How Paris is Burning Left an Indelible Mark on Pop Culture

Ricky Tucker on the Magic of Queer Blackness

I was of a very impressionable age—around twenty-two—when I first watched the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning. Many circumstances conspired, I believe, to bring Jennie Livingston’s breakthrough film into my line of vision: Leaving the South for Boston and meeting my first boyfriend, who was also my first art school boyfriend. A liberal exploration of drugs that unlatched years of internal homophobia followed. And then there was the opening of Video Underground in 2004, a Jamaica Plain safe haven for progressive ideas cinematically captured for critical consumption.

It’s an understatement to say that Paris Is Burning was everything to me. Seeing it finally put a name on what I had somehow known existed perhaps through family conversations, run-ins in the city, and pop cultural dots connected over a couple decades of life—BALLROOM. I was finally able to say, “There it is!”

My takeaways from that cult classic are numerous: The dulcet tones of Pepper LaBeija, draped in silk in a lamplit corner, chain-smoking and unravelling the yarn of how she became the next mother of the very first house in Ballroom, the House of LaBeija. The soft-faced, sharp-tongued Venus Xtravaganza, laying out the fine details of how to read someone to filth. Though seemingly made of porcelain, she was actually Teflon, only underscoring the tragedy of her later being found strangled under a bed at the Duchess Hotel in New York City on Christmas Day, 1988. The thrill of learning the categories walked. What it must have been like to have been in those rooms then.

For me, the greatest takeaway came from just being able to listen to Dorian Corey lay out the history of ball culture in such a profoundly elegant way. She was a beauty, an enigma, a force, a historian, a grand dame, and a poet. Hearing her say things like, “You don’t have to bend the world. I think it’s better just to enjoy it. Pay your dues and enjoy it. If you shoot an arrow and it goes real high, hooray for you,” told me that contrasts like order and chaos and failure and success aren’t paradoxical or conflicting; they’re one and the same and all around us.

And of course, finding out that the entire time they were filming Paris Is Burning there was a vinyl-wrapped, mummified body hidden in Dorian’s closet was simply revelatory. Evidently, an intruder, perhaps a former lover, broke into Dorian’s home and became violent with her, causing her in turn to shoot him and stuff him into a chest in her closet, adding another captivating level to her narrative. The consequences of homicide for a trans woman would have been, and still are, dire. But also, like a symbol for all of us on the margins of society, what it must have been like to live with that weight. Every. Day. And to still get up and wade through daily routines and major performances, all while looking fabulous? Like I said, she was an enigma, if not a genius at life.

*

She wears a lot of faces: many of them Black, sometimes Kabuki or Latinx, but rarely her own. For better or worse, her singles are at the very least derivatives of authentic Black music, which nowadays, is deemed good enough to download.

Queer Blackness, when fully unleashed, is some kind of mystical, magical commodity sparked from having to constantly laugh in the face of death in the name of life.

I remember when “Vogue” first came out. I was eight years old, and my mother was in the wood-paneled bathroom of my great-grandmother’s North Carolina home, getting ready to go out with her best friend, Reggie, a gay man. They both had roots in New York and in the South, and were known for being way too fabulous for their immediate podunk surroundings.

We were listening to 102 JAMZ, the Piedmont Triad’s local “urban” radio station, when Shep Pettibone’s irresistible synths and snaps began to slowly trickle in across the airwaves. Madonna comes in, robotically demanding that we strike poses, followed by that whispered, goosebump-inducing word, “vogue.” Mommy and Reggie, at first staring into the brightly lit mirror above the sink, respectively teasing and scrutinizing themselves, turned at once to face each other—now struck with incredulity. They listened intently as I watched on blankly.

“Can you believe this, Trix?” Reg asked. He always called her Trixie. “Do you see what this woman is doing?!” My mom didn’t miss a beat. “Yes, honey,” she said. “I guess she thinks she’s one of the children now.”

I tried to remain small, sitting on the corner of the tub as they went on clutching their pearls about how that leech Madonna went and lifted brown gay life right out of the club and plopped it onto the pop charts. I got the feeling from their conversation that maybe most of America didn’t exactly deserve or couldn’t even comprehend such a gift.

Ultimately, I gleaned the fact that secret, precious events go down in the club during those times when I was at home asleep, never able to see the payoff for Mommy and Reggie’s pregame show. As an adult, I later learned that clubs and balls were just as viable a way to come to Jesus as church was. I also figured out that queer Blackness, when fully unleashed, is some kind of mystical, magical commodity sparked from having to constantly laugh in the face of death in the name of life, a rebirth that can never actually be impersonated, like a pigeon that paints itself red and throws on a sandwich board reading “I’m a phoenix. You must believe me.” Girl, sit down.

