How Novelist Lynne Reid Banks Helped Me See Myself—and the World

Aaron Hicklin: “I yearned for a bigger life and was sure it would come for me.”

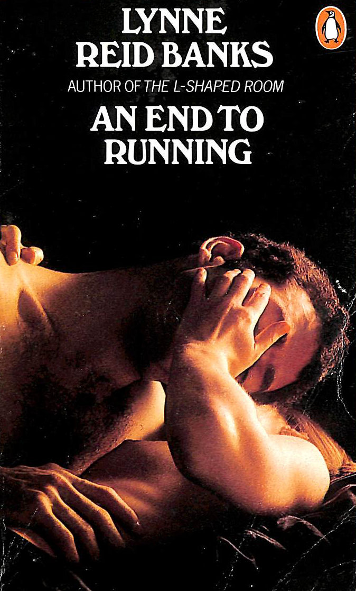

The breast was soft and supple like a blancmange, silhouetted against the hairy chest that pressed gently against it.

It was the chest, not the breast, that drew my attention. I was maybe 15, and it was the 1980s, when naked people were still a rare commodity. I had seen them, of course, in the locker rooms, and in a faded copy of Playboy that I found under my parents bed, and I’d spent too much time examining my own body for signs of what in sex ed class we were taught to call pubescence. For me, more than for my friends—as I discovered in the showers—it was going to be a long road.

I wasn’t expecting to find a naked man at the school book fair. But there he was. A naked Jewish man, too. A naked Jewish man called Aaron, apparently having sex on the cover of Lynne Reid Banks 1966 novel, An End to Running, having somehow slipped past the school censors. Maybe someone was feeling cheeky that day. We don’t see all of Aaron’s nakedness, of course, just enough to hint at what lies out of sight.

Swept up in the worldliness of Banks’ characters, I yearned for a bigger life and was sure it would come for me.

I bought the book, a bold and daring move for a kid as cautious as I was about being called out. But this naked man with the prominent clavicle and long, urgent fingers wasn’t just an object of teenage lust; he shared my name. What were the chances? I was 15 and had gone through life without meeting a single Aaron beyond the credits for Dynasty. But Aaron Spelling was impossibly distant, and not of my world. The magic of a novelist like Lynne Reid Banks was to make Aaron Franks feel as real to me as myself.

Here’s how Martha, the narrator of An End to Running, describes him when they first meet:

The eyes that met mine were sleepy; only a portion of the strange, pale irises was visible. They were set on either side of a strong, beaky nose under sharply winged eyebrows. His face was both bony and sensual; his mouth, Semitically full and yet somehow austere, was closed in a firm, almost cruel curve. His hair was black, silky, brushed forwards from the crown, cut to lie flat on his head like a little boy in the streets of Paris. His hands lay on the table on either side of the typewriter, palms pressed flat, but relaxed. He wore a blank, waiting expression; not one that might turn into laughter.

All these decades later, that description seems a little too ripe, a little too crowded with adjectives, though I still love the way Banks conjures a Parisian boy, silky hair brushed forward.

Aaron Franks was probably the first mature man I knew with any intimacy. That was the magic of a good novel, of course, and I neither realized nor cared that I was reading a romance novel marketed to women, and that it was doing to me what it was designed to do for women. I was smitten, although whether with Aaron Franks, or with an ideal of the man I wanted to be, or with a life I wanted to live, was hard to separate.

Banks is a persuasive writer and rereading An End to Running I found myself slipping easily into her story of a tempestuous love match and the forces that aim to thwart it. It’s also toe-curlingly clear why it appealed to a closeted teenage boy. Aaron is a stud, who possesses a “hard male strength,” and “always wore his clothes as if he were naked and alone.”

In time, Martha overcomes her initial resistance to that cruel, if Semitically full and yet somehow austere mouth, and becomes Aaron’s mistress—a word writers still used then—and follows him to Israel to live on a kibbutz, where he remains a tortured writer. They did not end happily ever after.

Excluding Agatha Christie, who did not write about sex, An End to Running was my first adult novel. Later I would feel some shame at not being the kind of person who stumbled on the Brontes or George Eliot as a young reader. But I ripped through all the Lynne Reid Banks novels I could find and followed An End to Running with The L-Shaped Room, about an unmarried and pregnant woman living in a London boarding house alongside a Jewish writer and a Black musician, with a pair of prostitutes in the basement. A minor scandal when it was published in 1960, it feels dated now, as do so many books that are celebrated as progressive in their time.

