How Robert Crumb Channeled Mid-Century Teenage Angst Into Art

Dan Nadel on the Formative Awkward Adolescence of an Iconic American Cartoonist

Elvis Presley was on the air, Allen Ginsberg was diagnosing the country, and the “sick” comedy of Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Jonathan Winters, and Stan Freberg was rising. Unlike the reassuring jokes of, say, Bob Hope, these comedians peeled back the American skull to reveal confusion about sex, psychology, authority, technology, and industry. Rather than offering a hearty laugh to take the blues away, they wanted to poke the country’s sore spots to provoke conversation and perhaps a bit of social change.

Jules Feiffer’s comic strip Sick, Sick, Sick, published in the just-founded Village Voice, was the comic strip equivalent—his calligraphic lines delineated vignettes of contemporary relationships—embodying themes related to uncertainty, ambition, companionship, sex, and trust. As Feiffer remembered it, “America was unprepared for this sudden onslaught of doubt, insecurity, neurosis. It was unarmed against the guerrilla attack on its own psyche. Confused and on the defensive, WASP America, having begun to lose faith in its own mythic identity, looked around and found a few funny Jews who mirrored their anxiety. They welcomed and embraced the victimized Jewish sensibility of displacement.”

Robert reads as stubbornly independent, interested only in the judgments of his older brother Charles, God, and his own conscience.

But in Milford, Robert was thirteen, scrawny, with Coke-bottle-thick spectacles and two false front teeth, which were necessary after he tempted fate and took a hunk of cinder block to the mouth back in Oceanside. “In the high school I went to,” he remembered, “there were a lot of farmers and poor kids. They weren’t treated with any respect by the middle class kids at all, just looked upon as dirt, and even if you’re in your teens, if you start reading at all, or if someone turns you on to stuff, it became very clear that there’s something wrong with that. People were looked up to because they had fancy cars, they had fancy clothes, the whole phony charming act they learned to put on. If you’re an outsider and you’re perceptive you can see the picture in a broader perspective.

Also, from the anger and feeling of being an outsider you develop a critical view of things. There’s something wrong with it because it rejects you.” Robert’s sole friend that first year was Mike Britt, a fellow military brat and comics fanatic. Britt’s Milford was “like an episode of Happy Days: ducktails, cars, friends—but [he and Crumb] weren’t in the in-crowd.” The two pals talked comics, collaborated on strips, and skipped catechism classes to go bike riding. Britt was one of the few outsiders who spent time in the Crumb home: “I can remember being at their house and the old man coming into the bedroom and taking the boys’ shoes and polishing them himself. They wouldn’t do it. Eventually he would say, ‘Britt, time to go home.’ Bea was jittery and nervous—she once drove me home on the wrong side of street—but very nice.”

Britt is a constant in Robert’s “School Log,” a handwritten and illustrated diary of each school day of the eighth grade. It is drawn in a style somewhere between Walt Kelly and Carl Barks. His comics are already well composed and paced, and he is his own best character, with Britt making frequent appearances. Robert reads as stubbornly independent, interested only in the judgments of his older brother Charles, God, and his own conscience: he refuses to say the Our Father at school because it’s the Protestant version and decides instead to say it to himself; he is skeptical of a teacher’s lecture on the dangers of horror comic books.

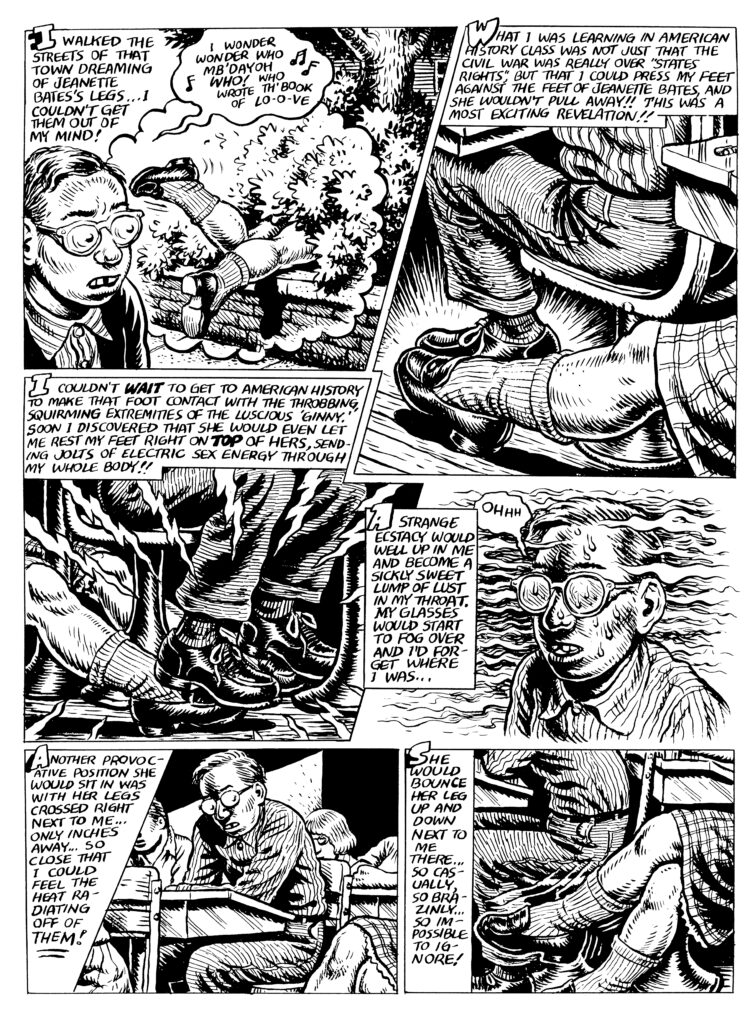

“Footsy,” Weirdo no. 20, 1987.

