How Prince Helped Me Feel Seen

James Tate Hill on the Multifarious Legacy of the Artist Formerly Known As

A world without Prince was impossible to imagine. By 1993, he had given us “Little Red Corvette” and “1999,” “Raspberry Beret” and “Kiss,” “Batdance” and “Cream” and Purple Rain—the song, the album, and the film. On the 14 studio albums he had released, the producer listed in the credits was always Prince. The songwriter? Prince. Vocals, guitar, keyboards, drums, bass, unless otherwise noted? Prince. “My Name Is Prince,” he sang on the opening track of 1992’s album whose title was only a symbol, but a year later he was telling us Prince no longer existed.

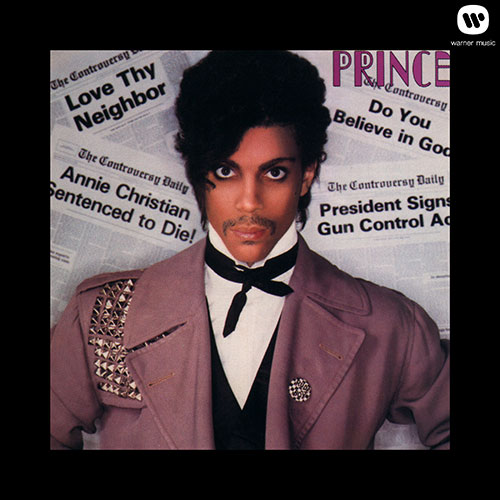

Through a publicist, the artist born Prince Rogers Nelson informed the media that he could now be addressed by that unpronounceable symbol on the cover of his most recent album. Fans were familiar with the glyph, an amalgam of the gender symbols for male and female, which had adorned his guitars, liner notes, and concert decorations for years. The line between masculine and feminine was one of the many binaries Prince had blurred his entire career. “Am I black or white / Am I straight or gay?” he sings on the title track of 1981’s Controversy, an album whose cover finds Prince wearing eyeliner, rouge, and a suit with a skinny tie.

If the explanation for Prince’s chosen symbol made perfect sense, the logistics of how one might address someone without a name were less clear.

“What are we supposed to call you?” Asked nearly everyone who interviewed him in the coming years.

The Artist Formerly Known as Prince would flash a sly smile that seemed to say, Why do you need to call me anything?

![]()

My senior year of high school I changed my own name, if only on paper. After losing much of my eyesight the previous year to a rare genetic condition, I adjusted my career goal of doctor to physical therapy. I moved from the driver’s seat of my preowned Mustang to the passenger side of my parents’ Civic. I began reading with my ears instead of my eyes and, unable to play my video games, this became my primary pastime. Eventually, equipped with a microcassette recorder and a mom willing to type what I dictated, I started writing my own stories.

“If I gave you something I wrote,” I said, standing nervously in the cubicle of my English teacher, “would you, like, read it and tell me what you thought?”

“Is that it there?” Mrs. Jones, who had the warm and easy smile of moms in old sitcoms, pointed to the six double-spaced pages in my hand. She also had, in the year I was adapting to vision loss, a way of knowing when I was asking for more than her time.

In the story I gave her, an everyman has to answer a riddle posed by an ethereal gatekeeper. The assassination of John F. Kennedy was somehow involved. It was pretty deep, much more philosophical than the pedestrian classics we had been reading in class.

“I don’t think I get it,” Mrs. Jones told me a week later.

“Which part?”

My teacher turned pages until she came to the end. “All of it, really.”

I should have been discouraged. Instead, I went to work on another story, and another one after that. Mom typed them up and I delivered each one to Mrs. Jones’s cubicle before first period. After her response to my first story, I didn’t ask for feedback. I was surprised, therefore, when she told me after class how much she loved my latest effort.

The new story involved a small-town widow wrongly suspected of killing his wife in a fire. She thought it was very moving, she said, and I could hear the smile around her words. The scene in the post office where everyone is staring at him was so vivid, she said. She wanted to teach it, she said.

“Do what?” I said.

“Can I? We’ll use a pen name, of course.”

