How Republicans Weaponized Lies to Incite Their Followers

Robert Draper on What Was Behind the January 6 Insurrection

In March 2020, I attended the sentencing hearing of a fifty‐five‐year‐old Utah resident and health‐insurance salesman named Scott Brian Haven. It was a chilly late‐winter afternoon in Salt Lake City. There were no other reporters or spectators in the federal courtroom, except for a few family members and church friends of the defendant and his wife.

Haven wore a shirt and tie, as well as a hooded black jacket. He was pale and his eyes were puffy. Over and over, he muttered tearfully: “This wasn’t. This wasn’t me. This wasn’t me.”

Haven was a Mormon who served meals to the homeless in downtown Salt Lake. He had also gone through two divorces and was struggling to make ends meet, a precarious financial condition that he blamed on Obama and the Affordable Care Act.

Haven loved President Trump. More than that: as a conservative white male, he identified with Trump’s sense of persecution. The conviction that the left was bent on destroying patriotic Americans such as Trump and himself was amplified on the talk‐radio shows of Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity, both of which Haven listened to religiously. Together these elements brought out in Haven a markedly darker side, one he directed at Democrats, who he saw as the enemy.

From March 2017 until his arrest in June 2019, Haven had placed 3,950 calls to the U.S. Capitol switchboard. All of them were made to House and Senate Democrats. His three principal targets were Senator Dick Durbin, Congresswoman Maxine Waters, and House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerrold Nadler. The three Democrats were not randomly selected by Haven. He focused his attention on them because Limbaugh and Hannity had themselves done so—even going so far as to supply their Washington office numbers while on the air. Haven dutifully jotted them down. Then he began calling, sharing sentiments like the following:

“Tell the son of a bitch we are coming to hang the fucker!”

“I will be the first to blow their fucking heads off—that’s not a threat, that’s a promise.”

“I am going to take up my Second Amendment right, and shoot you liberals in the head, you pussy, fuck you!”

The law‐enforcement community exhibited considerable patience toward Haven. In June 2018, a female Capitol police special agent called Haven to issue a warning. After referring to the federal agent as a “cunt” several times, Haven then yelled, “Come arrest me! I would like to fucking beat the shit out of you just for trying!”

Two months later, it was an FBI special agent who called Haven. What Haven told the agent was something that he had heard repeatedly from Rush Limbaugh and other conservative influencers, such that he could recite it as gospel: “Conservatives don’t commit violent acts against political opponents,” Haven informed the agent. “That type of behavior is conducted by people on the left.”

“We’ve become a party that dabbles—not just dabbles: we traffic in conspiracies. And we traffic in lies.”

He then suggested that the FBI would be better off “investigating groups like Black Lives Matter instead of bothering me,” and hung up.

Finally, in November 2018, a Utah‐based FBI agent paid Haven a visit at home. The insurance salesman was not especially contrite at first. He said that the Democrats were unfair to President Trump, that they were also trying to steal congressional and statewide elections in Georgia and Arizona. Though Haven insisted that his calls were nothing more than “just meaningless threats that were made out of frustration,” he agreed not to make them anymore.

For all of two months, Haven was true to his word. But in 2019, the dam broke. In May, the month before his arrest, Haven placed 850 calls, an average of more than 27 per day. On May 23, he said to a staffer in Jerry Nadler’s office, “I’m at his office. I’m right behind him now. I’m going to shoot him in the head. I’m going to do it now. Are you ready?”

Haven was nonetheless stunned when federal agents arrived at his home on June 3, 2019, and placed him under arrest. He was charged with the federal crime of Interstate Transmissions of Threats to Injure and denied bail. Haven spent the next five months in a federal jail cell, at which point the judge decided that Haven had been brought low by the experience. Haven was granted home detention and forced to wear a GPS monitoring device on his ankle until his trial on March 4, 2020.

