How Ru Paul Created a Castle for Queer Beauty

Sasha Velour on Disguises, Reveals, and Reality TV

Everyone is in some kind of drag. Wasn’t it RuPaul who said, “You are born naked and the rest is drag”? Or as the Bard, William Shakespeare (or one of his ghostwriters), famously wrote, “All the world’s a stage and everyone upon it is just a cross-dresser,” or something like that? Drag holds up a mirror to the performativity of every single person. I don’t think any of us is ever “just being ourselves”—we are constantly putting on an idea of who we are, posturing and pretending for others and even ourselves to the point that it almost seems useless to pin down what’s “real.”

But for many of us who do drag, what we wear isn’t a metaphor. Drag gives us the opportunity to create crucial realities beyond gender, ones that may not be able to be fulfilled offstage. For some, drag is about expressing our true selves. For others, it’s about embodying heritage and ancestry or our own ideas of beauty and ugliness.

For others still, it’s just about being shocking, raising our voices, or having fun! No matter the inspiration or theme, in drag you cannot separate the art from the artist—it takes place on the stage of our bodies. Drag is a demonstration of the infinite flexibility of our imaginations, and a declaration that what we do with our bodies is ours to decide.

When I was growing up in the 1990s, drag as a metaphor was on sale everywhere. Madonna was popularizing voguing around the world as a symbol of modern life, and Calvin Klein and Paper magazine were using imagery of the Club Kids—New York’s post-Warhol, gender-bending, nightlife set—to sell city-themed T-shirts to the suburbs … even as some of the very people who created the artwork were sick or dying from AIDS. Although queerness was becoming legally decriminalized in America, many straight people were still fearful of being around anyone who even looked gay.

But they still wanted to consume our culture. In TV shows and films, queer stories were stolen and portrayed by actors; our signature makeup got mopped by beauty brands to sell products; our catchphrases entered common slang and advertising; our gender-pushing fashions sashayed their ways onto the runway and into the marketplace. Yet only a few queer individuals from the 1990s and early 2000s ever attained “fame” or even cult status among mainstream viewers. Queer ideas became more famous than any queer person.

RuPaul is one of the few icons who got a mainstream spotlight during the 1990s, perhaps because she specifically set out to tap into the mainstream obsession with queer culture and work it for her own advantage. She cited Madonna and Princess Diana as her mentors in the art of media manipulation. Purposefully weaving together several different strains of drag—“Female impersonator” mixed with Club Kid, a dash of 1990s ball culture, and a pageant wig—RuPaul shaped herself into her own version of superstar.

I first saw RuPaul on an episode of Sister, Sister with Tia and Tamera Mowry. I still hadn’t learned the word “drag,” and I thought Ru was just a beautiful giant woman. Yet a part of me still knew there was something special about her, an “Amazonian” woman with unstoppable charm.

I practiced my runway walk in the same bathroom where my partner Johnny and I had filmed my audition tape on a cell phone.Drag reflects society’s most pervasive fantasies, and Ru is undoubtedly the embodiment of classic beauty. But for so many of us queer kids, she also broke the mold by forging success and visibility in a way that hadn’t been seen in our lifetimes—someone beyond gender, and still thriving! Without RuPaul, drag would not look like this today. It is because of her achievements that I myself have had some huge opportunities … even the possibility of writing this book.

RuPaul’s Drag Race first appeared in the early 2000s (and it’s still running strong). As the story goes, RuPaul’s longtime collaborators Tom Campbell, Fenton Bailey, and Randy Barbato pitched her the idea of making a drag parody of reality TV competitions like America’s Next Top Model. Ru’s only concern: to make sure the show was campy and funny but not mean-spirited or mocking. It worked!

Today, Drag Race has become the most successful mainstream media crossover from queer culture … probably of all time. It has given opportunities to hundreds of drag artists from all across the world to show off their talents and share their voices. With franchises in over ten countries, Drag Race has positioned itself as the go-to source for drag queens in pop culture. Queen by queen, Ru literally built herself a drag empire (funny, we keep coming back to imperialism)!

I watched the first season of Drag Race in rapture while I was living in Moscow in 2009 on a Fulbright research scholarship. I routed the episodes through illegal torrents and gagged over BeBe Zahara Benet, Ongina, Nina Flowers, and, later, Raven and Raja. I was 21 and loved reality shows. I recommended Drag Race to everyone I met; I wanted to see it take over!

Although I had never stopped dressing in drag for myself, I didn’t fully understand how vastly drag could change my life, and how this art in particular could reach so many people. Drag Race has continued to shift my life and unravel preconceptions.