So I became J. Griffith Chaney, the birth name of Jack London, listening anxiously while my classmates discussed what I hoped they thought was the literary product of a long-dead master. I had worried the Xeroxed, double-spaced pages would betray our ruse, but people seemed to think Mrs. Jones loved this obscure story so much she had typed it up herself. No one had much to say about the eight pages I titled “Bane,” but with graduation two weeks away no one had much to say about “A Rose for Emily” either. My classmates, from whom I had tried so diligently to keep my new limitations a secret, did seem impressed when they learned I was J. Griffith Chaney. Mrs. Jones revealed my identity on the last day of class, not telling me she was going to, and I wished she had maintained my anonymity. The best part about people reading something I had written was none of them knowing it was me.

![]()

I was seven years old when Purple Rain hit theaters, and Prince was as confusing to me as an evening soap or a library book without pictures. Even as a teen, I couldn’t quite wrap my head around this strange man or his music. After graduating from college, living in a tiny apartment converted from an old hospital, rejected by the creative writing programs to which I applied, sometimes going days without saying a word to another human being, the music of Prince finally spoke to me.

“If I listened closely, subliminal wisdom about love and faith and identity seemed to arrive in a single guitar note.”

I had begun college as a psychology major because listening to other people’s problems seemed like a job someone with low vision could do. Upon learning you could take creative writing classes, major in it even, I shivered with thoughts of pursuing something I actually enjoyed. One snowy afternoon sophomore year I asked my friend Danny, the most talented poet in our class, if he’d read my novel in progress and tell me what he thought. Danny’s poems were eight-page homages to “The Waste Land” about the death of his girlfriend the year before. All my poems were parodies of other poems in our textbook.

I opened the file containing the 35 pages I had written after teaching myself to type last summer. I performed the keyboard shortcut for reducing the font to 12 points from my default setting of 240. This was the first time I had let someone other than my parents see my unadjusted font. Danny sat in my desk chair and began to read. The novel’s main character was a writer sitting in the corner booth of a diner who, after 30 pages, had not moved from his booth or been joined in the narrative by other characters.

“Well?” I said when Danny got up from my desk.

He mentioned a couple of lines he had liked.

“It’s still really rough,” I said.

“Don’t take this the wrong way,” he said, “but I like your poetry better than your fiction.”

My writing did improve, or so I thought. One of my professors, the poet laureate of the state, thought I should apply to graduate programs in creative writing. By March, only one school, the famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop, had not yet made its decision. When the thin envelope arrived, I ducked into the men’s room across from the campus post office. The letter-by-letter pace of reading with my 22X magnifier let my mind jump to a dozen conclusions before the end of a given sentence. “This year we received eight hundred seventy-two applicants in fiction for only twenty slots. Unfortunately . . . ” continued the letter that completed my set of rejections. Two weeks earlier, Danny had gotten into the only MFA program to which he applied. If only I had a girlfriend who had died, some authentic pain I might transform into art.

Prince said he learned from Miles Davis that silence is a sound. This was a sound I perfected in the two years after college. Instead of short stories, I steeped myself in all things Prince, working on a paper about the identity politics of his name change. The 12 pages contained more song lyrics than quotations from the identity politicians I studied in the graduate literature program I was attending.

“Sounds promising,” said my African American Narratives professor, a thirty-something Caucasian woman, and I had never heard anyone lie less convincingly.

A state agency that assists people with disabilities paid for any school-related readers I might need, ostensibly for handouts and books not available on cassette. The student assistant who met me in the library seemed amused when we only ever searched the internet for Prince interviews, reviews of his albums, and any criticism about the film Purple Rain, which might or might not have been for a presentation in a course called Autobiography and Biography. My primary research was the infinite hours listening to Prince’s music, analyzing the lyrics and soundscapes the way others meditate or commune with nature. If I listened closely, subliminal wisdom about love and faith and identity seemed to arrive in a single guitar note. I had no formal education in music, but maybe it was true the blind can hear things normal people can’t. I didn’t know if the truths in “Lady Cab Driver” and “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker” stayed with me when the song ended, but the closer I listened the less I could hear my own silence.