When U.S. District Court Judge Clark Waddoups asked the defendant if he wished to say anything before being sentenced, Haven stood and fumbled with a piece of paper. “I realized I made a mistake when I got caught up in hate that got stirred up when I listened to the radio,” Haven said in a trembling voice. It had never occurred to him, he said, that there might be more to Nadler than the rancid image presented by the conservative media. During his time behind bars, Haven had learned that the Democratic congressman was in fact a father and grandfather, just like Haven was.

“There’s so much more to know about people than we hear about in the news,” he marveled, while apologizing to Nadler and his staff.

Though Haven did not in any way disavow his admiration for Trump and his contempt for liberalism and the media, he confessed to Judge Waddoups that such beliefs had become a toxic force in his life. He no longer listened to the news. He had disengaged from politics altogether. “I cannot live a peaceful life when I’m involved,” he admitted.

Judge Waddoups sentenced the defendant to time already served, followed by three years of supervised release.

He also held Haven to a rather unusual condition: he could not listen to talk radio again.

“In your case,” said the judge with careful understatement, “it sets off a level of anger that’s not healthy.”

“This party has lost its damn mind,” Adam Kinzinger had said during the February 3 Republican Conference to judge whether Liz Cheney was fit to be one of their leaders. By that, he meant not only its elected officials but also members of his family.

“Oh my God, what a disappointment you are to us and to God!” several of them jointly wrote to him on January 8, two days after Kinzinger had denounced Trump’s incitement of the insurrection. The letter’s closing sentiment was: “Oh, and by the way, we are calling for your removal from office!” Kinzinger shared the letter with the media and said that his conservative Christian relatives had been “misled.” This spurred them to send a second letter, on January 19, which Kinzinger did not disseminate: “So you are also saying that 75 million people and all but 10 GOP Representatives are ‘being misled’ as well?? Seriously Adam, really! You are the one ‘being misled’ (brainwashed) by the Democrats and the fake news media.”

The two‐page handwritten letter concluded with a reference to Speaker Nancy Pelosi: “Perhaps the witch/devil holding the gavel will invite you to her house for ice cream!”

Kinzinger knew where all this was coming from. As his relatives volunteered in one of the letters, they lived on a steady diet of Fox News, Rush Limbaugh, and First Baptist Dallas evangelical minister Robert Jeffress—the last of whom told his followers that Obama’s policies were “paving the way for the Antichrist” and that Trump was the most pro‐Christianity president in history. There was no point engaging with them, from their parallel universe.

Still, Adam Kinzinger’s estrangement from members of his family was hardly anomalous. Rather, it represented the greater sense of exile he was experiencing. Among the ten Republicans who had voted to impeach Trump, only Liz Cheney was more vilified—though for reasons he could not figure out, Trump was far more bent on destroying Cheney than Kinzinger. Was it because she was a woman? Or was it because Kinzinger had served his country as an air force special operations fighter pilot, the kind of certified patriot that Trump could only pretend to be?

He and Trump used to get along quite well. “Hey, you were great on TV,” the president would invariably tell Kinzinger, who had heard from Trump White House officials that the president had for a time considered nominating him to be secretary of the air force. And though it was evident to Kinzinger—an avowed fiscal conservative and military hawk—that Trump “didn’t have a moral center,” perhaps that could be seen as a good thing. Kinzinger would remember thinking, Maybe he can cut deals. This country needs maybe about four years of just cutting through some bullshit, getting some deals done, like immigration spending, infrastructure, all that.

But by 2020, it had become evident to Kinzinger that Trump lacked not only a moral center but also deal‐cutting expertise. That shortcoming rankled Kinzinger, who had won his seat in 2010 on the Tea Party wave. During the Obama administration, Kinzinger’s Republicans became the Party of No. No to Obamacare. No to deficits. No to raising the debt ceiling. Six years of that, and then the Trump administration and . . . No replacement of Obamacare. No infrastructure package. Only waging culture wars and claiming that the president was a victim of a partisan witch hunt.

“The broader concern,” he would lament, “is that nobody, including myself to be honest, knows any different than just being the opposition to everything. Because since I’ve been in politics, and I’m one of the older guys now, that’s all we’ve done. There’s never been real deal‐cutting.”

