How NOW Attempted to Exclude the Third Woman’s Alliance From Feminist History

Patricia Romney on the Women's Strike for Equality

and Racism Within Feminism

August 26, 1970, was, in many ways, a very ordinary summer day in New York City—warm but thankfully not too steamy. WMCA radio in New York rated Stevie Wonder’s hit song “Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours)” number one among its top forty. The Mets lost (nine to seven) to the Atlanta Braves. On television, All in the Family, starring Jean Stapleton as Archie Bunker’s “dingbat” wife, Edith, reigned supreme.

It was also the day that women came together in never-before-seen numbers to demonstrate their passionate commitment to equal rights.

Much of the affluent population of the city had retreated from the August heat to summer sojourns in the Catskills, the Poconos, the Hamptons, Fire Island, Sag Harbor, the Vineyard, and other exurban and rural destinations. Poor and working-class folk contented themselves with Orchard Beach and the open fire hydrants of the five boroughs.

Frances Beal awoke that morning with her mind fixed on the many things she had to do before going to the demonstration. It was a Wednesday and she had taken the day off from work. She got up, showered, and picked out her light brown curly Afro, hair that was both soft and nappy, as if paying joint homage to her Black father and her white Jewish mother. A 30-year-old divorced Black woman with two children, a full-time job, and more than full-time activism, she threw on a dress that was perhaps a bit too short then woke her daughters, Ann, eight, and Lisa, seven, and got them dressed.

Fran dropped the girls off at her mother’s and then headed over to the Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA) office on the second floor of the rectory at St. Peter’s Church in the Chelsea section of Manhattan to meet with other Alliance sisters and pick up their banner. They traveled together uptown to the demonstration, banner in hand.

*

What the women saw when they arrived at the demonstration astounded them. They were used to demonstrations of scores, hundreds, and maybe even a couple of thousand people. On this day, fifty thousand women filled the streets on and off Fifth Avenue, blocking the thoroughfares and filling the expanse of the avenue from curb to curb, completely overrunning the one lane the police had allocated for their march down Fifth Avenue.

On this day, fifty thousand women filled the streets on and off Fifth Avenue.

Women were everywhere—individuals, small groups, whole organizations had come out in unbelievable numbers in response to Betty Friedan’s call for a national strike to bring attention to the reality that despite 50 years of voting rights, women had not yet achieved full equality in the United States of America. In New York, the idea of a strike had evolved into a “march.” Thousands of women started parading down Fifth Avenue to Bryant Park, a 9.6-acre park adjacent to the main branch of the New York Public Library on Forty-Second Street and Fifth Avenue.

Contingents of women joined the march, holding up posters and banners that had not been fully visible while they convened on the side streets. Huge posters made of oak tag were stapled down the middle to two-by-fours. The ends of bedsheets were wrapped around wooden two-by-fours and stapled, forming enormous banners. All were emblazoned with words and pictures: the names of the women’s organizations, revolutionary slogans, caricatures, and women’s liberation symbols. As women joined the parade route, they raised their signs high or walked behind their handmade banners, proudly holding them steady and widespread as they marched. Thousands simply walked arm in arm, the words on their silk-screened T-shirts proclaiming their political views.

Radical feminists like the Redstockings and mainstream feminists like the National Organization for Women (NOW) were there, as were hundreds of groups representing all kinds of political viewpoints along the feminist continuum, their perspectives succinctly encapsulated on signs or on clothing. The political diversity was astounding. Friedan, the founder and president of NOW and the march’s organizer, carried a poster that read “Women Need Constitutional Equality N.O.W.” A sign on top of a car urged “Women Artists Unite.” The Working Women’s Contingent’s sign read “Child Care Centers for Working Mothers/Open All Jobs to Women/Equal Work, Equal Pay.” Another poster read “End Human Sacrifice, Don’t Get Married . . . Washing Diapers Is Not Fulfilling.” Acerbically, another read, “Oppressed Women. Don’t Cook Dinner. Starve a Rat Today.” Women protesting the war in Vietnam were there too, with signs that read, “Sisterhood Is Powerful—End the War,” “The Women of Vietnam Are Our Sisters,” “I’m No Breeder for Man’s War!”

In the midst of this bustle of activity, Fran and the handful of her Alliance sisters approached the march’s gathering point carrying their banner, with four simple words painted in the center in bold, black block letters: “HANDS OFF ANGELA DAVIS.” In the upper-left corner, they had painted the Alliance logo, the well-known symbol for “woman” distinguished by the addition of a power fist rising up from the base of the circle. The fist clutched a raised rifle that intersected the circle from left to right, with the barrel lifted up. Across the bottom of the banner in smaller letters were the name and address of the organization: Third World Women’s Alliance, 346 W. Twentieth Street, New York City.