*

In 1982, opening for the Rolling Stones in the biggest break in his career to date, Prince was booed off the stage by audiences largely unfamiliar with his music. Around this time, it should be noted, he sometimes performed in a trench coat and G-string, his stage choreography as sexual as lyrics like “I’ll jack you off” and “incest is everything it’s said to be.” Prince had already flown home to Minnesota when Mick Jagger convinced him to return to the tour. Two years later, many of the same fans from that tour would make Purple Rain one of the bestselling albums of all time and one of the top films of 1984. In one of the movie’s more memorable scenes, Prince writhes onstage, wailing about a sex fiend named Nikki whom he encounters in a hotel lobby, masturbating with a magazine. In her review for The New Yorker, Pauline Kael draws attention to Prince’s delicious update to Jimi Hendrix setting his guitar on fire: Prince’s guitar seems to ejaculate.

The masturbation in “Darling Nikki” famously inspired Tipper Gore’s crusade for parental advisory labels on music with mature content, a label which, ironically, wouldn’t adorn any of Prince’s albums until 1992. Prince’s frank sexuality would always be a trademark of his music and persona, but the carnal glint in his eye coexisted peacefully with a strong belief in Christianity. According to one of his band members, sex to Prince was religion, desire and faith residing in the same part of his soul. On Sign O the Times, only a few tracks after Prince croons “let’s get to slammin’” and “let me kiss you down there, you know, down there where it counts,” another song warns not to die “without knowing the cross.”

If Prince’s lyrics straddled the incongruous line between Christianity and pornography, they were only one of the ways he resisted definition. His music blended elements of rock, rhythm and blues, jazz, funk, and new wave to create his trademark Minneapolis sound. The music industry insists on labels, though, and they relegated him to R&B radio until his fifth album, 1999, crossed over to the mainstream. From then on, his audience, like all his backing bands, were a melting pot of diversity, racial as well as gender.

“To listen to Prince was to hear possibility, to believe in a world beyond definitions, beyond measurables and absolutes.”

Prince even looked like the offspring of mixed race parents. He could be coy about his racial identity, and the myth that he was biracial gained purchase when European actress Olga Karlatos played his mother in Purple Rain. In interviews early in his career, Prince himself intimated he was part Italian, but both his parents and all his grandparents were African American.

I didn’t see Purple Rain until my early twenties, but I had watched Prince’s music videos countless times before losing my sight. My optic nerves, in other words, can’t be blamed for my erroneous belief that Prince was 6’4” in height. A friend in college told me as I was getting into Prince that he was—apparently quite famously—barely 5’2”. Had I not noticed the high heels? Was he filmed, like diminutive movie stars, from favorable angles? It’s possible I simply hadn’t paid any attention, but what I think I saw was an enormity my mind couldn’t equate with such a small body. Watching Purple Rain for the first time, my face inches from the TV, Prince still seemed tall in ways that had nothing to do with the tricks my eyes now played on me. To listen to Prince was to hear possibility, to believe in a world beyond definitions, beyond measurables and absolutes.

*

Midway into the graduate literature program, I dug my microcassette recorder out of the closet. My three-disc changer loaded with Prince, I began crafting a narrative about a journalist interviewing a mysterious rock star who went by a single name. Other stories followed, most of them set in the world of professional wrestling, my other obsession at the time. I didn’t know if they were any good, but I kept writing because it felt better than not writing.

“It’s amiable,” said an award-winning author about my first short story as a graduate student of creative writing. “I’d borrow tools from it, but I wouldn’t buy it a beer.”

I felt lucky, after two years studying critical theory, to have gotten into a respected writing program in Virginia. At the same time, I saw myself as one of the weaker writers. A classmate had already published a short story collection with a major New York press. When the second story I turned in didn’t go over as well as the first, I grew nostalgic for the faint praise of amiability. The novel I was working on wasn’t going any better. In it, a generic man with amnesia is taken in by a generic woman, and together they spend a lot of time not knowing how to fill the pages of a novel.

“Why don’t you write about losing your eyesight,” a classmate asked me at the bar after our evening workshop.

I might have winced at her suggestion.

“You don’t think it’s interesting?”

I shook my head. A burnout of my optic nerves and its effect on my modest dreams was a worse plot than my aimless novel. More than this, the thought of readers, total strangers, knowing I was blind, disabled, felt like the opposite of why I wanted to be a writer.

Most evenings my classmates got together to hang out, but none of them was particularly into Prince. Even the fiction writer from Minnesota was only a casual fan, which seemed like someone from Vermont thinking maple syrup was an adequate topping for pancakes. When Prince announced a series of pop-up concerts, I was elated that two poets were up for the three-hour pilgrimage to DC.

