Paul Laurence Dunbar, a prodigious black poet, and Orville Wright, a precocious white inventor, became entrepreneurial partners in a short-lived newspaper which circulated in Dayton, Ohio, called the Dayton Tattler. As classmates in Central High School, Paul and Orville respected each other as collaborators who could launch the periodical close to Christmastime in 1890.

In the back room of the Wright & Wright print shop—co-run by Orville and his brother Wilbur, and located on the second floor of a building on the corner of West Third and Williams Streets in West Dayton—Paul’s reported scrawl on a wall testified to their enduring bond, which would straddle the line between opportunistic partnership and genuine friendship:

Orville Wright is out of sight

In the printing business.

No other mind is half as brightAs his’n is.

Article continues after advertisement

As a teenager, Paul was refining his reading and writing of poems: these years comprised a period of personal struggle and self-inquiry; he grappled with his absentee father’s troubled legacy for him and the rest of his family, and he sought to articulate his memories and imaginings in his early fiction, poetry, and drama. Jim Crow racial segregation normally kept students, black and white, like him and Orville apart.

Yet they were “close friends,” Orville himself later reflected. “Paul Lawrence [sic] Dunbar, the negro poet, and I were close friends in our school days and in the years immediately following. . . . When he was eighteen and I nineteen, we published a five-column weekly paper for people of his race.” The improbable publication by two boys approaching adulthood—one black, the other white—of a periodical for the African American readers of Dayton was the remarkable backdrop to Paul’s transformation into a professional writer and Orville’s own into an iconic aviator.

*

A pivotal moment in Paul’s growth from prodigious to professional writer occurred in the late 1880s. At this time, he was being shaped not only by his education inside Central High School but also by the changes to public education in Dayton and in broader Ohio. By that time, the city’s gradual racial desegregation policies aligned with those of a little more than half of the cities in Ohio. Prior to 1887, Robert W. Steele, former president of the Dayton Board of Education, stated that, despite the slow pace of ending the racial segregation of public schools by legal means (in 1889), African American parents had the right, in the wake of the 1868 ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment (which accorded citizenship to African Americans and certified the rights of citizens to due process and equality before the law), to enroll their children in hitherto all-white schools. By his count, no parent did.

The improbable publication by two boys approaching adulthood—one black, the other white—of a periodical for the African American readers of Dayton was the remarkable backdrop to Paul’s transformation into a professional writer and Orville’s own into an iconic aviator.After 1887, racial segregation no longer affected Dayton public education. (The existence of only one high school in Dayton when Paul was enrolled obviated the need to segregate schools at that level.) Yet local school boards here and elsewhere in northern states exploited one last loophole: racially segregating classrooms within racially mixed schools so as to avoid displaying any open defiance of state law.

No evidence indicates that Paul, as he turned fifteen and entered the tenth grade a mere seven months after statewide desegregation, was at all separated from his classmates at Central High School. (In an official school photograph, he stands alongside the classmates of his initial cohort, the class of 1890, albeit he stands rather aloof.)

Paul and his Central High School classmates, with Orville Wright in center, back row, circa 1890.

All things considered, his memory of Central High School turned out to be favorable. He was the only African American in his class, yet fellow classmates still “were kind to him,” he stated later in life. He also befriended and collaborated with a young white man—the one in the rear, standing before the central doorway in the class photograph—whose own zeal for technological innovation would soon reach historic proportions.

*

When Paul first began the ninth grade in high school in fall 1886, he was scheduled to graduate four years later, by spring 1890. But he delayed his graduation by a year to pursue an extracurricular interest in newspapers.

Ohio was an especially fertile state for newspaper publication, which was in vogue during the last decade of the nineteenth century. Readers craved information, whether education or entertainment. As long-standing Dayton newspapers underwent mergers, rebranding, and political realignments during the nineteenth century, their African American readership remained small in number and fragile as a literate community. Paul continued to write poems but, mindful of these circumstances, anticipated the need to find places to publish them. The growth of periodicals throughout the country intrigued him.

In Orville, Paul discovered an ideal high school companion in print culture—in the writing and editing of pieces for newspapers, in the enterprise of printing and circulating them, and in the use of them as a vehicle for amplifying an original voice for the good of local readers. Orville had been ensconced in the world of newspapers while growing up. His father, Milton Wright, was an United Brethren Church clergyman and editor of the Religious Telescope, a periodical of the United Brethren Printing Establishment, from 1871 (the year Orville was born) to 1875. The Wright family was at the epicenter of the religious printing press, enhanced by Milton’s ascension to United Brethren Church spokesman as a result of his editorship.