As the women of the Alliance approached, Lucy Komisar, the parade coordinator and vice president of NOW, moved toward them. It was her job to check in all organizations and give them their places in the line of march. She looked at the Alliance women and at their banner and said, “The Angela Davis banner you are carrying has nothing to do with women’s liberation.” The Alliance women would not be allowed to march.

*

“It has everything to do with the women’s liberation we’re talking about,” Fran responded to the NOW parade coordinator’s assertion that the Alliance’s sign had nothing to do with women’s liberation. She did not relent. She insisted and persisted. Like the tree planted by the water in the old civil rights song, Fran would not be moved. The sisters of the Alliance did indeed march that day. Fran was stationed at the right corner of the banner, lifting it high with Affreekka Jefferson, Barbara Goff, Karen D. Taylor, Stella Holmes Hughes, and others.

I was 26 years old on that August day and I, too, marched down Fifth Avenue with the Alliance contingent. My compañero at that time, Joaquín Rosa, had told me there was to be a demonstration about women’s issues, and he’d encouraged me to go down to the march that afternoon. Joaquín and I were both activists in a community organizing group called Latin Action. I was nervous because I didn’t know anyone in the Alliance and really didn’t have a sense of what I was going to. Joaquín had stressed that the Alliance was an important organization, and for weeks, he had urged me to go. One problem was that I didn’t know any of the women, but there was something else too. Somehow, it felt like Joaquín was pressuring me to go, and that bred my resistance. I learned later in an interview with Lucas Daumont, former chairperson of Latin Action, that there had been an organizational directive for me and Zorina Costello, another Latin Action sister, to attend the demonstration.

The sisters of the Alliance did indeed march that day. Fran was stationed at the right corner of the banner, lifting it high.

This wasn’t unusual. Most movement organizations encouraged their members to participate in other organizations whose missions aligned with theirs. Latin Action’s agenda was the liberation of Latinos in the United States, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. The Alliance supported the liberation struggle of Latinos and other people of color around the world. Thus the politics and values of these two organizations were in alignment.

Overcoming my resistance, I met up with Zorina, and we went together. I was familiar with Fifth Avenue, having paraded down that street with my Mother Cabrini High School class-mates in four consecutive St. Patrick’s Day parades from 1958 through 1961, and again in 1963 when I was a student at the College of Our Lady of Good Counsel in White Plains, New York. This time the “uniforms” were different, and there were no “best school” marching trophies to be won. As I joined the sisters on the march down Fifth Avenue, I felt an immediate sense of solidarity and connection. I had experienced racism all my life as the only Black student in my classes from fourth grade through college. I’d had my own illegal abortion at age 22, performed by a nurse who put “a clamp” on my uterus and sent me home to endure 36 hours of labor until the embryo was expelled.

My parents had been working people in a household where two incomes were necessary. My brother was serving in Vietnam. I had been involved for several years in Latin Action, working to organize communities in the South Bronx, but, as a non-Latina, I was always a bit on the fringe. I fit easily into the definition of “third world” and for the first time did not have to explain myself any further. Energized by the other women and inspired by the speeches at Bryant Park, I realized by the end of that day that I would become a part of the Alliance. I had found my place in the movement.

The Alliance had a purpose in the march that day. They wanted to stand up for women’s rights, and they also wanted to emphasize a difference between the TWWA and the many white women’s organizations that marched. The Alliance banner expressed solidarity with the most well-known Black woman activist of the time, Angela Davis, an avowed communist freedom fighter. The words on the banner were meant to focus onlookers on the Alliance’s solidarity with her. The crucial, though perhaps less obvious, subtext was the message that the Alliance’s mission was the same as Angela’s: to wage an ongoing struggle against racism, sexism, and class oppression.

_______________________________________

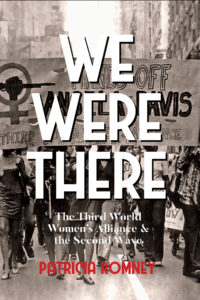

This excerpt is adapted from We Were There by Patricia Romney. Copyright © 2021 by Patricia Romney. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Feminist Press.

Patricia Romney

Patricia Romney received her PhD in clinical psychology from the City University of New York. She is a retired professor who taught at Hampshire College and Mount Holyoke College, and is the coeditor of Understanding Power: An Imperative for Human Services. She is based in Amherst, MA.