Months earlier, quietly and with little fanfare, Prince had become Prince again. His original contracts with Warner Bros. had expired, and he felt free to reclaim his birth name. Before becoming the symbol, Prince began showing up at meetings with the word slave painted on his face. He had become fed up with the control Warner Bros. exerted over his music, including the label’s ownership of all his most famous works. If he couldn’t free himself from his contracts, he would free himself from the person who had signed them. Because I had explained and defended the name change so many times, I had mixed feelings about the announcement.

Who was the Prince we were driving to see? Screen-reading software finally allowed me to surf the Internet, and I devoted several hours a week perusing entertainment news and Prince-related message boards. Fans posted set lists of recent shows, complaining that he was changing lyrics from some of his bawdier songs. In “Get Off,” for example, “23 positions in a one-night stand” had been revised to “23 inscriptions in a one-night stand.” The role of religion in Prince’s life, always present, had grown exponentially in the last few years. The fervor with which he mentioned Jehovah in interviews didn’t feel right. He was supposed to be everything, not one thing.

Secretive as Prince was about his personal life, the reasons for his becoming a Jehovah’s Witness weren’t clear. I hadn’t read much about the death of his newborn son, which he had continued to deny for weeks after it happened. I hadn’t known that his marriage was ending. No one knew the boy’s name, wrongly attributed for years as Gregory, was actually Amiir. And for two hours in Fairfax, Virginia, to my trammeled eyes, the perambulating blur onstage was the Prince I had always known, the Prince he wanted us to see, a total enigma.

*

The second time I saw Prince was in Raleigh on 2004’s Musicology tour, with the girl I would marry two years later. After dozens upon dozens of rejections, a small literary journal in Texas had just published my first short story. I recently finished a rewrite of a novel a writer I looked up to said had commercial appeal. Soon a literary agent whose clients I had studied as an English major would offer me representation. I could feel myself becoming who I had always wanted to become.

Musicology was hailed by some as a comeback, a return to form. More than the new songs, fans came to see Prince, and after an inscrutable foray into religious allegory with 2001’s The Rainbow Children, Prince seemed his vintage, playful self. The year marked the 20th anniversary of Purple Rain, and his live shows contained so many hits he had to squeeze them into hit medleys. MTV, who hadn’t played Prince’s music in over a decade, honored him with a primetime special. Entering his late forties, about to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility, Prince seemed not at all surprised and a little amused by the renewed attention.

“To most, he had never stopped being Prince, and maybe nothing ever changed except the words people used to refer to him, but I admired his attempt to escape a label, even one as inexorable as a name.”

My poet girlfriend and I had nearly broken up the previous year. An initially misdiagnosed autoimmune disorder made for a household with two disabilities, and couples counseling didn’t answer the question of whether or not we should—or could—stay together. Following a proper diagnosis and effective treatment, she seemed like herself again. We seemed like us again. It was impossible to believe, bathed in the purple light of Prince’s second encore, that our marriage would last a single year. It was impossible to believe my agent would one day call with the news that the last publisher to whom we had sent my novel would not be purchasing it. It was impossible to believe, hearing the ageless voice of Prince singing he only wanted to be some kind of friend, that he would be dead at age 57.

Reviews of the Musicology tour noted how youthful Prince looked. Articles said the same in the months leading up to his death. My eyes were in no position to disagree, in either year. In my mind’s eye, Prince was 6’4” and eternally 25. I couldn’t picture the man taking so much pain medication that his plane made an emergency landing so doctors could revive him. Another overdose a week later would take his life, but a day after the plane overdose Prince led an all-night dance party, brushing aside reports of his poor health.

In the wake of his death, many close to Prince would characterize him as healthy, energetic. Some of these descriptions must have come from the same friends who kept his painkiller addiction so well hidden. His chronic pain must have at least predated his double hip replacement surgery in 2010, necessary from decades of dancing on those high heels. In her memoir, Prince’s first wife recalls an unexplained incident in which he asked her to retrieve a bottle of pills from their hotel room which he didn’t want anyone to find, a story she kept to herself until the book’s publication after his death. Days before he was found unresponsive in the elevator of his home, Prince had been seen riding his bicycle around the parking lot of a strip mall. A teenage girl saw him resting on the sidewalk and took out her phone to snap his picture. Prince asked her please not to photograph him. She put away her phone, honoring his request.