Seven years later I got a call from executive producer Mandy Salangsang that I had been accepted into the cast of Season 9 …. My hands were trembling with excitement and I was speechless. “Are you serious?” I asked and later whispered an emotional “thank you” before hanging up the phone to begin planning my costumes. I practiced my runway walk in the same bathroom where my partner Johnny and I had filmed my audition tape on a cell phone—back and forth between the window and the wall under the glow of a Home Depot clip lamp. I was determined to make an impression with whatever I had.

I had so much I wanted to share with the world, and planned to use every opportunity to my full advantage, against all odds. I tried to channel any voices rooting for my downfall (including those in my own head) into a passion and intensity that couldn’t be stopped. You just can’t keep a good queen down, I told myself, and staring into that chipped and paint-stained bathroom mirror, I vowed to keep coming back, no matter what.

I think some people are simply called to put on drag—to inhabit the world between genders, the worlds between the past, present, and future.In 2017, at the start of the most conservative presidency in recent American history, the ninth season of RuPaul’s Drag Race broke all previous records for viewership by transferring to VH1. It was an undeniable hit. Audiences at drag shows grew so large that they broke records for attendance. RuPaul’s DragCon, a convention dedicated to the show and the queens, sold more than twenty thousand tickets in 2019 alone. And there I was, right in the middle of it, terrified and loving it.

Since then, of course, there have been countless spin-off shows, competing drag competitions, lots of merchandise for sale, and more drag performers than ever. Perhaps aided by the fandom surrounding RuPaul’s Drag Race, but also the ease of sharing our art on social media platforms, drag has reached a cultural visibility unlike any other time in history. Drag is the moment!

Unfortunately, while there may be more mainstream interest in drag and more queer representation in the media than ever, many of the people behind the art forms and the real communities we live in are still locked in the fight for equal human rights. Gender expression and sexual identity are not legally protected against discrimination, even here in the US, and many queer and trans people worldwide, particularly trans women of color, experience disproportionate violence and poverty.

And drag, while popular, still doesn’t have the same knowledge and research around it as any other art. I once went to an academic lecture about drag where the speakers’ only primary sources were episodes of RuPaul’s Drag Race. No offense, but we can’t base our entire understanding of drag around one TV show! While inspiring, the very premise of a reality TV competition is still that we drag queens are infinitely replaceable and disposable.

While Drag Race has done so much for queer visibility, I think that local drag scenes abound with queer interventions that deserve our attention too. Bushwig in Brooklyn showcases all genders and styles of drag performance in their yearly festival; Dragula, created by the Boulet Brothers in Los Angeles, is a horror drag competition; Switch n’ Play in New York places focus on queer women, nonbinary, and trans performers; and more. Local shows often partner with community organizations to raise money for queer and trans people in need, and to support legal battles for equality.

Time and time again it is the local scenes that have uplifted our culture and expanded global knowledge of queer history beyond the Western canon. The drag artists of Beirut, Lebanon, introduced me to local icons like Bassem Feghali, who appeared in drag on TV with musical impersonations and comedy for decades. South African queen Belinda Qaqamba Ka-Fassie introduced many to Xhosa drag for the first time. I admire any show or performer who tries to push up against the boundaries of what the “mainstreams” are willing to show, and force us all to reevaluate what our culture includes. That, to me, is the mission of drag!

As alternative styles of drag have grown more popular in local scenes, of course, network shows have tried to adapt and repackage those ideas for mass audiences. No one wants to seem behind the times. But in many ways, the best, most-innovative drag will always be a little obscure, outside of the center, just on the verge of being in fashion.

Don’t get me wrong: auditioning for Drag Race was still the best decision of my life. I do not take for granted the opportunity they gave me to show myself and my work to such a large audience. And I’ll never forget what they taught me: how to market and edit my drag in a self-aware way to make it “pop,” how to win people over with “smoke and mirrors,” and just how many hard-working people it takes behind the scenes to run an empire!

As a result, I have brought my drag around the world, even selling out shows at the Folies Bergères in Paris, The Palladium in London, and The Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco. I always believed in some small way that my art was good enough, that it deserved to exist and be seen. All I needed was the audience, some lights, and a little magic . . .

In the years I’ve spent researching the swinging pendulum of drag’s sometimes popularity and sometimes marginalization, I’ve come to believe that drag will always exist, and that it will always push against binaries. I think some people are simply called to put on drag—to inhabit the world between genders, the worlds between the past, present, and future. Others just want a chance in the spotlight, to show as fully as possible who we are and how we can be. Whatever the reason: give us a stage and a little love, and we’ll put on one hell of a show for you! (No seriously … just give me a stage!)

__________________________________

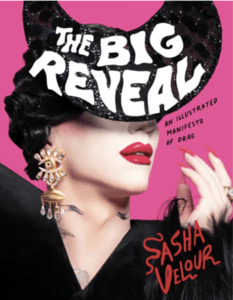

From The Big Reveal. Used with the permission of the publisher, Harpers. Copyright © 2023 by Sasha Velour.