Did I consider it strange for a teenage boy to be reading romance novels? I did not. Swept up in the worldliness of Banks’ characters, I yearned for a bigger life and was sure it would come for me. I had spent childhood making elaborate plans to run away—escapades that were soon aborted, though once I hitched a ride 12 miles to the nearest town and snuck on a train to London, avoiding the ticket inspector by hiding in the bathroom.

Another time I made it to a barn with my best friend, Jeremy. We lay down in the straw but were soon cold and hungry, and ready for a warm bed again. These flights from home weren’t protests against my parents; I was just feverish with a desire for adventure.

Then I did what every woman who ever lived in a Lynne Reid Banks novel has done, and ran away at 17 to live on a kibbutz. It’s only now that I see how happenstance and chance set the wheels of life turning. I wanted to find my Aaron Franks, or be Aaron Franks, or both. At the goodbye party that I organized in the village hall, I met a bearded young man from the neighboring village who took me outside and seduced me in the churchyard. The stubble prickled my face in shocks of pleasure. I realized that I quite liked hard male strength. We arranged a rendezvous for the next day, and I showed up groggy and hungover to find myself jilted for the first time.

My nostalgia for the past is insidious and inescapable. In some ways I am always the young guest in my idol’s home.

Like the disillusioned Aaron Franks in An End to Running, I eventually returned to England, and continued to read Lynne Reid Banks. We began a correspondence. By then she was done with writing about Israel, and had moved on to children’s books, encouraged by the success of The Indian in the Cupboard. “Perhaps I shan’t ever write another novel about Israel,” she wrote to me. “I really feel so much pain about it, I can’t do the necessary standing back.”

*

One summer weekend in the late 1980s, a glorious day when England looks and feels as it does in an Ivory Merchant film, all softness and dappled light, I took a train to Dorset, where Lynne Reid Banks was living with her husband on an old farmhouse surrounded by fields and sky. We had lunch. I jumped in their pool, alert to my youth in front of this elderly couple as I did laps back and forth. I had a sense of myself as others might see me, young and virile and swimming into my future, a less tortured Aaron Franks.

On that visit I brought with me a first edition of Children at the Gate, set during the Six Day War and published in 1968. Reading it you can hear Banks beginning to question where Israel was heading, the trap it was setting for itself through conquest and occupation. It was Banks, a news journalist before she was a novelist, who made me see most clearly that Israel had become an apartheid state, and that it would only get worse.

That afternoon in Dorset, I’d cut my thumb on a thumb tack while grabbing for a copy of Children at the Gate on the floor of a used bookstore dusty with neglect. I’d arrived at the farmhouse sporting a band-aid, but triumphantly thrusting forth my find, a first edition. On the title page, Banks wrote, “For Aaron, who spilt blood for this book.”

Now when I look at the book and see that signature and read that message I am taken back to that gauzy English afternoon, to the kindness of an author who didn’t have to take such an interest in a callow young man. My nostalgia for the past is insidious and inescapable. In some ways I am always the young guest in my idol’s home.

Banks was still living when I started retrieving these fragmented memories. On Friday I awoke to the news that she had died, aged 94. Earlier this year I’d found her writer’s portal online and wrote her a letter in which I recalled my afternoon at her Dorset farmhouse, swimming in the pool. Would she perhaps consent to an interview? She wrote back shortly afterwards to say she would, adding that since her hearing was going, an email exchange would work best:

Please remember I’m 95 in July and my hearing is pretty ropey, and I sometimes get a little muddled, especially with memories… FYI, my 49th book, The Red Red Dragon was published in hardback at the end of ’22 and comes out in paperback this August. I’m excited.

Is there anything more encouraging than a writer at the age of 94 looking forward to publication day?

That was the last I heard from Lynne Reid Banks. I’d left it too late. But I took a small measure of solace from having told her how much her work had meant to me. A writer should know how they’ve touched and shaped a reader’s life.

Aaron Hicklin

Aaron Hicklin has been editor of three magazines in the U.S.: BlackBook (2003-2006), Out (2006-2018), and Document Journal. He is the author of Boy Soldiers and The Revolution Will Be Accessorized (Harper Collins) a collection of writing that appeared in BlackBook. He has written for The New York Times, The Guardian, and the Wall Street Journal, among other publications. In 2015 he opened One Grand Books, a bookstore curated by celebrated bibliophiles, in Narrowsburg, NY; in 2015, he founded Deep Water Literary Fest in 2018, held each June in Narrowsburg.