*

“I won’t be complicit in your lie,” my wife wrote in an email two months into our marriage.

I wasn’t sure which word hurt more, lie or the B word embedded so thornily in the next line. Blindness. Your blindness. Hiding your blindness. If she knew how deeply that word wounded me, would she have refrained from using it or moved it from quiver to bow years ago?

I had not hidden my disability from her when we met, but my efforts to downplay it while we were falling in love probably convinced her I was someone different from who I was. Perhaps I had convinced myself. Whatever the case, her impatience with everything I couldn’t do never made my charade feel like a bad idea.

The failure of my novel was no easier to process. The book’s plot centered on an accidental friendship between a professional wrestler and a small-town copy editor, who joins the wrestling promotion as a referee to the horror of his fiancée. Rejections from publishers cited marketing concerns. A story set in the world of professional wrestling wouldn’t appeal to women, and men, they said, don’t really read. One editor found the wrestler character far more interesting than the narrator, and I didn’t disagree. After all, in the original short story from which the novel grew, the wrestler had been a mysterious musician based shamelessly on Prince.

Not surprisingly, neither divorce nor a failed novel made for a golden age of creativity. Feedback from friends on another novel I recently completed was mixed. All my ideas for revising it required more mental energy than I could summon when I opened the file. I worked on a few short stories but never managed more than a few paragraphs. A quotation from F. Scott Fitzgerald I used to include on my composition syllabus kept flashing in my head: “You don’t write because you want to say something, you write because you have something to say.”

That fall a friend talked me into attending a poetry reading by a fellow alum of our writing program. The poet was a friend of my friend, but I hadn’t known her well. Nor did I get excited about poetry readings, despite—or maybe a result of—having been married to a poet. Nevertheless, I listened in awe as our former classmate read poem after poem about her disability. Her physical difference would be obvious to someone with better eyesight, but to me she was only the lines of her poems, each stanza a flag planted in the center of her life: This is me, and this is me, and this and this and this.

The next day I scanned the pages of her poetry collection into my computer, translating the text to digital speech. I read it in a sitting. I reread it later in the week, envious of how starkly each poem announced who she was. That her disability was apparent to people she met was nothing to envy, but my ability to pass for sighted had begun to feel like the problem rather than the solution.

*

Two chapters into my next novel, I already realized what was missing, why the story I was telling didn’t sound true. I started over, trading my nondescript narrator for a blind protagonist. A decade and a half before that novel became my first book, two decades before completing a memoir about a life spent trying to hide who I was, I unwrapped the latest album by an artist who seemed to change his identity whenever he wished. If Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic didn’t ascend to the stratosphere of Prince’s own best work, it was a more commercial effort than other recent albums, featuring guest stars like Sheryl Crow and Gwen Stefani. After listening to it a few times, I held my 22X magnifier against the liner notes. As usual, the text was barely large enough to read, but deductive reasoning helped me piece together most of the credits. My mind took longer than my eyes to make sense of what I was seeing. Where for years there had been only the unpronounceable symbol, the production, songwriting, vocals, and instruments not credited to guest artists were attributed to Prince.

Rave’s liner notes foreshadowed the announcement in six months, after the expiration of the Warner Bros. contracts, that the Artist was going to be Prince once more. To most, he had never stopped being Prince, and maybe nothing ever changed except the words people used to refer to him, but I admired his attempt to escape a label, even one as inexorable as a name. Who we are, he told us, can’t be contained in a single word. Maybe, he was saying, it doesn’t have to be.

To promote the new album, Prince appeared on Larry King in one of the only live television interviews of his career. He took questions from callers, correcting King’s use of the word fan. “Fan is short for fanatic,” he said in the soft, reserved voice that belied his wilder stage persona. “I call them friends.” Most friends addressed him by his still-preferred moniker of The Artist, but he didn’t seem to mind when someone referred to him as Prince.

“It’s so good to see you on TV,” said one caller.

Prince smiled. “It’s good to be seen.”

James Tate Hill

James Tate Hill is the author of a memoir, Blind Man’s Bluff (W. W. Norton, 2021). His fiction debut, Academy Gothic, won the Nilsen Literary Prize for a First Novel. He serves as fiction editor for Monkeybicycle and a contributing editor for Lit Hub, where he writes a monthly audiobooks column.