But in the wake of the Capitol riot, Kinzinger’s concern about the health of his party extended well beyond its legislative failings. “The biggest danger right now,” he would say in late January 2021, “is that we’ve become a party that dabbles—not just dabbles: we traffic in conspiracies. And we traffic in lies.”

Kinzinger had been among the ten House Republicans to vote to impeach the president—and then, less than a month later, among the eleven in the GOP Conference to vote to strip Marjorie Taylor Greene of her committee assignments. She continued to present a conundrum for him and other Republicans. Do they call out Greene’s lies one by one and risk giving her the attention she craved? Or do they ignore her and run the risk that her lies might become the kudzu that swallows up the party’s soul?

Kinzinger had tried both approaches. Neither seemed entirely effective. The committeeless Georgia freshman lived all day on social media, while Kinzinger had professional responsibilities to attend to.

For placing him and other Republicans in this quandary, Kinzinger blamed Kevin McCarthy. The minority leader had gone silent while Greene and her ilk conflated the insurrection and the summer riots of 2020. Soon, McCarthy, too, would be speaking of the two separate events in the same breath. Kinzinger had publicly condemned the lootings and burnings that accompanied some Black Lives Matter protests that year. Still, he said, “You could have burned down the entire city of Minneapolis and it wouldn’t threaten the very foundations of democracy like this did.”

Meanwhile, Kinzinger couldn’t help but notice that McCarthy had defended Greene’s standing in the February 3, 2021, Republican Conference with greater vigor than he had defended Liz Cheney. Of course, Trump despised Cheney and adored Greene. McCarthy in turn believed Trump’s support was essential to win back the House majority.

But, Kinzinger wondered, what kind of majority would it be, with Greene and her friends in the Freedom Caucus—which Kinzinger derisively referred to as the Freedom Club—commanding all the power? This, he believed, was a problem to address now, while they were in a minority and frankly had nothing else constructive to do. McCarthy should be marginalizing the nuts, not indulging them. There would be no time to do so once the House Republicans became the governing party in January 2023.

Kinzinger knew he lacked any leverage. Many of his like‐minded friends in the Republican Conference—Will Hurd of Texas, Martha Roby of Alabama—had seen this trend coming and headed for the exits. Others, perhaps even the majority in the conference, sympathized with Kinzinger’s viewpoint but did not want to risk losing their jobs by saying so. As for McCarthy, he had left a message for Kinzinger following the minority leader’s appeasement journey to Mar‐a‐Lago in late January.

But Kinzinger had not returned the call. He already knew where the leader stood: beside a former president who continued to say that victory had been stolen from him.

“Enough lies,” Peter Meijer wrote on Twitter in response to a February 9 succession of tweets by Marjorie Taylor Greene suggesting that it was Antifa rather than Trump supporters who attacked the Capitol on January 6. During freshman orientation just after the November 2020 election, the thirty‐two‐year‐old Michigander had recorded an introductory video of himself. In it, Meijer—who had served in Iraq as an army reserve intelligence specialist, and later in Afghanistan as a conflict analyst for a nongovernmental organization—described himself as skilled in putting things back together. He was referring at the time to Washington’s fractious ecosystem.

But now Meijer encountered a brokenness that he was almost certainly incapable of fixing. It was his own party, which continued to embrace Trump and to lie on the ex‐president’s behalf.

“I feel like I’m living in an alternate reality,” Meijer told his colleagues during the February 3 conference to discuss Liz Cheney. He, Cheney, and Kinzinger—the three most vocal Republicans in the House to insist that the party’s future must lead away from Trump, not toward him—were now on a kind of island, subjected to ridicule and even death threats. An anonymous caller had managed to obtain Meijer’s cell phone number. The caller had said to the freshman, “We’re going to have a thousand people at your home this weekend.”

The former conflict analyst kept the man on the phone for twenty minutes, eventually cooling him down. Of course, the ones for Meijer to worry about were the individuals who did not telegraph their intentions.