“Footsy,” Weirdo no. 20, 1987.

He also began experiencing the first surges of puberty. Of prime interest was Sheena, Queen of the Jungle—a dominant female adventurer modeled after Tarzan and played by Irish McCalla in a hokey television show. He would imagine himself on Sheena’s back as she swung on the jungle vines, carried away from his agony. As he fixated on strong women, he focused on the lower body: large buttocks and powerful legs. He had begun staring at women’s legs when he was just four years old, accompanying Bea on downtown shopping trips and, from a child’s point of view, focusing on the forms in his direct sight line: women’s legs in nylons with a seam tracing the curves of the calves.

Every leg, especially in those 1940s high-heeled, round-toed shoes, loudly clacking on the pavement, enthralled him. They became the dominant shapes in his field of vision, shapes he wanted to grasp and explore. His female classmates also tantalized him. And it wasn’t just silent flirtation in the classroom. Robert has always been obsessed with displays of physical strength and flexibility—the ultimate counterpoint to his own sense of himself as a brain in a jar, a male incapable of expressing twentieth-century ideals of masculinity, forever rejected by the girls and women he sought. Jeanette Betts sat behind Robert in his American history class. She would place her leg on his seat and Robert would gently pet it. Dolly Hensley sat to his right and he mingled his foot with hers.

Decades later Robert wrote about the erotic charge of his “leg contact” with one of these girls: “Nancy Knicely sat behind me in Mr. Ely’s English class—sometimes I would stretch back & sit on her knees when she pressed up against the back of my chair. She had long, shapely legs. Once I turned around & looked at her & she said, ‘get off my knees’ in a husky, low voice, meanwhile not moving her legs at all.” Like his teeth-shattering martyrdom in Don’t Tempt Fate, these moments are recounted in his 1988 comic Footsy. Rendered in thick, lush brushstrokes that radiate adolescent sweat, the story details the beginnings of Robert’s long-standing sexual fixations.

Robert has always been obsessed with displays of physical strength and flexibility—the ultimate counterpoint to his own sense of himself as a brain in a jar.

The kids had a game at school—throwing a knife as close to the feet of a classmate as possible. In his diary Robert breathlessly described a May 2, 1957, match he would later replay in Footsy: “Jeannie Betts n’ Nancy Dohring were playin’ split with a knife today at 4th period. An’ they had tight skirts on! Jeannie couldn’t throw th’ knife but Nancy could throw it good. She got Jeannie in a real wide split an’ I thought sure Jeannie’s tight skirt would rip. Just when she was about to give up she threw th’ knife about FIVE feet away from Nancy.”

Footsy climaxes in his encounter with one Sally Burton, who towered over him, and to his delight allowed him to cower at her back: “I went over there and stood against her back as if I was using it for a shelter from the jostling hordes while I fiddled with my books and stuff.” The story closes with the adult Crumb brazenly playing footsy with a coworker in the early 1980s. Robert’s storytelling is both filled with teenage lust and absolutely fixated on accuracy. Milford High is alive in these pages—from furniture to wardrobe to the cadence of students walking the halls. Summoning the origins of his sexual identity demanded Robert maintain an absolute fidelity to place and time.

As much as Robert seemed to accept his geek status, Charles tried to come on like a cosmopolitan big shot from California. He was a handsome kid, hair combed up in a pompadour, thickening body outfitted in spiffy trousers and pressed shirts. His obsession with Treasure Island continued, and his focus on its lead actor Bobby Driscoll now morphed into an erotic fixation. He knew he was gay, had known, he would later write, since he was a little boy. The Disney Driscoll was forever young and bright, an object that would never disappoint.

Charles, somewhere between a dandy and the impish prankster of years past, would break into Shakespeare at any moment. He also, less charmingly, called his classmates hicks, clods, or hillbillies, triggering an immediate pummeling. Without any way to assert himself in the social sphere, and even his own drawing beginning to fade, his confidence quickly began to sag. Carol, well mannered, pretty, and social, however, was popular. She ran for class president (Britt, Robert, and Charles dutifully drew two hundred posters for her) and though she didn’t win, she was well-liked in the community. Maxon, still the get-along younger brother, experienced what was likely his first epileptic seizure in November of 1956, but the young Robert was unaware of any larger implications beyond an overnight stay in the hospital. (Maxon’s condition has remained untreated for his entire life.)

In keeping with their peripatetic past and the constant noise complaints from neighbors, in August 1957, just a year after their arrival, the Crumbs moved from their freshly built home on the south side of Milford to an older house on the north side.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life by Dan Nadel. Copyright © 2025. Available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Dan Nadel

Dan Nadel is a writer and curator. His previous books include, It’s Life as a I See It: Black Cartoonists in Chicago, 1940–1980; Peter Saul: Professional Artist Correspondence, 1945–1976; and Art Out of Time: Unknown Comic Visionaries, 1900–1969. Nadel has curated exhibitions for galleries and museums internationally including the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, the Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, UC Davis, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. He is the founder of PictureBox, a publishing and packaging company that produced over one hundred books, objects, and zines from 2000 to 2014, including the Grammy Award–winning design for Wilco’s 2004 album A Ghost Is Born. Dan is the curator-at-large for the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his family.