How Oscar Wilde Created a Queer, Mysterious Symbol in Green Carnations

Tara Isabella Burton on One of Literature’s Great Trendsetters

In London in 1892, everybody—or, at least, everybody who was anybody—was talking about one thing: green carnations. Nobody was sure, exactly, what wearing a green carnation meant, or why it had suddenly become such a deliciously scandalous, dazzlingly fashionable sartorial statement. All anybody knew was that one day, at a London theater, someone important (stories differed as to who exactly it was) wore a green carnation, or maybe it had been a blue one (stories differed about that too).

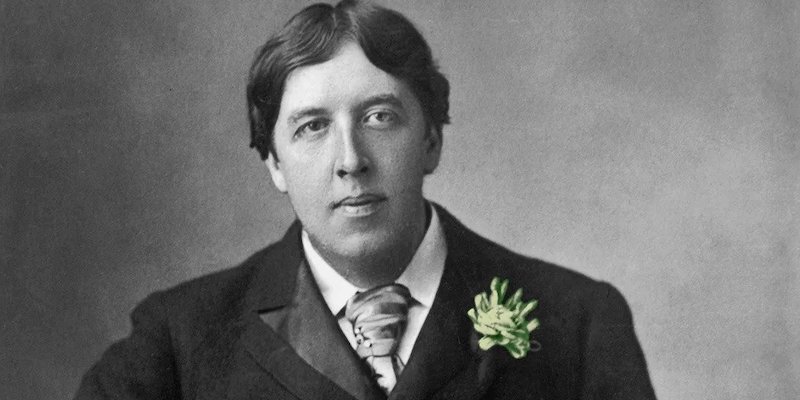

Green carnations may have had something to do with sexual deviance. They may also have had something to do with the worship of art. And the whole thing somehow had to do with Oscar Wilde, the flamboyant playwright, novelist, and fame-courting dandy who—as he never tired of telling the press—put his talent into his work but put his genius into his life. Wilde lived his life as a work of art (or let people think he did). The affair of the green carnation gives us a little glimpse into how.

One story about what exactly happened comes from the painter Cecil Robertson, who recounts his version in his memoirs. According to Robertson, Wilde was keen to drum up publicity for his latest play, Lady Windermere’s Fan. A character in the play, Cecil Graham—an elegant and witty dandy figure who rather resembled Wilde himself—was ostensibly going to wear a carnation onstage as part of his costume. And Wilde wanted life to resemble art.

“I want a good many men to wear them tomorrow,” Wilde allegedly told Robertson. “People will stare…and wonder. Then they will look round the house [theater] and see every here and there more and more little specks of mystic green”—a new and inexplicable fashion statement. And then, Wilde gleefully insisted, they would start to ask themselves that most vital of questions: “What on earth can it mean?”

Robertson evidently ventured to ask Wilde what, exactly, the green carnation did mean.

Wilde’s response? “Nothing whatsoever. But that is just what nobody will guess.”

It’s unclear how much of Robertson’s story is true. If any large group—including the actor playing Cecil Graham—wore green carnations at the Lady Windermere’s Fan premiere on February 20, nobody in the press commented upon it. That said, the author Henry James, who was in the audience that night, remembers Wilde himself—the “unspeakable one,” he called him—striding out for his curtain call wearing a carnation in “metallic blue.”

The green carnation is something desperately exciting, understood not by ordinary society women but by Brummell-style dandies, shimmering with hauteur.

Within days, carnations were everywhere. Just two weeks later, a newspaper covering the premiere of another play, this one by Théodore de Banville, reported a bizarre phenomenon: Wilde in the audience, surrounded by a “suite of young gentlemen all wearing the vivid dyed carnation which has superseded the lily and the sunflower,” two flowers that had previously been associated with Wilde and with fashionable, flamboyant, and sexually ambiguous young men more generally.

A little over a week after that, a London periodical published another piece on this mysterious carnation. It is a dialogue between Isabel, a young woman, and Billy, an even younger dandy—heavily implied to be gay—about the flower, which Billy has received as a gage d’amour (the French is tactfully untranslated) from a much older man. Billy shows off his flower to the curious Isabel with the attitude of studied nonchalance: “Oh, haven’t you seen them?…. Newest thing out. They water them with arsenic, you know, and it turns them green.”

The green carnation is something desperately exciting, understood not by ordinary society women but by Brummell-style dandies, shimmering with hauteur. It’s deliciously dangerous, perhaps even a tad wicked; the carnations are colored with poison, after all. It’s also, in every sense of the word, a little bit queer.