Meijer had stepped out of the four‐hour Cheney conference on February 3 because he had a Zoom town hall already on the schedule. It was the freshman’s third such encounter with his constituents since being elected, and the first since he had voted to impeach Trump.

“We elected you to be loyal to Donald Trump,” one of his constituents said angrily.

No, Meijer politely but firmly disagreed. He had pledged to uphold conservative values and work within the institution, in the manner of President Gerald Ford, who, before becoming Richard Nixon’s vice president and then succeeding Nixon, had held Meijer’s seat in Michigan’s Fifth Congressional District from 1949 through 1973. Never once had Meijer promised to be Trump’s unflagging ally.

“We need to always remember the two lies that, if they hadn’t been told over and over, we wouldn’t have had the insurrection.”

By the end of the town hall, some of Meijer’s constituents said that although they still disagreed with his decision, they respected his forthrightness. Whether that was enough to ensure that he wouldn’t be killed, Peter Meijer had no idea.

“We need to always remember the two lies that, if they hadn’t been told over and over, we wouldn’t have had the insurrection,” Meijer frequently told his constituents. “Lie One: November 3 was a landslide victory for Donald Trump that was stolen. And Lie Two: if November 3 was the steal, then January 6 would be the day for the steal to be stopped.” He would then proceed to trot out the facts, the logic, the statutes, the Constitution.

But some of them, Meijer could plainly see, were unreachable. They would say, “Yes, but isn’t it curious . . .” Or “Well, there’s just things we don’t know . . .” Or “But I saw on Facebook where . . .” Several of his Michigan constituents had traveled to Washington for the Trump rally on January 6. He didn’t know if any of them had forced their way into the Capitol.

The freshman was more than ready to get past all this. He hadn’t run for office so that he could be spending so much of his time helping fellow Republicans ferret out truth from fantasy. The Meijer family owned more than two hundred grocery stores across the Midwest. Their wealth exceeded $7 billion, according to Forbes. Peter Meijer didn’t need this job, or any other job.

Still, he wanted to influence the national debate, particularly on foreign policy. His experiences in Iraq had caused him to regard that war as a disaster, which put him at odds with Cheney and his new friend Kinzinger, who were both far more inclined to support military action. It was the kind of debate Republicans should be having, instead of fighting over Trump and QAnon. Meijer deeply admired Liz Cheney’s fortitude. The difference between her and McCarthy was, in his view, the difference between true leadership and management. And yet Meijer did not wish to find himself painted into the corner where Cheney and Kinzinger now resided. He did not want to be defined by Trump.

But perhaps it was already too late for Peter Meijer and the other nine impeachers. As he acknowledged to his colleagues during the February 3 conference, “I’m getting raked over the coals. And I probably won’t be back here in two years.”

Two weeks after Meijer uttered those words, Rush Limbaugh died at the age of seventy, after a long battle with cancer.

In the manner of a fallen president, the godfather of conservative radio was ferried from his mansion in Palm Beach to an airstrip where a private plane flew his body to St. Louis, Missouri, Limbaugh’s native state. There, a horse‐drawn carriage conveyed him to the chapel at Bellefontaine Cemetery, to the soundtrack of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” a Limbaugh favorite. Rather unlike the bombastic host who called himself “El Rushbo,” the affair was attended only by family and not disclosed to his admirers until several days after the fact.

News of Limbaugh’s death on February 17 prompted cascades of mournful veneration from his conservative devotees. “Rush Limbaugh was a legend in the conservative movement and an American hero,” Paul Gosar wrote on Twitter that afternoon. The following day, Gosar and forty‐three other House Republicans cosponsored a resolution “commending Rush Limbaugh for inspiring millions of radio listeners and for his devotion to our country.” H. Res. 133 was referred to the House Committee on Oversight and Reform—where, given that the committee was controlled by Democrats, the legislation instantly joined Limbaugh in death.

A week later, on February 25, Ralph Norman of South Carolina requested on the House floor “to allow a 30‐second moment of silence for the passing of Rush Limbaugh, one of the greatest hosts ever.” Norman’s request was denied.

