers of the era were enthralled by theories of higher-dimensional spaces which, since the 1880s, had been promulgated by the eminent mathematician Charles Howard Hinton—who urged dimension-curious seekers to develop their intuitive perception of hyperspace.

Blackwood’s stories offer us a visceral sense of the appeal of a research methodology that can marry the thrill of scientific discovery with the irrational awe vouchsafed by a vision (like poor Mudge’s) of “a monstrous world, so utterly different to all we know and see that I cannot even hint at the nature of the sights and objects and beings in it.”

*

One of the most popular authors of weird fiction in the United States—“different stories,” per pulp magazine editors at the time—was Abraham Merritt, who wrote as A. Merritt. His sf-inflected novels of the era, including The Moon Pool (1918) and The Face in the Abyss (1923), suggested that alien races and ancient technologies were to be discovered beneath the surface of everyday life— literally beneath the surface, as the explorer Stanton discovers, to his horror, in “The People of the Pit” (January 5, 1918, in All-Story Weekly).

Stanton recounts his sojourn in an underground Alaskan city inhabited by fiends “like the ghosts of inconceivably monstrous slugs.” A canyon is so deep, we read, that it’s “like peeping over the edge of a cleft world down into the infinity where the planets roll!” Describing altar-carvings, Stanton insists that “the human eye cannot grasp them any more than it can grasp the shapes that haunt the fourth dimension.” If this language reminds you of H. P. Lovecraft’s, the story was in fact a key influence on At the Mountains of Madness and other Lovecraft efforts.

By today’s standards, as the Golden Age sf author Jack Williamson, who got his start during the Radium Age, would recall years later, “the kind of style Merritt was creating seems excessive, florid and adjective-laden.” However, as Williamson goes on to insist, Merritt’s proto-sf stories—which hinted at cosmic horror beyond our ken—will reward today’s sf readers’ attention, thanks to their “emphasis on color, wonder, the magic of sheer imagination.”

*

In George Allan England’s “The Thing from—’Outside’,” a creature that may hail not merely from off-world but from a dimension “outside the universe” stalks an expedition in the Canadian wilderness. A science-fictional updating of Blackwood’s 1910 horror tale “The Wendigo,” the story appeared in the April 1923 issue of Hugo Gernsback’s magazine Science and Invention.

England, a popular American pulp fiction writer best known for his (racist) Darkness and Dawn trilogy, creates here an atmosphere of stifling paranoia. Jandron, a geologist, feels a “gnawing at the base of his brain”; members of the expedition begin to perceive reality as though through a glass darkly; they quarrel and turn on one another. All of which may remind John Carpenter fans of The Thing. Which would make perfect sense, since Carpenter’s 1982 movie, set in Antarctica, is an adaptation of Golden Age sf writer and editor John W. Campbell’s 1938 story “Who Goes There?”—which was influenced by “The Thing from—’Outside’.”

Time, space, substance, our understanding of reality itself were called into question.At one point, Jandron name-checks Charles Fort, the eccentric American researcher and author who in works like 1919’s The Book of the Damned presented readers with anomalous phenomena, criticized scientific dogmatism, and proposed (semi-humorous) theories about alien astronauts and the like. “If you knew more,” Jandron chastises his companions, whose refusal to consider Fortean theories he considers narrow-minded, “you’d know a devilish sight less.” This pronunciamento could be a slogan for the many proto-sf stories influenced by Fort’s writings.

*

A modernist poet, novelist, and critic who published as May Sinclair, Mary Amelia St. Clair is best remembered for semi-autobiographical novels such as 1922’s The Life and Death of Harritt Frean. However, she also published supernatural and proto-sf fiction in which mysticism, spirituality, psychoanalysis, and idealist philosophy were intermingled.

Playfully exploring the metaphysical and moral implications of Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity, as well as the hyperspatial theories of scientists and psychi-al researchers, Sinclair’s “The Finding of the Absolute” (1923, in the author’s collection Uncanny Stories) follows the afterlife adventures of Mr. Spalding, a narrow-minded Kantian philosopher who is shocked to discover that his adulterous wife and her lover have been granted entrance to Heaven. But his 3D worldview and value system, the spirit of Kant himself explains to him, is inadequate…because the universe operates on the rules of four-dimensional reality.

One of the first critics to use the phrase “stream of consciousness” in a literary context, Sinclair takes us on a joy-ride through “an unseen web, intensely vibrating, stretched through all space and all time.” The ecstatic flip side of Mr. Mudge’s nightmare, Mr. Spalding’s vision is of a multidimensional reality “utterly plastic to our imagination and our will.” Small wonder that T. S. Eliot and Jorge Luis Borges would sing the praises of the still-underappreciated Sinclair.

*

The final story I’ll mention here is the sole sf effort by an author who twice won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction; in fact, during his lifetime Booth Tarkington was considered America’s greatest living author. If he is mostly forgotten today, it is because—like the reactionary protagonist of his 1918 novel The Magnificent Ambersons—he was fixated on the negative consequences of progress, which may help us puzzle out the meaning of “The Veiled Feminists of Atlantis” (March 1926, in Forum).

Written not long after the 19th Amendment guaranteed American women the right to vote, Tarkington’s satire reimagines the legend of Atlantis’s demise as a war between the sexes. Having agitated for the opportunity to learn the menfolk’s “magic”—which is to say, technology sufficiently advanced to be indistinguishable from magic—the women of Atlantis achieve not only social, economic, and political equality but predominance…at which point they willingly re-adopt the veils that, during their campaign for equality, they’d cast off. Outraged at their own loss of status and power (much like today’s white nationalists), Atlantis’s menfolk revolt.

The sf historian Sam Moskowitz would anthologize Tarkington’s story in a 1972 collection, When Women Rule—thus suggesting that it predicts and celebrates women’s liberation. Writing in a 1980 issue of Science Fiction Studies, though, New Wave sf author Joanna Russ would disagree. “One discerns the familiar charges,” she writes: “that the rule of women over men is unjust (but the rule of men over women was benevolent), and that women’s use of power will be immoral and destructive.” Readers can make up their own minds.

*

Tarkington’s fable, as well as the other proto-sf stories and novels that we’ll reissue via MIT Press’s Radium Age series, can spark lively intellectual debate…and send us on mind-bending voyages into the dimension of imagination. So be careful when reading them! They’re practically vibrating with unknown energies and spine-tingling ultra-potentialities.

__________________________________

Excerpted from More Voices from the Radium Age, edited by Joshua Glenn. Copyright © 2023. Available from MIT Press.