By 1889, Orville decided that, more than school, he wanted to be in the printing business. On March 1, 1889, he began publishing the West Side News, one year after he had constructed a large press to handle complex or demanding newspaper jobs. Geared for the West Dayton community, the weekly paper ran for a mere thirteen months, but Orville remained committed to newspaper publishing. The motto of his next paper, the Evening Item, which appeared less than a month after its predecessor the West Side News, was that it would print “all the news of the world that most people care to read, and in such shape that people will have time to read it.” It would also cultivate “the clearest and most accurate possible understanding of what is happening in the world from day-to-day.”

If the Dayton Tattler showcased Paul’s entrepreneurial instincts and editorial expertise, it also revealed for the first time his complex stance on race.Despite its admirable mission, the Evening Item died even faster than the West Side News. Lasting only four months, the Evening Item closed down in August 1890, unable to hold its own among the Dayton competition, which included more than ten papers. But with the rebirth of the family printing business as “Wright & Wright,” Orville’s new operation could serve Dayton businesses seeking to publish directories, reports, programs, posters, advertising cards, and letterhead. The printing office moved a little more than a block away, from Hawthorn Street to the corner of Third and Williams Streets.

Within the crucible of the publishing world, Orville and Paul linked up at the outset of academic year 1890–1891. Paul was now a member of the class of 1891, given that he was considerably ill during large swaths of calendar year 1889, likely forcing him to take an academic leave of absence overlapping his original third and fourth years of high school. (He started the ninth grade in academic year 1886–1887, so now he would need five years, not four, to graduate.) As they approached the Christmas season of 1890, the white printer and the black editor looked forward to publishing a newspaper for local African American readers.

*

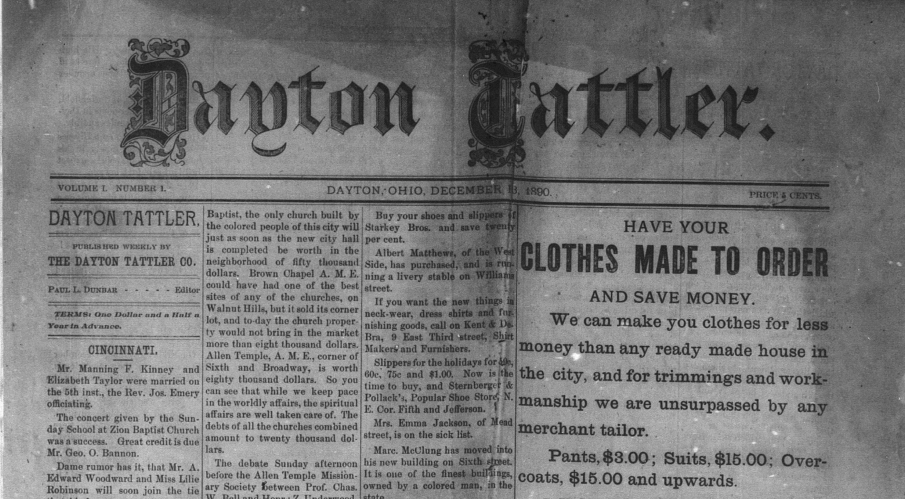

The Dayton Tattler debuted on December 13, 1890. The publishing house of Wright & Wright and the editorship of Dayton Tattler Co., which Paul founded to certify the Dayton Tattler as a commercial business, joined forces to produce what he thought would be the first of many issues of a weekly newspaper— each unfurling across four broadsheet pages in “bright and newsy” fashion, as he first gleefully said after the initial local reviews of the first issue came in. Paul rightly recognized that circulating the Tattler only on Saturdays enabled him to cast it as a weekend paper. By the turn of the century, the weekend was the most lucrative time a newspaper, especially those affiliated with dailies, could hit the stands. Paul was riding that wave.

First issue of Dayton Tattler (December 13, 1890)

The Tattler was the quintessential startup paper. Throughout its pages, readers encountered direct appeals for subscriptions, which in standard fashion offered a discount for longer periods. The newsstand price was 5¢ per issue; a one-year annual subscription, paid in advance, cost $1.50. Rates in the second issue of the Tattler offered a three-month subscription for 50¢ and a six-month subscription for 75¢. Plastered across the right side of the first page was an impressive slew of advertising from local businesses—merchant tailors and clothiers, a jeweler, a carpet cleaner, a furnisher, a grocer, restaurants and confectioners, a millinery, a cigar and tobacco house, an artisanal repairman, a pharmacy, a handyman, a shaving parlor. The paper had the feel of a publication mostly by, about, and for the local communities of Ohio.

Paul envisioned the Tattler as an informational bulwark against financial corruption in politics, as a means of rescuing “the hearts of our colored voters and snatch them from the brink of that yawning chasm—paid democracy.”The Dayton Tattler appealed to an audience within and beyond Dayton. In the first two issues, published on December 13 and 20, 1890, were lengthy columns about marriages, holiday festivities, and the Baptist and Methodist churches in Cincinnati. Stories about the strange and obscure were excerpted from other newspapers around the country. Along with brief essays on the likes of “Negro superstitions,” these stories showed Paul’s interest in delivering important news as well as light entertainment to African American readers.

