Between the Cane Rows: Principles of Making in the Cycles of Power

Patrick Rosal on Family History, Language Ecosystems, and Life in the Cane Fields

It is a human love, I live inside.

Article continues after advertisement–Amiri Baraka, “An Agony. As Now.”

*

There’s a video of the late great Cuban percussionist, Tata Güines, giving a demonstration of Afro-Cuban music—and the role of the drums popularly called congas—to students in Bordeaux, France, 1991. The drums have many names, depending on their size and function inside an ensemble. In Cuba, they are often generally referred to as tumbadoras. On stage with Tata Güines is a Spanish-speaking companion (and another man off screen translating the two men’s presentation into French). Tata Güines’s compañero urgently but respectfully interrupts the percussion maestro to clarify for their audience the terminology and naming of the drums. The man speaks deliberately and emphatically:

[La palabra tumbadora] tiene su antecedente fonético en el grupo lingüístico Bantú en África. Viene un término: mmm-bah. De mmm-bah viene tummm-bah [tumba]. Y de tummm-bah viene tummm–mmm-bah–doh–rah y es así que queda el orígen fonético africano en el medio de la palabra castellana—casi imperceptible.

*

My grandfather was a laborer in the sugar cane fields on the windward side of the Big Island, Hawai’i, during the late 1920s and early 30s. Apolonio Gelacio was a sakada, a manong. He cut sugar cane for a pittance. He was referred to by a number—a bango, as it was known, #936—a referent for the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association to keep very specific track of his production, his wages, his expenses and arrears.

In America, those sugar fields are often called canebrake, which ostensibly refers to the breaking and processing of cane so it’s suitable for consumption, but I imagine it was also a place to break the wills of laborers.

My grandfather, like other sakadas, would buy many of his supplies, medicine, and whatever else he needed at the end of the week from the plantation store. And these Filipino workers were often charged the balance of their weekly wages, on top of which a poll tax was exacted, which left them with very little in terms of actual earnings; often, it left them in debt. My uncle tells me that the sakadas spent grueling hours planting and harvesting, swinging a machete at the stalk’s root—hundreds and hundreds over the course of a day—and bearing the heavy bundles back and forth for transport. The crops were a visible measure of their productivity for which they were pitifully remunerated and frankly treated like shit.

So, what my grandfather and the other manongs did was plant their own micro crops in between the rows of cane. I could imagine long beans doing well in those fields, maybe even okra or squash, maybe sweet potato too, not just for the tubers, but for the leaves and hearty stems. And maybe the men fed each other from those illicit gardens, then gathered in a bunkhouse in Pahoa to barter their greens for rum or cigarettes or a good knife. And I’m sure, there, in between the rows, beyond the direct gaze of the bosses, they didn’t just plant seeds and reap their fruit, they also gossiped and cursed. They dreamt. They danced. I’m sure they sang. My uncle told me that my grandfather became a great practitioner of the Philippine stick fighting art, arnis—known as kimat in Ilokano, which means lightning. There, in between the thick grasses whose fibers would be processed to become the innocuous sweetness of tables across the continent of America, my grandfather and his comrades would literally learn to fight for their lives—casi imperceptible.

*

Here’s what I have come to learn: a system will construct a language or a field. And inside that strategically fixed construction, its subjects are expected to abide by the order of the given system.

And I’m sure, there, they didn’t just plant seeds and reap their fruit, they also gossiped and cursed. They dreamt. They danced. I’m sure they sang.But those very subjects will learn to do whatever they can in order to eat and fight and laugh and mourn and survive. And so, though largely illegible to those who are invested in the integrity and perpetuity of that same system—right smack in the middle of the emblems of its power—a recurring form emerges: the cultivation of the shapeshifting, elusive, lethal, polyglottal, elaborate, sometimes gorgeous improvisations of material-at-hand. And such improvisations require a plethora of qualities and skills—observation, curiosity, gathering, experimentation, collaboration, concealment, nerve, deception, discretion, wit, among others. We make a living out of the things a system prohibits, refuses, denigrates, and throws away. We study everything.

*

As a boy I felt the pressure of language, which is the pressure and illusion of containment, not just the pressure of proper pronunciation and usage, but the pressure to conform to a language’s portrayals of my world, of me. Over time, I believed that one of two things would happen: the pressure (of a name, a word, a category) would either break me or I would have to find the fracture in the container and bust the fuck out. I chose—naively, romantically—the latter. Little did I know, the box remakes itself. The box is regenerative… But so, too, are its fissures. And one way to begin to break any box open from the inside is to bang on the walls and listen to its faults. Even if I couldn’t crack the box, the banging made a music that couldn’t be contained.

And one might go as far to theorize that the sounds I have made change the space that encloses me. Some might say that space is America. That theory might or might not prove to be true. The manongs’ exuberantly secret disobedience between the cane rows did not grind the sugar industry to a halt. Nor did our linguistic creolizations in the Americas and Africa and the Pacific extract or eradicate the Iberian idiom from our governance or names or song. Not in any clear or absolute way, anyway.

Sure, it could be that the history of making, its infinitely complex processes, and all its imperfect objects have instigated some change in the world. Personally, I can’t say for sure. The only change I can attest to is my own imagination. There’s nothing special about this change—nothing politically radical, but actually something quite natural.

The poetic principle that says a field of industrial crops can be turned into a dance floor and that a Spanish word for drum can be turned into an invocation to ancestors is also a principle that suggests, a sinner is not simply a sinner because a society and its systems need a sinner, nor is a king simply a king, nor is a thief just a thief. And none remains any one thing forever. For example, tomorrow they could all be a river.

*

Ritual, the encoding of memory into the body by sound and movement, communication with the dead and the yet-to-be-born, “performances” in which everyone present is invited to participate, call and response, the appropriation and reinvention/recontextualization of a widely disseminated or familiar artifact, the fragment as compositional element, the fundamental practice of observing and getting to know the land and material that are right in front of you, feeling as a route to and from the imagination, feeling in collaboration with reason, keening, the juxtaposition of unlikely elements or objects, a spirit of play, the revelation of the expressive potential of something commonplace, the fluid boundary between storytelling and song—these are not innovative artistic practices, let alone entrepreneurial opportunities; these modes are so old. These modes of study were preserved and reinvented by many who came before me. And my job as an artist—as I see it—is to preserve and reinvent the soul of those modes and practices to the best of my attention and skill and love.

I like to believe if I listen close enough, I might hear what we all used to be; I like to believe we might briefly grasp what we might become. A practice of justice must contain within it a sense of the certainty that things and people can and will change, and a sense of justice must also contain the uncertainty of who, what, where, how, and why…

I suppose I keep writing and making music and art because somewhere in our attention to this uncertainty we ourselves are changed. And just as important, we might catch a glimpse of a genesis, which is both heartbreaking and hilarious.

And that might be the first and last thing that ever really matters.

__________________________________

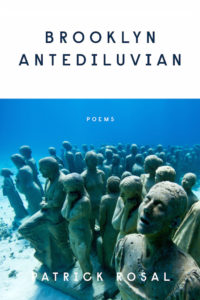

Brooklyn Antediluvian: Poems by Patrick Rosal is available now via Persea Books.