Two decades later, in New York City, with Paris Is Burning on my mind and in my heart, I registered for the part dance instruction, part theory-focused course “Vogue’ology”—a cerebral and aerobic space that would change my life. There, I was introduced to co-instructors Robert Sember (artist, public health advocate, and cofounder of the Vogue’ology collective), Michael Roberson (theologist, then father of the House of Garçon, and current father of the House of Margiela), the choreographer the legendary Pony Zion (lead member of Vogue Evolution), and vogue instructor Derrick Xtravaganza.

In the course, we learned both vogue technique and ball history, but most importantly, we became a family, something like our own house. We were welcomed into the Ballroom community as allies, joining the fold with a critical/theoretical perspective and an understanding that we should proceed with respect and appreciation for the community—not a desire for appropriation. Trust and mindfulness were front of mind that term, and as Robert Sember once told me in regard to gaining the trust of the Ballroom community: “You have to keep showing up.” So, that’s exactly what I did.

In that first week, we were required only to absorb a lot of information. Source texts, like Marlon Bailey’s rare and stand-alone cultural analysis of Detroit’s Ballroom culture, Butch Queen Up in Pumps, and the late and powerful José Munoz’s breakthrough insight into gender identity and disruption, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, stripped away for us any false curtains of gender and class normativity, exposing our cohort to a spectrum of queer experiences. Documentaries like Paris Is Burning, The Queen (1968), and other footage from Ballroom performances magnified for us the value of Ballroom and the subsequent marginalization and commodification of its population—including Madonna’s live performance of “Vogue,” during the 1990 MTV Video Music Awards.

Madonna mines and plucks from Black culture, commodifying gospel music, pimp paraphernalia, cornrows.

We watched that performance with both rapture and horror as she took the slave/madam of the manor metaphor from the music video and amplified it into a full-on Marie Antoinette scenario, ripe with misdirected class and race cultural codes. It was both aesthetically gorgeous and conceptually horrible. A common prop at balls is folding fans, used to either stoke or keep asunder the flames of fierceness, and Madonna and her two longest-running backup singers, Donna De Lory and Niki Harris (also figures in the music video) use them—and human beings—as props too.

The dancer José Xtravaganza is again a focus. He bends down trying to tend to “Madame X” as she lifts her hoop skirt sensually, only to kick his head away. The opulence is stunning, but just like the crass disparities we live with every day, the highs of the rich and privileged only further accentuate the lows of the marginalized majority. Madonna begins the performance by pointing her fan at each of her dancers while demandingly saying “Vogue,” again tapping them out of a frozen state into campy, couture animation—as if she is the arbiter of dance.

This pivotal moment in her career wouldn’t be the first or the last time Madonna shook one hand with Black culture only to pickpocket it with the other. In videos like “Secret,” “Like a Prayer,” “Music,” and “Human Nature,” she mines and plucks from Black culture, commodifying gospel music, pimp paraphernalia, cornrows (and to this day, grills she never seems to put away)—all tropes and symbols meant to couch her in the cutting-edge credibility of Blackness.

That day in class, in the fall of 2011, after watching this performance, Robert and Michael asked us, “What did you see and what did you hear?” We now saw and heard so much: pomp and circumstance, posturing, beauty, commodification, social hierarchy, ambition, an illusion.

The contradictions went on and on. That friction continues to burn, and it becomes more and more clear that there is a false narrative of ownership created around ball culture.

__________________________________

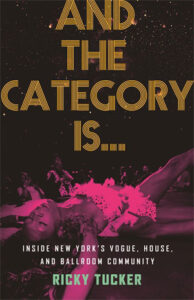

Excerpted from And the Category Is…: Inside New York’s Vogue, House, and Ballroom Community by Ricky Tucker (Beacon Press, 2021). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Ricky Tucker

Ricky Tucker is a North Carolina native, a storyteller, an educator, a lead creative, and an art critic. His work explores the imprints of art and memory on narrative, and the absurdity of most fleeting moments. He has written for the Paris Review, the Tenth Magazine, and Public Seminar, among others, and has performed for reading series including the Moth Grand SLAM, Sister Spit, Born: Free, and Spark London. In 2017, he was chosen as a Lambda Literary Emerging Writer Fellow for creative nonfiction. Connect with him at thewriterrickytucker.com.