The green carnation’s appeal as a symbol of something esoteric persisted. Two years after the premiere of Lady Windermere’s Fan, an anonymous author—later revealed to be the London music critic Robert Hichens—published The Green Carnation, a novel that appears to be very obviously based on Oscar Wilde’s real- life homosexual relationship with the much younger Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas.

That relationship would prove to be Wilde’s downfall. In 1895, Wilde would be arrested on charges of “gross indecency” at the behest of Bosie’s influential father and spend two years imprisoned at Reading Gaol.

Wilde would emerge penniless and psychologically shaken, and he died in effective exile in Paris a few years later. Indeed, The Green Carnation, despite being a work of fiction that Wilde didn’t even write, would be presented at his trial as evidence of his moral and sexual degradation. The press, meanwhile, took Wilde’s own propensity for carnations “artificially colored green” as another admission of guilt. By then, it was allegedly common knowledge that such a flower was worn by “homosexuals in Paris.”

In The Green Carnation (the novel, that is) we see Oscar Wilde reimagined as the playwright Esmé Amarinth, the “high priest” of what we learn is the “cult of the green carnation.” Amarinth and his followers are all dandies. Their religion is a passionate worship of the artistic and the artificial, which they believe is superior to the meaningless, empty, and brutal world of nature. Like Rameau’s nephew before them, they are fascinated with originality and the way in which a soupçon of carefully chosen transgression can help them ascend the dull, natural plane and reach a higher, more divine form of existence.

Placing a green carnation into his buttonhole, one of Amarinth’s devotees, Reggie, muses how “the white flower of a blameless life was much too inartistic to have any attraction for him.” Rather, we learn, Reggie “worshipped the abnormal with all the passion of his impure and subtle youth.” Meanwhile, Amarinth predicts that the artificially green carnation will soon be replicated by nature.

Just as Wilde’s seemingly arbitrary decision to promote the green carnation had, within years, transformed the flower into a gay fashion symbol whose origins nobody could seem to remember, so, too—in Amarinth’s telling, at least—would reality change to fit the fantasy. “Nature will soon begin to imitate them,” Amarinth is fond of saying, “as she always imitates everything, being naturally uninventive.”

The Green Carnation is not a very good novel. Oscar Wilde, who was briefly accused of being its anonymous author, declared angrily that he most certainly had not written that “middle-class and mediocre book.” He had, of course, invented that “Magnificent Flower”—the arsenic-green carnation—but with the trash that “usurps its strangely beautiful name,” Wilde had “little to do.” “The Flower,” he concluded, is “a work of Art. The book is not.”

These dandies believed—or at least made out that they believed—that the highest calling a person could have was a careful cultivation of the self: of clothing, sure, and of hairstyle, but also of gesture, of personality.

Be that as it may, The Green Carnation, though it is certainly a satirical exaggeration, can tell us much about this strange, new class of young men cropping up not only in London but also in Paris, Copenhagen, and so many other European capitals during the nineteenth century: the dandy. Inheritors of the mantle of Beau Brummell but far more flamboyant in their affect—John Bull would certainly have turned around to look at them in the street—these modern dandies didn’t just live their lives artistically.

Rather, as Hichens’s novel suggest, they had discovered in their obsession with beauty and self-fashioning a new kind of religion, a worship of the unnatural and the artificial as a means of escaping from both the meaningless void of “nature” and the equally meaningless abyss that was modern life.

These dandies believed—or at least made out that they believed—that the highest calling a person could have was a careful cultivation of the self: of clothing, sure, and of hairstyle, but also of gesture, of personality. And behind that belief lay a kind of bitter nihilism, as poisonous as arsenic itself. Nothing meant anything, unless you decided it did. A green carnation could signify homosexual desire, or aesthetic dandyism, or “nothing whatsoever,” depending on your mood and what you felt like conveying to the world that morning.

Self-creation was possible, even desirable, even godlike, precisely because there was no meaning in the world without it. The world was nothing but raw, formless material for the clever and the enterprising to shape to their will. Truth was not objective, something out there in the ether. Rather, it was something for human beings to determine for themselves by shaping the impressions and responses of other people.

“Reggie was considered very clever by his friends,” we learn from Hichens, “but more clever by himself. He knew that he was great, and he said so often in Society. And Society smiled and murmured that it was a pose. Everything is a pose nowadays, especially genius.”

Vivian Grey’s “sneer for the world” had become something every dandy needed to possess.

______________________________

Excerpted from Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians by Tara Isabella Burton. Copyright © 2023. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Tara Isabella Burton

Tara Isabella Burton is a contributing editor at the American Interest, a columnist at Religion News Service, and the former staff religion reporter at Vox.com. She has written on religion and secularism for National Geographic, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and more, and holds a doctorate in theology from Oxford. She is also the author of the novel Social Creature (Doubleday, 2018).