If the Dayton Tattler showcased Paul’s entrepreneurial instincts and editorial expertise, it also revealed for the first time his complex stance on race. In an editorial he wrote for the first issue, he stated that the periodical above all catered to and sought to cultivate further an African American readership, which “has for a long time demanded a paper, representative of the energy and enterprise of our citizens.”

The Tattler had two mottos: “Gives all the news among the colored people” and “The Tattler should go into every family of our race in this state.” But its mission went beyond merely delivering the news; it sought to contribute to the economic, artistic, and political well-being of the race: “to encourage and assist the enterprises of the city, to give our young people a field in which to exercise their literary talents, to champion the cause of right, and to espouse the principles of honest republicanism.”

Just as remarkably, Paul envisioned the Tattler as an informational bulwark against financial corruption in politics, as a means of rescuing “the hearts of our colored voters and snatch them from the brink of that yawning chasm—paid democracy.” For the paper to survive and fulfill these goals, readers had to give back in at least one of three ways: pay for a subscription, pay to advertise in its pages, or submit a piece of writing.

Paul’s desire to enlighten and uplift “colored” readers superseded his desire to fill the Tattler with political opinions about race:

A great mistake that has been made by editors of the race is that they only discuss one question, the race problem. … We do not counsel you, debaters, writers, and fellow editors, to throw away your opinions on this all important question; on the contrary we deem it one worthy of constant thought. But the time has come when you should act your opinions out, rather than write them. Your cry is “we must agitate, we must agitate.” So you must but bear in mind that the agitation of deeds is tenfold more effectual than the agitation of words. For your own sake, and for the sake of Heaven and the race, stop saying, and go doing.

At 18, Paul still had little experience of the world, and his mostly peaceful encounters with whites in Dayton could partly explain his erasure of the “race problem” from the pages of theTattler. But a profoundly racial design motivated his editorial bluster: he wanted to educate his readers to vote with a mind immune to financial corruption, even as he sought to downplay the activism of the written word. He planned to create more space in the Tattler for “other things than this one question to talk about.” His collection of local and national news, of both serious and silly types, sought to do just that.

Orville, on the other hand, found value in the Tattler for his own scientific curiosity.Yet, Paul’s call for readers to “agitate” in public instead of in print affiliated the Dayton Tattler with a storied tradition of African American culture. The Dayton Tattler predated by a decade the Boston-based Colored American Magazine, whose editor, Walter W. Wallace, declared in the first issue (in 1900) that “American citizens of color have long realized that there exists no monthly magazine distinctively devoted to their interests and to the development of Afro-American art and literature.”

If it could last long enough, the Tattler could forge a new path: to give “all the news among the colored people” of Dayton, even while subordinating horrific news about race relations to humorous views about social relations. But even its appeal to potential African American writers to “give us a variety and cease feeding your weary readers on an unbroken diet of the race problem” was, in itself, a commentary on the rhetorical narrowness of racial politics in America.

Orville, on the other hand, found value in the Tattler for his own scientific curiosity. In the Tattler’s third and final issue on December 27, 1890, Paul saw fit to include a small essay, “Air Ship Soon to Fly.” Inventor E. J. Pennington had announced to the stockholders at a Chicago meeting of the Mount Carmel Aeronautic Navigation Company that “we will sail into Chicago in the first of our air ships.” Paul agreed with his printers, the Wright brothers, that a story about the potential “manufacture of ships for traveling in the air” was news fit to print in a “colored” newspaper. Despite being buried in an issue of a newspaper on the verge of death, this story was one of the earliest seeds of evidence that Orville and Wilbur were conceiving of innovating the airplane.

*

After the demise of the Tattler, Paul returned to Central High School. He completed his final semester there, in spring 1891, as an exceptional (although not officially an honors) student. Though he and Orville would go their separate ways, they nonetheless had discovered and enjoyed common ground across the so-called color line: not merely within high school classrooms, where the curriculum forced them to learn the same lessons, but outside them, where newspapers instilled a shared sense of fascination.

For Paul, the allure was literary. He was drawn to honing further his exceptional skills of editing and creative writing—the ones that in a few years would elevate his poetry to international prominence. For Orville, the attraction was managerial. As much as he wished to help advance the mission of the Dayton Tattler to provide “all the news among the colored people,” in the words of one motto, he also wanted more business for the burgeoning printing press that he and his brother Wilbur co-founded and that helped sharpen the organizational acumen they would bring to aviation in the new century.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Paul Laurence Dunbar: The Life and Times of a Caged Bird by Gene Andrew Jarrett. Copyright © 2022. Available from Princeton University Press.