Limbaugh’s fervent conservative admirers were hardly wrong, however. As Peter Meijer knew from interactions with his constituents, as Adam Kinzinger knew from his own family, and as Judge Clark Waddoups had noted in the Utah federal court a year before Limbaugh’s death, the radio host’s influence on the Brian Scott Havens of the world was impossible to overstate.

In his last months, El Rushbo—to whom President Trump had previously awarded the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom—had one final contribution to make to his country. On December 16, 2020, the radio host shared with his 27 million listeners a personal theory about how the upcoming January 6 certification vote could play out. Built on misguided assumptions (such as that both Georgia Senate runoff races would be won by the Republicans) and a dubious interpretation of constitutional law, Limbaugh offered up a complicated scenario in which the Senate and House separately picked a Republican president and vice president.

After that occurred, Limbaugh posited, Speaker Pelosi would object, the office of the presidency would remain vacant past January 20, and ultimately the conservative Supreme Court would rule in Trump’s favor and return him to power. “A long shot,” Limbaugh conceded. Still, he said, it was only fair “to take down Biden,” because Biden had tried to do the same to Trump earlier, via some grand conspiracy in the Obama White House that Limbaugh had hallucinated for the purposes of this discussion.

“The American left is made up of a lot of people that hate this country,” Limbaugh reminded his conservative listeners. “Hate is a very, very destructive frame of mind, it’s a very destructive characteristic, and eventually it results in an implosion. You cannot survive on hatred. You cannot sustain a movement based on it.”

This, he said, was why the “74 million plus and growing” Trump supporters were determined to march on Washington on January 6. “They want to take some kind of action to the left that, ‘We’re not buying this. You didn’t win this thing fair and square. And we are not just going to be docile, like we’ve been in the past, and go away and wait till the next election.’”

As it turned out, Limbaugh was prescient. Hate could not sustain a movement without destructive consequences.

Still, Limbaugh did not quite see that as the lesson to be drawn from January 6. What took place at the Capitol, he told his audience the following afternoon during what would be his final month as a broadcaster, was nothing compared to the damage done to America by Black Lives Matter activists. “Republicans,” he reminded listeners, for perhaps the thousandth and final time of his life, “do not join protest mobs. They do not loot and they don’t riot.” The “tiny minority” that did so at the Capitol, he said, were “undoubtedly including some Antifa Democrat‐sponsored instigators.”

But then, having just finished condemning destructive behavior as the exclusive province of the left, Limbaugh noted that “there’s a lot of people calling for the end of violence. There’s a lot of conservatives, social media, who say that any violence or aggression at all is unacceptable, regardless of the circumstances.” He added, “I’m glad Sam Adams, Thomas Paine—the original Tea Party guys, the men at Lexington and Concord—didn’t feel that way.”

A day after having spoken of the Capitol riot and the American Revolution in the same breath, Rush Limbaugh on January 8 had a new thought about what had occurred two days earlier. “We got set up again,” he declared.

Cryptically, he added, “They knew we were coming. And they had a little surprise plan.”

It was Rush Limbaugh’s final tour de force of zigzagging logic. Time to stop being docile! Only the left believes in violence! Thank God America’s founding patriots believed in violence! The January 6 patriots were set up by the violent left! He had said it all before, and so had Brian Scott Haven, and so would others whose minds had been shaped by Rush Limbaugh’s conspiratorial depiction of America. In this manner, he would live on.

__________________________________

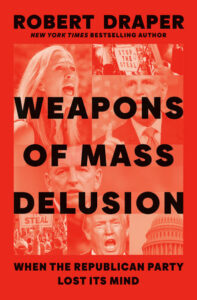

Excerpted from Weapons of Mass Delusion: When the Republican Party Lost Its Mind by Robert Draper, available via Penguin Press.

Robert Draper

Robert Draper is a writer at large for the New York Times Magazine and a contributing writer for National Geographic Magazine. He is the author of several books, including the New York Times bestseller Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush. He lives in Washington D.C. with his wife, Kirsten Powers.